These books by Ellen Wu and Kristin Hass both assess a contested facet of Japanese American studies from a comparative perspective; and both are judiciously conceptualized, skillfully organized, soundly argued, lucidly written, and bountifully documented.

Fortuitously, their chronological spans (Wu, 1940s–1960s; Hass, 1982–2004) are sufficiently contiguous to warrant reviewing them jointly. Moreover, by jettisoning their non-Japanese American sections (in Wu, the Chinese American model minority experience; in Hass, three of the four war memorials built in the past three decades on the National Mall in Washington), this review can concentrate on connecting Wu’s analysis of the Japanese American model minority image with Hass’s evaluation of the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism during World War II.

When queried as to her book’s most significant contribution, Wu responded that it showed how the conception of U.S. Asians as model minorities (educated, prosperous, moral, lawful, and nationalistic) “is an invented fiction rather than timeless truth…[that] certain Asian American spokespersons, government officials, social scientists, journalists and others conjured up…for various political purposes.”

As regards this stereotype’s Nikkei variant, Wu spotlights the activity of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) leadership and its late moving spirit Mike Masaoka (1915–1991). She contends that during and following World War II they forged a governing political-cultural paradigm in which the Nisei soldier became Japanese America’s face and martial patriotism its default setting.

From its 1929 start JACL was an exclusive organization. Open only to Nisei, its leaders were primarily older, university-educated, middle-class businesspeople. The JACL leadership’s political conservatism and deference to white Americans repelled intellectuals, liberals, and progressives. Also, the JACL’s flag-waving alienated Issei and Kibei-Nisei by its flag-waving Americanism, as exemplified in its August 1941 executive secretary appointment of Mike Masaoka, a nationalistic Mormon Nisei from Utah.

In 1940, Masaoka orated his chauvinistic “Japanese American Creed” before the U.S. Senate, pledging to actively assume his citizen obligations “cheerfully and without any reservations whatsoever [emphasis added], in the hope that I may become a better American in a greater America.” Clearly, says Wu, Masaoka aimed this creed “at white opinion makers, legislators, and dignitaries.”

Prior to U.S. entry into World War II, the JACL organized the Southern California Coordinating Committee for Defense. Chaired by Mike Masaoka’s brother Joe Grant, it gathered information on subversive activities within the Nikkei community for Naval Intelligence. After Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack, the Los Angeles JACL chapter established the Anti-Axis Committee to expand SCCD’s work. Its roundup of Issei community leaders and their incarceration in alien internment camps rendered JACL largely anathema to the Nikkei majority.

Nonetheless, even before President Franklin Roosevelt’s February 19, 1942, signing of Executive Order 9006, JACL had convinced the U.S. government to grant it the power to represent all Japanese Americans. After 110,000 plus West Coast Nikkei were confined in 10 interior concentration camps, War Relocation Authority (WRA) administrators rewarded JACL for assisting in their community’s mass exclusion and imprisonment. But, observes Wu, “the popular perception that JACL leaders had acted as inu (dogs or stool pigeons) in their vigorous push to promote Nisei loyalty destroyed their credibility among other Nikkei.” Thus, suspected JACL camp “collaborators” were beaten and/or driven into exile, while the organization’s reputation and membership plummeted.

In April 1942, JACL spokesperson Masaoka presented authorities with recommendations for detaining Japanese Americans. Uppermost was having military service for Nisei, which the government had terminated, promptly reactivated. Meanwhile, camp JACLers pushed military service for Nisei to halt suspicion about their American loyalty, even though this exacerbated the League’s toxic unpopularity.

In November 1942, JACL convened an emergency Salt Lake City meeting of delegates from all 10 WRA camps. They voted “to ask the War Department to reclassify Nisei ‘on the same basis as all other Americans.’” This decision precipitated a bloody riot at the eastern California Manzanar camp in early December 1942. Coupled with the preceding November 1942 strike at Arizona’s Poston camp (likewise triggered by a JACL leader’s beating) the Manzanar Riot persuaded authorities to devise a mechanism for segregating “loyal” Japanese Americans from “disloyal” ones, an action for which JACL and Mike Masaoka had long lobbied.

In January 1943, Secretary of War Henry Stimson announced plans to form an all-Japanese American Combat team of mainland U.S. and Hawai‘i volunteers. The JACL endorsed this “Jap Crow” regiment for pragmatic reasons, and Mike Masaoka became its first volunteer. The next month a loyalty questionnaire was given adult camp inmates. Questions 27 and 28 proved controversial: “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attacks by foreign or domestic forces?” Those affirming these “registration” questions were recruited by the army (while negative respondents were remanded to northern California’s Tule Lake Segregation Center). However, only 1,181 camp volunteers, far short of the 3,000 anticipated, materialized. Many more volunteered from Hawai‘i, since there Nikkei had not suffered mass removal and imprisonment. These volunteers constituted the core of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which fought in Italy, France, and Germany, while compiling what historian Paul Spickard portrays as “a record of heroism unparalleled in the history of American warfare.”

The Nisei soldiers’ performance jump-started a villainous to valorous reversal in the standing of JACL and Masaoka within the Nikkei community. As the 442nd’s public relations officer, Masaoka cranked out some twenty-seven hundred stories stressing how Nisei soldiers had volunteered because they were Americans who deeply believed in democracy, “even though [their]…families were in detention camps as the result of a wartime aberration.” This public relations campaign, opines historian Alice Yang Murray, “helped conceal from mainstream America the history of protest against the government and JACL.” On the home front, the same message was sounded to Nikkei in and out of camp by JACL’s Pacific Citizen house organ and reverberated in JACL-oriented camp newspapers and free-zone vernaculars.

In January 1944, the War Department announced the military draft’s reopening to Nisei. Although applauded by JACL and Masaoka and accorded a surprisingly favorable camp Nisei reception, this action provoked draft resistance from roughly 300 Nisei inmates. JACL joined WRA and the U.S. government in castigating draft resisters as draft “dodgers” motivated by cowardice and/or pro-Japanism. As for the 85 draft resisters at Wyoming’s Heart Mountain camp, the JACL-led Heart Mountain Sentinel denigrated their constitutional rationale as a rationalization for ducking a fundamental duty of U.S. citizenship. When resisters were convicted for draft evasion and they, along with their Fair Play Committee leaders, were railroaded into federal prisons, the Sentinel deemed this scenario as justice duly served.

After the war, JACL hastened its institutional rehabilitation, mostly among resettled Nikkei populations living in marginal neighborhoods of interior urban meccas. According to Alice Yang Murray, JACL strongly desired to distance itself from draft resisters (as well as resisters within the military), while a few hard liners wanted JACL to urge the government “to deport immediately” those who failed to express loyalty” and to require the No-No population at Tule Lake Segregation Center to carry special identification cards. Instead, JACL decided to conduct a media blitz so exclusively focused upon the Nisei soldiers as to “erase the history of…resistance from public memory by denying its existence.”

This tactic enjoyed success for several postwar decades, thanks to JACL public relations efforts like sponsoring heroic Nisei airman Ben Kuroki on a national speaking tour, arranging for Arlington National Cemetery reburial ceremonies for Nisei soldiers, lobbying the army to name a troop transport after posthumously designated Nisei Medal of Honor recipient Sadao Munemori, and collaborating in the 1951 feature film Go for Broke! To quote Wu, the moral of this movie, for which Masaoka was a special consultant, “echoed JACL’s tale on martial patriotism: that Nisei had proved beyond a doubt their Americanism through their ‘baptism of blood.’”

By this time the JACL had solidified its hegemonic status as Japanese America’s spokesperson organization. Through its Masaoka-headed, Washington, DC-based Anti-Discrimination Committee, the League undertook a conciliatory, assimilationist-oriented drive to achieve its legislative and judicial goals (e.g., Evacuations Claims bill, Issei citizenship, and equal treatment before the law). Deftly exploiting the Nisei soldier to promote these actions, Masaoka was feted by the mainstream and JACL-controlled media as a “lobbyist extraordinary.”

As the 1960s–1970s social movements unfolded, however, JACL found its power to shape Japanese American identity and citizenship severely contested by activist Nikkei. They took exception to books like JACLer leader Bill Hosokawa’s Nisei: Quiet Americans (1969). A Denver Post editor and a Pacific Citizen columnist, Hosokawa was virtually silent about Nikkei individuals and groups who fought for social justice and democratic rights. In contrast, Hosokawa’s critics honored them, cheering books by historians like Roger Daniels’ Concentration Camps USA (1971) and Michi Nishiura Weglyn’s Years of Infamy (1976). Daniels questioned “the [JACL-WRA] stereotype of the Japanese American victim of World War II who met his fate with stoic resignation and responded only with superpatriotism,” while Weglyn, writing as “an outraged victim,” copiously and empathetically covered all WRA camp resisters and dedicated her book to civil rights lawyer Wayne M. Collins who had spent years restoring U.S. citizenship to some five thousand Tule Lake renunciants.

Although dissenting progressives within selected JACL chapters ignited the 1970s–1980s redress/reparations movement, the JACL Old Guard only grudgingly came to endorse it. In respect to the cultural style of the major redress organizations, the JACL comported itself the most closely to the model minority archetype, including greater emphasis upon martial patriotism. On August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan, a conservative Republican, signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. That he did so owed much to JACL’s Sansei strategy chair, Grant Ujifusa, arranging to have the president reminded of his impassioned December 1945 speech in Santa Ana, California. On that occasion, as Captain Reagan, a Democratic liberal, he had first saluted the family of Sgt. Kasuo Masuda of the 442nd―“a true American” who earlier that day had been posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his Italian battlefield heroics―and then effused: “Blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all one color. America stands unique in the world, the only country not founded on race, but in a way an ideal.”

Once redress was law, martial patriotic politics a la Mike Masaoka presented a more daunting challenge for JACL to perform. What during the redress movement had been muffled discontent by Nikkei toward the JACL’s and Masaoka’s wartime betrayal of their community, now became full-throated condemnation. When in 1987 Masaoka, assisted by Hosokawa, published the “saga” of Masaoka’s life and career “as a soldier, civil rights leader, and premier Washington lobbyist” in They Call Me Moses Masaoka, the book was pilloried by Masaoka’s critics. James Omura, the JACL’s number one enemy from 1934 throughout the war and slightly after it, was encouraged by younger Asian American supporters and Michi Weglyn to review it, which he did in 1989 for The Rafu Shimpo. Omura’s opening salvo presaged what would follow: “History indeed is infinitely the poorer and literature thereby greatly diminished by the publication of this fabricated account of the historic Japanese American episode of World War II.” This review’s damage was compounded by Deborah Lim’s finding in her 1990 JACL-commissioned report that, at the JACL’s March 1942 Emergency Meeting in San Francisco, Masaoka allegedly had recommended that “Japanese be branded and stamped and put under the supervision of the Federal government.”

The upshot of such mortal blows to the reputation of a dying Masaoka and the organization so closely identified with him, was that the JACL leadership largely treated Omura’s review with contemptuous silence and sought, unsuccessfully, to suppress Lim’s report. But these criticisms and others raised by Nikkei created a chorus of voices demanding that JACL emulate the U.S. government’s precedent by apologizing to Japanese Americans for the wartime misdeeds its leaders perpetrated against their community. Most specifically, this demand took shape in the necessity for JACL to express regret for their egregious maltreatment of the draft resisters who, as “resisters of conscience,” had chosen to exercise their American patriotism through clarifying and reclaiming their constitutional rights as U.S. citizens rather than robotically submitting to military service from behind barbed wire.

It is here that Kristin Hass’s book becomes relevant. Her concern is with the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism during World War II. Through the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation (NJAMF), this memorial’s development underwent discussions about its mission statement, site, design, and inscriptions. Only the last item was debated, and then with but a single inscription. There were quotations from California Nisei Congressmen Norman Mineta (Mike Masaoka’s brother-in-law), a child incarceree at Heart Mountain, and Sansei Robert Matsui, detained as a child at Tule Lake; Hawai‘i Nisei Senators Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga, both 442nd Regimental Combat Team veterans; WWII President Harry Truman; as well as two poems, a tanka and a haiku, by unnamed authors. Of these items, only the tanka poem (penned by Bill Hosokawa) was deleted, owing to its meaning being deemed too elusive.

In Hass’s words, the white heat of the debate “focused squarely on a [1940] quotation [by Mike Masaoka] celebrating the unquestioning loyalty of some Japanese Americans as a ‘creed’ shared by all Americans.” It declared: “I am proud that I am an American of Japanese heritage. I believe in her institutions, ideals and traditions. I glory in her heritage; I boast of her history; I trust in her future.” Both supporters and detractors of the controversial Masaoka on the NJAMF Board agreed to remove the “Japanese American Creed” title for the quote. But this did not resolve the controversy. Three board members, including San Francisco State oral historian Rita Takahashi, wanted the quotation deleted to avoid a perennial “fiasco,” and they formed the Japanese American Voice group to encourage the public to protest its inclusion to the National Park Service. Despite some seven hundred protest letters pouring into the NPS, the NJAMF Board’s prevailing majority “was not willing to let Masaoka go.” One Sansei graduate history student at Stanford, Steve Yoda, complained that Masaoka’s “blindly patriotic oath fans the model minority myth,” while Asian American scholar Larry Hashima fretted that Masaoka’s quote “may easily be interpreted to equate acquiescence and capitulation as the benchmark for patriotism.” In Hass’s opinion, Hashima was right, but his logic did not succeed in removing the “Creed” from the monument. Concluded a disheartened Hass: “It is there on the Mall for perpetuity.”

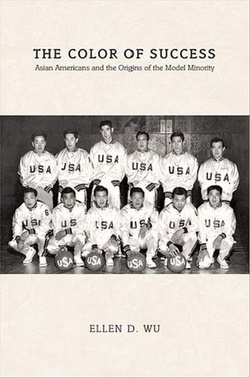

THE COLOR OF SUCCESS: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority

By Ellen D. Wu

(Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014, 376 pp., $39.50, hard cover)

SACRIFICING SOLIDERS ON THE NATIONAL MALL

By Kristin Ann Hass

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, 262 pp., $70.00, hard cover, $29.95, paperback)

*This article was originally published on Nichi Bei Weekly, on January 1, 2015.

© 2015 Arthur A. Hansen / Nichi Bei Weekly