Haru Hashimoto was born on July 10, 1903, in Japan, Aichi-ken, Nakashima-gun, Heiwa-mura, to Manjiro and Masa Kataoka. She was the second of six children.

She came to San Francisco via Hawaii by ship on January 10, 1923, as a young 19-year-old bride of Koroku Hashimoto (born Meiji-33, June 22), whose marriage on December 9, 1922 was arranged in the traditional omiai by a baishakunin (go-between, also called nakodo). Koroku had returned to Japan when rumors of the 1924 Exclusion Act curtailing “picture brides” circulated in the community.

Haru was anxious to leave home after her mother passed away when Haru was 18, followed by her father’s remarriage by the time she was 19. “I wanted to go far away,” recalled Haru. Her father told her, “if you want to go, you should.” Her stepmother didn’t want her to go, but Haru was already determined to leave at the time of her mother’s death.

Haru and Koroku were among six Japanese in first class during the 17-day journey across the Pacific Ocean. The sea was rough to Hawaii, with everyone suffering seasickness. They spent one night in San Francisco and boarded a train for Los Angeles the next day. Haru went shopping for western clothes as she only had kimono with her.

Koroku had been in Los Angeles with his uncle, Ryusaburo, who opened Mikawaya, a mochigashi-ya, or Japanese confectionery, in Little Tokyo. They stayed with Ryusaburo and his wife in a duplex on Central Avenue until Ryusaburo left the business in 1926 to Koroku and Haru and returned to Japan.

The first shop was located at 365 East 1st Street, near Central Avenue from 1923 to 1926. At the time, there were five working in the shop—an anko (sweet bean) maker, Ryusaburo and his wife, and Haru and Koroku. “Now we have seventy people.” Haru smiled.

When Nishi Hongwanji was built at that location, they relocated to 119 North San Pedro for five years, from 1926 to 1931, and then to 244 East First Street until the evacuation.

Haru recalled her homesickness when she first arrived in Little Tokyo, compounded by her loneliness because she was unused to being among a lot of people. “I liked to read. I didn’t have friends yet, but we had two dogs. And I did the housework,” said Haru. “When it was one to one, I was O.K., but when there were three or four people, I would retreat.”

She returned home to Japan in her fifth year and stayed about a month. She cut her visit short because of a growth of some kind in her head. She’s not sure if it was a tumor, but prolonged severe headaches over three years, it resulted in the loss of hearing in her left ear.

They left their shop in someone’s care and returned to Japan in 1938, and in 1939, their first child, Sachiko, was born. They thought of living in Japan and raising their child there. A telegram arrived that said, “Things are quiet,” but six months later talk of war started, and they decided they had better return to America. They returned on March 1, 1941.

After December 7, 1941, evacuation of Japanese Americans began in February 1942. The Hashimotos were the last to leave Little Tokyo. On May 27, 1942, they left Union Station for Poston, Arizona. Their second child, Frances, was born in Poston in 1943.

At the end of the war, they left on August 18, 1945 and returned to Little Tokyo. While in camp, they had paid $100 to Zenshuji to reserve an apartment in a two-story building occupied by about a dozen families. They reopened their business on December 23, 1945, next door to where they were before the war, at 244 South San Pedro Street. They were able to reopen so quickly because the production area in the shop was the same as the place before. While they were in Poston, their space was occupied by an African American-owned restaurant. He left after the Hashimotos returned, as did all the other Black-owned businesses.

It was tough to run a business after the war. All transactions had to be in cash, deliveries weren’t made, and foodstuffs were rationed, such as sugar and flour. Customers bought whatever they could. “It wasn’t like now, where customers can choose from a variety of manju,” said Haru. “One cost 5 cents, six for 25 cents.” Because mochigome, sweet rice, was rationed, they had to limit the quantity per customer. Customers stood in line out the door.

In 1948, they purchased a four-unit apartment in East Los Angeles under Frances’ name since Koroku and Haru weren’t citizens. They eventually became naturalized citizens.

On February 12, 1958 Koroku suffered a heart attack at the age of 57 and passed away. Frances was 14 and Sachiko, 19. Haru and Sachiko ran the business for about 20 years until Frances later joined the daily running of the business. Haru had help from friends like Gongoro Nakamura, who helped with legal matters, and Frances, Sachiko, and two nephews who lived with them helped in the shop. Frances was in her fourth year of teaching elementary school when she quit to devote full-time to the shop because Haru suffered whiplash in an automobile accident. Sachiko, by that time, was married with four children.

When Little Tokyo came under redevelopment and the future of some businesses on East 1st Street became unpredictable, Frances realized Mikawaya needed to think of another location for production. She said, “I thought that if we didn’t get a facility, we would die.” Although there was some criticism, Frances went ahead and built a 10,000 square foot building on 4th Street, one block east of Alameda. As it turned out, it was a wise move. It was later expanded to include one building between and another one behind.

Mikawaya’s future and fortune saw a turning point with the invention of “mochi ice cream.” In 1984, Frances’ husband, Joel Friedman, decided to “get out of L.A.” because of the anticipated crowds during the 1984 Summer Olympics. He visited Japan and went around trying different foods. At one point, he had something that resembled mochi and experienced a “wow” revelation. “Wow! What if we put ice cream in mochi,” he thought.

When he returned home, they started experimenting with different processes. The trick was “how to put ice cream into hot mochi.” In April 1994, they test-marketed the product in Hawaii. “Everybody in Hawaii knows what mochi is,” Frances explained the rationale. They started at one restaurant, selling it in a 12-pack container. Later, it became a retail pack. The mochi ice cream did really well.

They began with six flavors: strawberry, mango, vanilla, green tea, coffee, and ogura (red bean). Chocolate was added later. Mochi ice cream is sold all over the United States—in Asian markets and specialty stores, such as Trader Joe’s and Costco. Internationally, it’s sold in Saipan, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

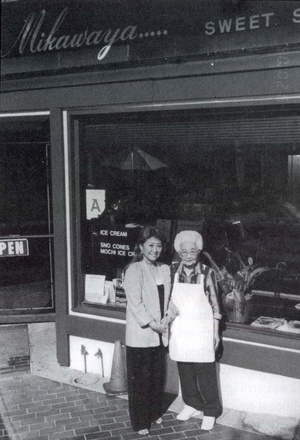

Mikawaya today has four branches in Los Angeles County: Little Tokyo Square, Japanese Village Plaza, Gardena, and Torrance. They have one branch in Honolulu at Shirokiya.

As Haru reflected on her 100 years of living, she said, “The happiest time in my life is now—I have children, grandchildren. It would be even happier if my husband were here. I feel nothing but gratitude for my life here.” Frances interjected, “Above all, it has been the store. Her first baby was the store. My father wanted to travel and he went alone. She said they could travel when they turned 60, but he passed away before that. She loves the store, and she really loves to be with people. Ever since I can remember, she’s loved to give away things. She really, really likes to be here—that’s her ‘tanoshimi’—to mingle with people.”

Haru is content regarding Mikawaya’s future—“I’ve left it in Frances’ hands.” Her goal is to live until 104. The family has held memorial services every year for Koroku, and Haru’s desire is to see the fiftieth year. “Dooshitemo”—whatever it takes—“I can’t die till then.”—Haru smiled and laughed.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices Little Tokyo: Changing Times, Changing Faces, in January 2004. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2004 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California