Over the past decade or so, Latin America's high economic growth rates have been the focus of attention, and many Japanese workers living in Japan have returned home in anticipation of this situation. However, the economic downturn has worsened over the past two years, and the situation in Brazil, a major country, is particularly not looking good. However, many South American countries export and import goods, services, and energy to Brazil (Brazil, which has a large land area, produces electricity and natural gas, but purchases electricity from Paraguay and gas from Bolivia), and the impact of Brazil's recession, which accounts for more than half of the region's gross domestic product, is extremely large. In addition, the fraud scandal at the state oil company Petrobras has shaken the political world, and President Dilma's administration is beginning to show signs of decline. Emerging countries that rely on the export of primary products, which are easily affected by international prices, will quickly lose their growth model when the prices of crude oil, grains, mineral resources, etc. fall. This is also a major cause of the slowdown in the Chinese economy, which imports a large amount of all kinds of raw materials from the world, but emerging countries that have similarly relied on primary products are also suffering a major blow.

The biggest problem is that, despite warnings about this for a long time, no Latin American country has implemented fiscal management (increasing foreign exchange reserves and reducing deficits) that can deal with this situation. The economies of Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela are the most sluggish, while the other countries are relatively healthy (even though their growth rates have slowed, their inflation and unemployment rates are kept low, and their central banks have a considerable amount of foreign exchange reserves, so they can deal with exchange rate fluctuations). In addition, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Paraguay, Bolivia, and other countries are attracting attention as destinations for foreign investment, and despite the unclear political factors and corruption scandals, each country is considered to be relatively promising in its own way. In all markets, the middle class, which has expanded over the past decade, has not completely disappeared.

On the other hand, even in countries that have implemented socialist policies (prioritizing poverty reduction and social work with revenues from export taxes on oil and grain), disparities have widened despite improvements in poverty rates, and discontent among the poor and middle class has exploded. Countries that have implemented handout policies may see their finances worsen further. As purchasing power cannot be maintained, pressure to raise wages, improve social security, education and infrastructure will increase. Furthermore, strikes may increase due to the deterioration of labor-management relations, and more countries may find it politically difficult to run their governments (even Argentina and Chile, the top student in South America, are facing such concerns). In Brazil, the large-scale protest demonstrations that occurred before last year's FIFA World Cup are still fresh in our memory, but rallies and road blockades have occurred again in various places recently.

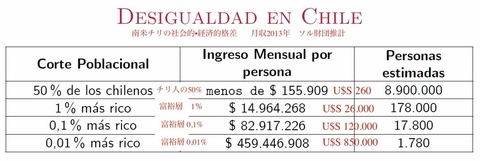

Half of the Chilean population (8.9 million people) has an average monthly income of $260, and the wealthiest 1% (178,000 people) earn $26,000 (equivalent to about 3 million yen), 100 times the income of ordinary people, but 10% of them (17,800 people) earn $120,000 (equivalent to 15 million yen) a month. Other countries where wealth is concentrated in the top 10% are said to be Brazil and Mexico.

According to a Japanese person who returned home, in many countries, apart from some food and transportation prices, everything is more expensive than in Japan, and incomes are not keeping up with rising prices, resulting in an ever-widening economic gap. On the other hand, Japan has a stable economy, so people can manage their finances and there is also room to choose in terms of price and quality when purchasing goods and services. Therefore, if you save money, you can ensure a certain standard of living, he points out. In South America, he says, this is becoming very difficult.

Why does it seem so vibrant? It is because of the existence of the black economy, which accounts for 25% to 60% of Latin American countries, with an average of 40%. You can sense its movements in the market, but there are no records of commercial transactions or salary payments, and the movement of money generated there is not reflected in the country's gross domestic product statistics.

All countries are trying to improve this shadow economy by reforming their tax systems and strengthening measures against tax evasion, but in South America, where inequality is more serious than in Africa, there is a weak sense of norms and low compliance with tax obligations.

In recent years, the number of small family-run shops selling ramen, gyoza, original Japanese cuisine, etc., which were started with funds saved in Japan, has been increasing in Lima, Peru. On the other hand, the advancement of Japanese companies into the retail industry has also been a hot topic, and last month, the first store of "KOMONOYA" (600 soles per item), a brand of Osaka-based Watts Co., Ltd., opened in a shopping mall in Lima, attracting wide coverage from local media1 .

In addition, major automobile manufacturers are expanding their investments in Mexico and mineral resource development projects in various parts of South America are showing strong growth. In any case, it is likely that Japanese retailers will become more proactive in targeting overseas markets in the future, and will increasingly pay more attention to the Latin American market.

One role that has been attracting attention in this movement is that of Japanese descendants as facilitators. With their understanding of the structure and hidden rules of local society and their connections in various industries, they can help Japanese companies expand into South America by sorting through vast amounts of information and introducing them to reliable experts. Naturally, they are global human resources that can help avoid risks and save money.

However, not all Japanese descendants meet these conditions, so utilizing Japanese descendants does not necessarily mean business success. Starting a business for the first time in an unfamiliar place requires understanding very detailed information such as laws, accounting, taxes, and industry regulations. Sometimes creating powers of attorney and contracts to access them can be a major obstacle. In Japan, a simple power of attorney can do a lot of work, but in South America, the formal requirements are complex, and when exercising the power of attorney, the wording and the provisions on which it is based differ depending on the institution. In addition, exercising such a power of attorney requires certification procedures on both the Japanese side and the other country, and sometimes lawyers from both countries must make very detailed adjustments. Even getting the Japanese side to understand this can take a lot of effort and time.

The potential of Latin America has always been recognized, but as a business destination, there are still many difficult aspects, except in areas where major companies and multinational corporations have expanded, such as high levels of corruption, low compliance with laws, underdeveloped infrastructure, and unclear related procedures and application of laws, which pose great risks to ordinary Japanese managers. Japanese migrant workers who have returned from Japan have been aware of this and have developed various businesses, but there have not been many successful cases.

However, even though the growth rate is slowing, the middle class's growing willingness to spend in recent years is still attractive to retailers. Even though it is Latin America, each country has completely different characteristics, so detailed information must be analyzed for each region and industry. Statistics from public institutions are not necessarily reliable. President Moreno of the Inter-American Development Bank believes that instability in the region will continue until around 2020, and warns that even countries with high growth rates may suddenly experience a slowdown due to domestic and international changes. In this situation, it is still necessary to see for yourself, walk around, and meet with industry insiders and experts in person to exchange opinions. It is too reckless to take the first step based only on advertising images and government information on investment attraction.

Notes:

1. Watts Co., Ltd.

- Japanese 'Komonoya' seller sells its products in only 6 pieces

- Japanese Konomoya first operations in Latin America with first contact in Peru

reference:

Related Discover Nikkei articles

-Recent economic growth in South America and Japanese descendants

-Inequality, Security, and Japanese People in South America (2 parts)

-Economic growth in Latin America and Japanese communities

Latin America related articles in Spanish

- The recovery, the big one, perpetuated by Latin America

- EY CEO for America: “It’s convenient to stay in Latin America”

- ¿ Is this American Latin American preparing for a fight?

- China is convening a banquet for Latin Americans

- Latin American English tributes and cries of the decades

- FMI: Peruvian economy stewardship in Latin America and 2015

- Luis Alberto Moreno: The American Latin American economy will change in 2020

© 2015 Alberto J. Matsumoto