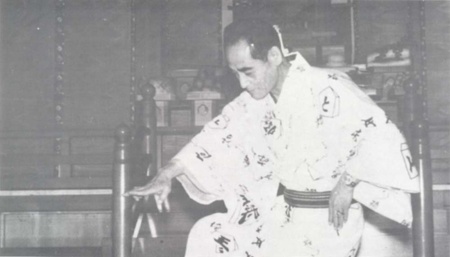

My grandfather, Masashi Bancho Okazaki, a Tenrikyo minister, had been separated from the family because of his occupation as a minister. He was reunited with my grandma and her five children in Crystal City in 1944. Their 9-year old daughter Sumi died in Crystal City of a brain tumor. In 1945, the family headed to the East Coast and went to work at Seabrook Farms, the frozen food factory in New Jersey. In 1946, the family finally found their way back to Boyle Heights.

Because of the housing shortage, the Okazaki family shared a house with the Fujii family on Fourth Street. My mom’s family slept on one floor, while the Fujiis took another floor. Mr. Fujii was also a Tenrikyo minister and had been together with our family in Crystal City. In 1953, the Okazakis relocated to a church on Fratkin Place, and remained there until it was demolished to build the Pomona Freeway. In 1957, the family relocated once again to Chicago Street in Boyle Heights, where they continue living to this day.

In addition to his duty as a minister, my grandfather was an artist. Papa (as my mom refers to him) enjoyed singing, painting, and doing traditional Japanese dancing. He was able to put his creative talents to work by handpainting custom neckties. He had other odd jobs, and worked as a gardener with Mr. Fujii while reestablishing the church after the war.

My grandma, Hideko Okazaki, found work in a garment factory doing piece work. My grandma complained that the Japanese women were assigned the more intricate items, which took longer to sew. The women who took the easier pieces were able to complete more items, and thus received higher pay.

My mom’s siblings, Kumi, Taka, and Fumio resumed their schooling. Mom started 2nd grade at First Street School. She and her older siblings went on to Robert Louis Stevenson Junior High School and all graduated from Roosevelt High School in the early-’50s.

* * * * *

My dad Walt, aka Mino, and his family were interned at Gila River Relocation Center. Returning to Los Angeles, the Kuidas were unable to return to their cantaloupe, lettuce, and cabbage farm in the San Fernando Valley where they had lived prior to the war.

With no place to go, they stayed at Koyasan Buddhist Temple on First Street for a few weeks. They moved into a fourplex with the Mihara family on Jefferson and Central, close to USC. As a 9th grade student, Dad went to George Washington Carver Jr. High School for six months. My grandfather, Keiichi Kuida, worked as a gardener with Mr. Mihara.

From there, the Kuidas went back to Canoga Park, and lived in the back house of an Italian farmer, just across the street from what is now the Topanga Plaza shopping center. According to my Grandma Kuida, after a year or so, the Italian boss wanted the family out of his house.

So in 1948, the family moved to Fourth Avenue near Crenshaw and moved in with cousins, the Iwanagas. At this time, Dad was in the 11th grade at Los Angeles High School, but felt that the school was too restrictive. Only seniors were allowed to wear white corduroys, which he was accustomed to wearing at the time. After a semester, Dad decided to go back to Canoga High, and got a job as a “school boy.”

Dad lived with the Bliss family in Tarzana and recalls that Ted Bliss was the producer of the Ozzie & Harriet Show. Dad took care of the gardening and the dishes and received free room and board in exchange. He went home on the weekends, but was able to finish his education at Canoga Park High School in 1949. I asked my dad how he was able to go back and forth from the Valley to Los Angeles, and he told me that he bought his first car, a ’31 Model A Ford in high school. By his senior year, he was on his second car, a ’36 Ford—the first in a series of cars for Dad.

At the same time, my grandfather was working as a gardener in Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, and other parts of Los Angeles. In addition, my grandma Kumae, worked as a seamstress in downtown Los Angeles, taking the Jefferson bus, until her retirement. In 1949, the Kuidas were able to save up for the down payment on a house, a few blocks from the Fourth Avenue house. My Auntie Keiko and Uncle Shag both graduated from Dorsey in the ’50s.

It’s somewhat reassuring to me that both of the homes purchased by the Okazakis and Kuidas during their resettlement period are still occupied by members of my family, who continue to live in Boyle Heights and in the Crenshaw District of Los Angeles. It keeps me close to my Issei grandparents, all of whom I often visit at Evergreen Cemetery, where many other Japanese Americans who lived through incarceration and resettlement in Los Angeles are buried.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices, Resettlement Years 1945-1955 in 1998. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 1998 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California