30 years after her death, three artist friends of the Peruvian painter Tilsa Tsuchiya share their memories, full of endearing moments that reveal the character and sensitivity of an inspiring woman who was as selfless as she was passionate.

To talk about the work of Tilsa Tsuchiya (Supe, Barranca-Perú 1928) is to refer to eroticism, mythology, oriental philosophy, minimalist technique and the appearance of extraordinary beings. To talk about Tilsa Tsuchiya Castillo, and to do so with some of her closest friends, is to get to know the shy, sensitive and generous woman through a catalog of images that have been engraved in the memory of Venancio Shinki, Gerardo Chávez and Bruno Zeppilli.

Experiences, anecdotes and intimacies happen with surprising ease when these artists remember their fellow Fine Arts student, their supportive mentor and friend. Summarizing his life, from the years at the San Nicolás de Supe hacienda where he began to paint together with his brother, recounting his adventures as a student and defining the influence of his work is a biographical task done in books and documentaries to which are added these words like brushstrokes.

Adventure companions

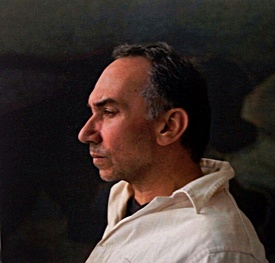

Gerardo Chávez is a Peruvian artist who needs no introduction. When he entered the National Higher School of Fine Arts in Lima in the mid-fifties, he did not need it either, since he immediately became one of the family, along with Tilsa Tsuchiya, Alfredo González Basurco, Alberto Quintanilla, José Milner Cajahuaringa , Oswaldo Sagástegui and Enrique Galdos.

(Photo: © APJ / Óscar Chambi)

“She was a very dear friend,” says Gerardo, who remembers that at first Tilsa had some technical difficulties in drawing that kept her away from her studies. “He worked for a time in his brothers' glass shop and left Fine Arts for a couple of years.” Already in 1956, when she returned to school, they met and joined a leftist movement, as well as a very happy and united group.

“There was great competition among the artists at school, we tried to be the best because there was a scholarship involved, but we helped each other. We lent each other the materials and celebrated falling in love in a seedy bar in the center of Lima that was on Amazonas Street,” recalls Gerardo, who seems to listen to the huayno that was played on the old radio in that place.

Talent, loves and Paris

In his apartment in San Isidro, Gerardo Chávez keeps two small sculptures of Tilsa among a large number of works of art, from paintings to the figure of an almost life-size horse. He bought them when Tilsa had already died and remembers that when she wanted to give him one of her paintings she told him “no China, better later.” A scene that was repeated because artists did not usually give works as gifts.

“In Fine Arts, Tilsa stood out in such a way that in the last year she was awarded the Great Gold Medal of the class of 1959. Her work had simple themes such as the emolientera or cats that seemed simple, but she did them with great sensitivity. . He looked different from the others. That personality always accompanied her.”

Chávez remembers that Tilsa said she had the love of her life: the sculptor Alberto Guzmán, although during those years of study she ended up falling in love with Alfredo González Basurco, with whom she later went to Paris thanks to the scholarship he received. “I went in their shadow, with the difficulty of not having money, and when we arrived in Europe I went to Florence. It was an adventure because we didn't know how to get back,” he says happily.

The student and the artist

(Photo: Personal archive)

Bruno Zeppilli was just 17 years old when he met Tilsa Tsuchiya. He remembers her sitting in a garden rocking chair, during lunch at the house of a mutual friend, Alfonso Castrillón. “He had perfect, straight hair and he was wearing dark glasses.” Many artists joined the field day in La Molina, but young Bruno was the one who caught the painter's attention.

Years later they would meet again when he and a group of art students visited her to ask her to donate some work for a benefit auction they were organizing. She welcomed them gladly, she was very interested in young people, says Bruno, and offered them a drawing. Bruno was pleased that she remembered him. “She had returned from Paris and was already a recognized artist; she had exhibited in Carlos Rodríguez Saavedra's gallery and received the Biennial Prize for Teknochemistry in 1970.”

One day, when Bruno was going to the Catholic University where he was studying Fine Arts, he saw Tilsa, who came to give a workshop. “He really liked plants, just like me, so I plucked some flowers from the garden for him. “Tilsa believed we were stealing because we did it secretly,” Bruno recalls with a smile. Since then he went to visit her at her house in Lima to water the plants and at the field house she had to the north, in Puente Piedra, which she called Shangri-lá.

Giving protector

When Tilsa received Bruno at home she used to be very dressed up, like for a date. That elegance was part of her conservative customs, as well as inviting him to eat at restaurants, but handing him her wallet so he could pay. “He said that you learn painting in cafes, by talking and observing what is behind the colors of the objects,” says Bruno, who for a time painted alongside him in the same workshop.

This experience and the friendship that went beyond painting (they played mahjong, a board game of Chinese origin) were due to the fact that Bruno did not treat her as a consecrated artist but as someone normal. Tilsa made him participate in her meetings, where he seemed to be her younger brother, and in some way she acted as his protector. She didn't want him to exhibit, she was worried that the market would affect her creative freedom.

“To paint you have to have something inside and Tilsa had it. It was very magical,” says Bruno Zeppilli, who for years frequented the artist's house daily. “He didn't drink alcohol and was never interested in making money.” Curiously, she is currently the most sought-after Peruvian painter. Last year, the Lima Art Museum auctioned one of his paintings for $150,000.

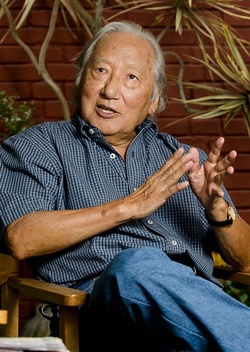

(Photo: © APJ Archive / Álvaro Uematsu)

Trusted friend

“When I saw her for the first time in the Fine Arts courtyard I thought she was crazy,” confesses Venancio Shinki, who was surprised that Tilsa Tsuchiya invited her teacher to have a few drinks at a cantina. He entered to study with the idea of being a portrait painter, but when he saw the paintings, the spiritual portraits of that Japanese girl who intrigued him from the first moment, he changed his mind.

He spent his afternoons contemplating, in wonder, Tilsa's work even when she was not in the workshop. When they became friends, Venancio would get to know that personal side of who is for him the greatest figure in Peruvian plastic arts. “She was very close to her friends and very modest with those she didn't know.” She became so close to the Tsuchiya family that one of her sisters was godmother to Shinki's first child.

It is curious that they did not meet in Supe, on the San Nicolás hacienda where they both grew up. Venancio never saw her because he did not study at the local Japanese school. One day, the painter told her that when Shinki gave her a painting to exhibit at the Havana Museum where she was going to exhibit, she had to interrupt her lunch because she needed to look at that painting. For him it was one of the best compliments he received.

influential artist

One of the greatest recognitions that Tilsa received came from the Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo. When he was in Lima, he said, after seeing one of his paintings, that the author was “a superb artist.” They later clarified that the author was a woman. “Tilsa is the only painter who has had an exhibition with a single painting,” says Venancio in reference to “Tristán and Isolde”, which was exhibited as a unique piece at the Ars Concentra gallery in Miraflores.

“We studied a lot and we had very good teachers who were brought together by Juan Manuel Ugarte Eléspuru,” comments the painter, who remembers the day he went to say goodbye to her in Callao, when he was leaving for Paris, and the time when upon his return he visited the Employee Hospital.

Tilsa was a heavy smoker, to the point that when Venancio Shinki entered her room he found her surrounded by friends, lying on the bed and smoking. “I couldn't handle his genius,” says Shinki, who emphasizes that just like smoking, he couldn't stop painting either. “He asked that they not knock on his door until twelve,” recalls the painter who, at 82, follows a routine similar to that of the most influential painter of his generation.

Letter from Sydney from the other Tilsa

Tilsa Guima's parents chose the name because they admired the Nikkei painter. In 2000, the Anthropology student was able to see Tsuchiya's work at the Lima Art Museum, gaining a greater appreciation for the name with which she was baptized and the stories she had heard about the artist. Some time later he prepared the essay The Red Warrior: Ethnic Identity in the Work of Tilsa Tsuchiya for the Ethnic Minorities course at the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos.

“For the essay I interviewed Frida Tsuchiya, her niece, in the house where Tilsa formerly lived. He described to me a very shy person, but extremely simple and noble. She told me that her father even supported her with the costs of her studies at the School of Fine Arts and that he became the harshest critic of Tilsa's work, but also a very dear person to her,” says Guima.

The father, Yoshigoro Tsuchiya, instilled art in both brothers (Wilfredo and Tilsa), to the point of making them paint together as children. Yoshigoro was a Japanese doctor who came to Peru to work at the San Nicolás hacienda. It was there where he met María Luisa Castillo, a young Peruvian woman of Chinese descent, daughter of the owner of the grocery store and who would be Tilsa's mother.

In his essay, Guima postulates that in Tilsa Tsuchiya's work there are the symbols of the three cultures to which she belonged: Peruvian, Chinese and Japanese. “She grows up and develops her career in this contrast, in a home in which there was a recognition and exchange of cultures, at a time when these groups maintained well-demarcated boundaries,” says Guima, who currently lives in Australia, where he did a master's degree in Cultural Studies.

José Watanabe: Tilsa, the blessed painter

Known is the admiration that the poet José Watanabe had towards Tilsa Tsuchiya, with whom he would form a close friendship. He would write about her in the prologue of the catalog* of the exhibition organized by the Telefónica Foundation at the Lima Art Museum:

One day, while I was painting and I was reading something, (Tilsa) said a disconcerting phrase:

-I think that for a long time my figures have wanted to be made of meat. It was the beginning of the 70's.

But for some time now their characters were no longer flat. They had begun to gain corporeality, volume, and at the same time they had been confirming their belonging to a world of slow movements, of statuesque rests. “They want to be made of flesh,” he said, and at first the flesh was light, almost an aerial substance, until years later it became voluptuous like the body of that woman who flies high on a large bird.

* Taken from: Prologue of the “Tilsa” catalogue.

Lima Art Museum, 2000.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 91, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2014 Asociación Peruano Japonesa