Takeo Akizaki was one of nineteen men detained on Angel Island from August 5 to 7, 1942. This group was composed of men from Hawai`i, and according to Yasutaro Soga, all were U.S. citizens. Akizaki, who had also been detained on the island in March of that year on his way to Department of Justice camps, became a Shinto priest, and his beliefs were instrumental in his detention in these camps for most of the duration of World War II.

Between 1910 and 1940, Angel Island processed hundreds of thousands of immigrants, including many from Japan, and it was also a temporary detention center during World War II for close to 600 Japanese immigrants from Hawai`i and around 100 from the mainland, as well as American citizens like Takeo Akizaki. This is one of a series of stories about people of Japanese descent who were detained on Angel Island during World War II. For more information, visit AIISF’s Japanese American Internment on Angel Island page.

Some of those detained on Angel Island during World War II were American citizens by birth in the territory of Hawai`i. Even before Executive Order 9066 incarcerated over 110,000 West Coast Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants who could by law not become citizens, a number of these men were arrested by the F.B.I. and taken from their homes in both Hawai`i and the continental U.S. These men’s experiences are perhaps even less known than the Japanese-born who were considered “enemy aliens.” One was Takeo Akizaki.

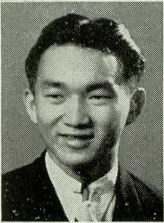

Takeo Akizaki was born in 1918 in the U.S. territory of Hawai`i, and therefore a U.S. citizen by birth. He graduated from McKinley High School and according to his yearbook entry, was McKinley Community Council vice president, J.S.A. president (perhaps this stood for Japanese Students Association?), and active in many activities including the McKinley ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Corps). Later, he took extension courses in theology from Temple Bar University and from the University of Chicago. He was arrested at the young age of 24 because of his work assisting his father in practicing the Shinto religion.

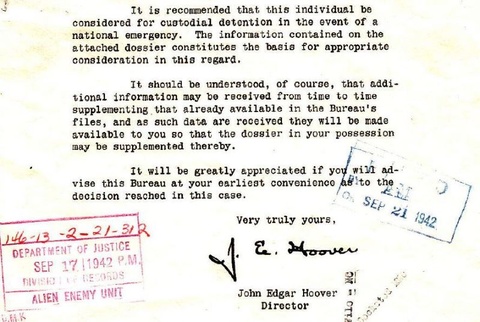

The file for Akizaki in the National Archives in College Park, MD, reveals that even before Pearl Harbor, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover recommended on December 5, 1941 that he be considered for custodial detention in the event of a national emergency. The FBI arrested him because he made one trip to Japan for the purpose of obtaining a commission as Shinto priest (when he was 14 years old!) and that “the subject’s religious sect considered to be anti-American and pro-Japanese under the influence of the Japanese Government. Two anonymous informants reported on what they perceived as Akizaki’s danger to America, including reports about Shinto rituals worshiping a fox god. Although the Internee Hearing Board reported that Akizaki was a citizen, hoped the U.S. will win the war, had no connection with espionage or sabotage activities, and he was licensed to perform marriage ceremonies as a Shinto priest, it doubted his credibility “by evasions and misrepresentations with reference to his functions as a priest, leaving the Board with serious doubts about the reliability of any of his own testimony.” Akizaki had been assisting his father in his Shinto practice, and also operated a small curio shop, according to his FBI file.

Clearly the board was looking for any excuse to intern Akizaki. Many Shinto priests were arrested by the FBI and interned for most of the war. The board, appointed by the Military Governor, made the recommendation that the subject be interned for the duration of the war, because it doubted his credibility.

Later in the war, after being released from internment, Takeo’s father Yoshio served as a minister for the famous 100th Battalion of U.S. soldiers from Hawai`i, which would later join the 442nd regimental combat unit and achieve great success and experience many casualties in the European theater. The elder Akizaki was mentioned in Israel Yost’s Combat Chaplain, which is about Yost's World War II experience as chaplain for the battalion.

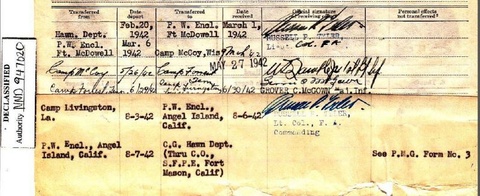

According to his record, Takeo Akizaki was held at the detention camp on Sand Island, near Honolulu, from January 6, 1942 to March 3, 1943, but other records show he was actually on the mainland between February and August of 1942. He was among the first group of internees that left Honolulu on February 20, 1942. National Archives records reveal that he was first detained on Angel Island from March 1 to 9, 1942, then sent to Camp McCoy in Wisconsin. On May 14, 1942, Akizaki wrote a letter requesting his release to Edward Ennis, Director of the Alien Enemy Control Unit of the Department of Justice, from his detention at Camp McCoy. This letter is in his file in the National Archives in College Park, MD.

Akizaki wrote, “It is my great honor, that I was born in the United States of America the doctrine of which, that is based on humanity and justice. I have been educated and trained in an American institution and college. My idea and ideology are entirely American and I have been endeavoring to do my utmost as a citizen of this country…My grandfather Gasuzaimon Akizaki came to Hawaii as a Japanese subject, but gave his life for the developments of industry in Hawaii…My father Yoshio, 44 years of age and my wife are the citizens of the U.S.A. by birth and are proud of their citizenship. I am therefore, the third generation in my family lineage since settled in Hawaii and I am proud of my citizenship.

“Unfortunately, I am now interned at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, with other Japanese subjects, although I have never betrayed or have done anything harmful to my country. Probably I am detained because due to my father’s profession as Shinto-Minister. However since 1937 he also devoted most of his time in retail Grocery business. I have no connection with my father’s occupation. It must have been some mistake that I was arrested and have been detained as a “dangerous subject.” I am just wondering how it could happen to a loyal citizen of whom I believe myself one…I never had Japanese training or had any relation or obligation whatsoever to Japan.”

Akizaki concluded, “My father Yoshio Akizaki had been arrested too, was broken down by the shock and lost the balance of his mind. But never has been restored to his wholesome health. Will it be not right for me to feel it my duty to go home and help my terrible suffering family.”

Akizaki’s pleas were ignored. From Camp McCoy, Akizaki was sent to Camp Forest, Tennessee on June 29, 1942 and then to Camp Livingston, Louisiana until August 3, 1942. Then on his way back to Hawai`i, he stayed on Angel Island from August 5-7, along with eighteen other men from that territory. Their names were all written on the barracks wall, according to Yasutaro Soga in his book Life Behind Barbed Wire.

After returning to Sand Island and being interned there until March 3, 1943, Akizaki was moved to the Honouliuli Internment Camp in western Oahu from March 4, 1943 until September 4, 1944. In November of 1943, Sergeant Heiji Fukuda of the 100th Infantry Battalion wrote a letter on behalf of his foster father Yoshio Akizaki and foster brother Takeo Akizaki, requesting their release from Honouliuli. Akizaki’s record showed that he was finally released from Honouliuli on September 4, 1944.

After the war, Takeo Akizaki became the Wakamiya Inari Shrine’s priest in 1951 following the death of his father Yoshio. The shrine had been constructed in 1914 under Rev. Yoshio Akizaki’s direction. Rev. Takeo Akizaki passed away in 1981, and the property where the shrine was located was sold and eventually the shrine became a part of the Waipahu Cultural Garden in Waipahu, Hawai`i.

Resources:

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD. Record Groups 60 and 389. Special thanks to researchers Adriana Marroquin and Gem Daus for their assistance in accessing these records.

Nomination Form: Wakamiya Inari Shrine. National Register of Historic Places. U.S. National Park Service. January 8, 1980. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

Soga, Yasutaro. Life Behind Barbed Wire. Honolulu, University of Hawai`i Press, 2008.

*This article was originally published by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation.

© 2015 Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation