George Mioya Hishida was born in Fukushima, Japan, in 1896 to a Christian missionary father who was absent from the family for long periods of time. He had two brothers and two sisters, and after graduating high school in 1913, he immigrated through Seattle and then went to Los Angeles to join his oldest brother. The brothers then worked in Salt Lake City, Utah, where his brother worked on the railroad and George worked as a sugar beet contractor and also in the spring and summer for the Southern Pacific Railroad as section hand. He also worked at the Garfield Smelter in Salt Lake City, Utah during the winter.

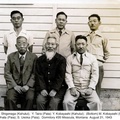

The brothers moved to Fresno in 1921, and George decided to make a career of a hobby he had developed in high school photography class. His George Photography Studio became successful and he decided to get married. He returned to Japan and went through a “bai-shaku-nin,” or matchmaker, and chose Shizuka Kanase, age 16, in 1923.

Shizuka had been born in Fresno, but moved to Japan as a child. As daughter Grayce says, “she had no choice [but to get married]. Even after the engagement they were not permitted to meet socially. They were virtually strangers.” The Hishidas had four children in Fresno before the war—son William Mineo in 1928, daughter Grayce Miyoko in 1932, son Shoji in 1937, and daughter Esther Taeko in 1938. After the war, daughter Crystal Kyoko was born in 1948. William had such a good time on a summer tour of Japan that he begged his parents to stay and study in Tokyo for a year, when he was 12. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, William was stuck in Japan, separated from his family.

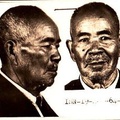

Daughter Grayce Nakamura says he was successful in photography and happy in his career. Unfortunately, the events of December 7, 1941 proved to be devastating for him and his family. Grayce recounts, “The FBI came to the studio and arrested Dad as a possible spy for Japan. They searched the studio for anything suspicious. Then they took him to our home where they went through photo albums and removed photos of his relatives and friends in Japanese Army uniforms. They took short wave radio, Japanese flags, and other items they thought were anti-U.S.”

An examination of Hishida’s file from the National Archives in College Park, MD reveals that a government informant reported that Hishida had “a small box of negatives placed under a shelf in such a manner as to indicate that they were being kept out of sight” and photographs of Japanese men in army uniforms, his brother-in-law who served in the US Army with machine guns in the photo, Friant Dam, the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges, and other locations that could be considered spying, as well as “microscopic negatives and pictures.” Hishida replied that the negatives and photos were left behind by customers and “admitted he had reduced negatives and pictures to fit lockets for customers.”

Grayce said, “My mom was told to be at a government office by 8 a.m. so we could say our goodbyes. When we arrived there we were told that he had already been transported to Northern California. I did not see my dad from March 1942 until July 1943 when he was paroled to my mom’s custody since she was an American citizen.

“My dad was sent from San Francisco to New Mexico. We heard from him but his letters were censored with blacked out sentences. We had my dad’s business friends, lawyers, and bankers write to the government vouching for my dad, but nothing happened.”

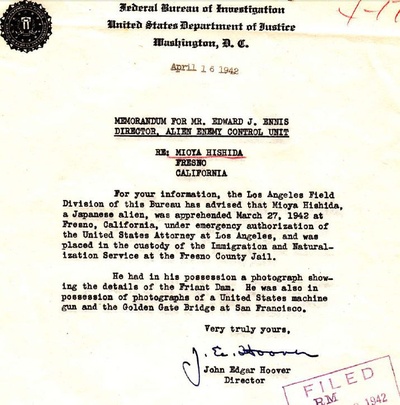

Hishida’s file includes a letter signed by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover advising the Alien Enemy Control Unit that Mioya Hishida had been apprehended on March 27, 1942 in Fresno and was placed in custody at the Fresno County Jail. It noted that “he had in his possession a photograph showing the details of the Friant Dam. He was also in possession of photographs of a United States machine gun and the Golden Gate Bridge at San Francisco.” The photo of the machine gun was actually in the same shot as a photo of Hishida’s brother-in-law in the U.S. Army.

On May 22, 1942, the Alien Enemy Hearing Board in San Francisco recommended unanimously that “the subject be interned.” Shizuka had written a letter requesting his release, but it was unsuccessful.

By that time, the rest of the Hishida family had orders to move to the Fresno Assembly Center at the Fresno County Fairgrounds. “Mom had to close the studio and remove the photography equipment. She was lucky to have her family to help her. She stored everything in her house. After moving to the fairgrounds taking only what we could carry we were settled in Barrack E-7. We were next sent to Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas. We settled in Block 44.”

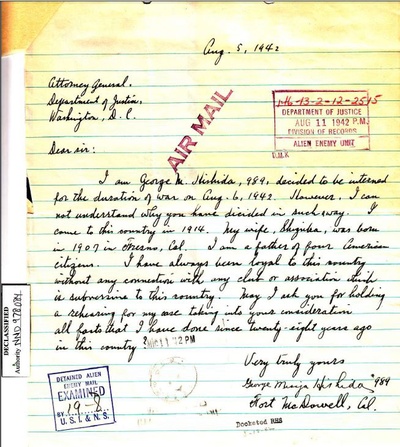

After George Hishida was sentenced to be interned, he was sent to Angel Island—the facilities on the island including the former Immigration Station were part of the military base Fort McDowell. While he was there, he sent a letter appealing his internment, which is copied below. It is one of the few letters from an Angel Island internee while he or she was detained there that we have found.

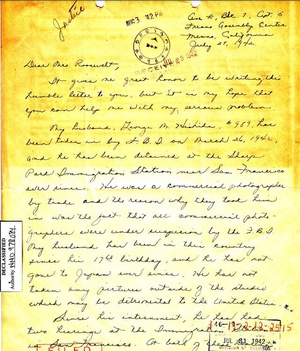

Shizuka wrote letters to the U.S. Attorney, Attorney General, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt requesting her husband’s release to join the family. On August 8, 1942, she wrote, “I am in a rather embarrassing position. I have a younger brother who is in the U.S. Armed Forces and yet, my husband is kept in a concentration camp. It doesn’t make sense does it? I am now living in the Fresno Assembly Center with my three small children, and I am in urgent need of his presence. I have been suffering from sickness [asthma] for many years, and I feel lost without my husband.”

Eleanor Roosevelt later wrote an article for Colliers where she said, “‘A Japanese is always a Japanese’ is an easily accepted phrase and it has taken hold quite naturally on the West Coast because of some reasonable or unreasonable fear back of it, but it leads nowhere and solves nothing. Japanese-Americans may be no more Japanese than a German-American is German… All of these people, including the Japanese-Americans, have men who are fighting today for the preservation of the democratic way of life and the ideas around which our nation was built.” Perhaps Shizuka’s letter had an impact on the First Lady.

Grayce later noted, “I tried talking to my dad about his life as a prisoner of the U.S. Government. I wanted to know. He said it was the worst time of his life and he did not want to talk about it. He wanted to forget that period. He did tell me that he was treated roughly. I think he said he was in solitary confinement for a period. He was considered uncooperative. I think he had a hard time because he had a hearing problem. Anyhow, that is all he would share with me about his time in prison.

After Angel Island, George Hishida was sent to Lordsburg and then Santa Fe, New Mexico in June of 1943.

Grayce noted, “I think my dad was returned to us in July 1943. He came to Jerome, Arkansas. It was great to be a complete family again. He was paroled to the custody of our mom.”

Later Shizuka suggested going to repatriate to Japan to rejoin William. George was against the move but Shizuka prevailed and applied for the family to transfer to Tule Lake Camp, which had been set up as a segregation camp for those wishing to repatriate and others deemed “disloyal” because of a poorly worded questionnaire. While there, George persuaded the director of the camp to allow him to set up a photography studio, and he was allowed to go to Fresno to pick up his equipment. Unfortunately, his extensive wartime photography collection was destroyed in a fire in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

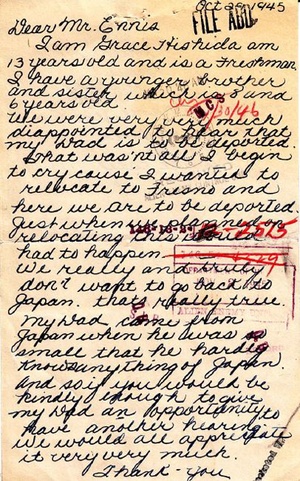

Sadly, in one of the last bombings in Tokyo in the summer of 1945, William and his uncle and aunt were killed. With the devastating news, the family requested that their application to repatriate be rescinded, but results were not immediate. Grayce (she added the “y” to her name later), now thirteen, wrote the letter shown to the right after the war was over but the family was still in Tule Lake. Her efforts were successful and the family was finally able to return home to Fresno in January of 1946.

The family had trouble getting the family who had rented their house in Fresno to move out, and eventually they finally were back home in June of 1946. George reopened his studio, and according to Grayce, his new hearing aid made his life so much better. “He was hearing everything for the first time. If he didn’t want to hear us, he shut the machine off.”

In 1952, Japanese were finally allowed to become naturalized citizens. “My dad studied the Constitution, learned the words to the Anthem, and whatever else was required to pass the test. Of course he passed. That was one of his proudest moments and we celebrated with him.”

Shizuka passed away in 1983, and “Dad was very sad and lonely. After Mom passed away, he said part of him died too.” George continued walking to work until his late 80s, finally retiring at age 91 or 92. He enjoyed his last years living with his widowed daughter Esther and her sons in Elk Grove. George passed away when he was 95½ in 1992.

Special thanks to Grayce Nakamura for her recollections and photographs and Adriana Marroquin for her research at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, MD. This project documenting Japanese internees on Angel Island is partially funded by the Japanese American Confinement Sites program of the National Park Service.

*This article was originally published by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation.

© 2015 Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation