While perusing this beautiful and bountiful 470-page tome affording its lucky readers a temporal, spatial, and sociocultural journey relative to San Jose’s Japantown, I reflected upon my personal journey regarding this historic place. It was secured by my reading of Stephen Misawa, ed., Beginnings: Japanese Americans in San Jose (1981) and Timothy J. Lukes and Gary Y. Okihiro, Japanese Legacy: Farming and Community Life in California’s Santa Clara Valley (1985). It was humanized by my oral history fieldwork with Kibei Harry Ueno, major dissenter in the Manzanar Revolt of December 5-6, 1942; Kibei Yuriko Amemiya Kikuchi, celebrated dancer and choreographer with the Martha Graham Dance Company; Nisei Eiichi Sakauye, visionary community leader and founding member of the American Loyalty League of San Jose, which was formed prior to the Japanese American Citizens League; the 11 mostly Nisei interviewees and eight primarily Sansei interviewers for the San Jose study site in the Regenerations Oral History Project: Rebuilding Japanese American Families, Communities, and Civil Rights in the Resettlement Era (1997-2000); and two featured narrators for the Big Drum: Taiko in the United States project (2005-2006), Roy and PJ Hirabayashi, the Sansei moving spirits of San Jose Taiko. Finally, my journey was made palpable by my periodic visits to San Jose Japantown and participant-observation in its vibrant civic, commercial, cultural, and religious life.

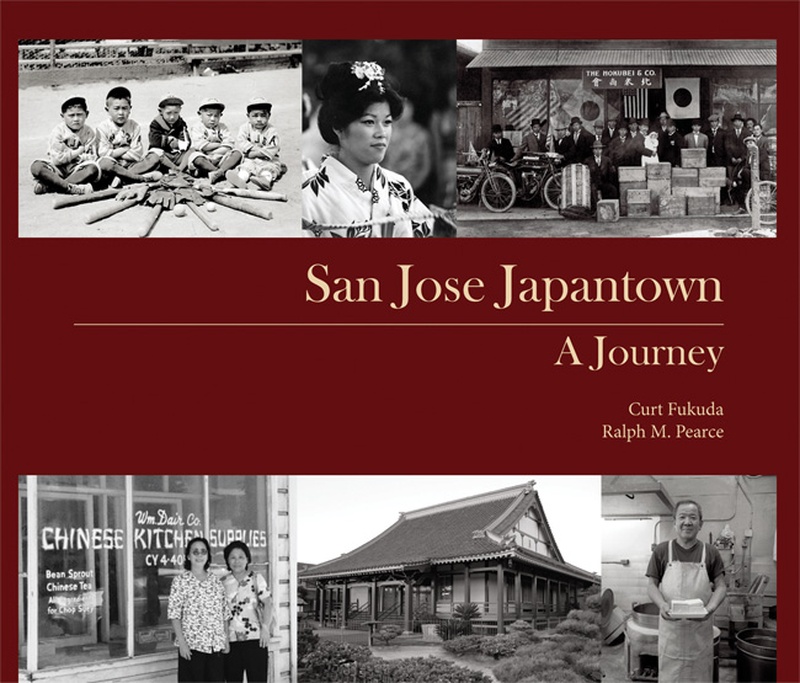

An altogether striking achievement of community collaboration, the book under review is co-authored by Curt Fukuda and Ralph M. Pearce, with a huge helping hand from the other three members of its cohesive production team (Jim Nagareda, project lead; Janice Oda, designer; and June Hayashi, editor). How this stalwart team congealed and the book assumed its ultimate form represent extraordinary journeys of their own sort, and both of these are admirably detailed in San Jose Japantown. Further information on these journeys is available via the excellent YouTube video “Meet the Authors: San Jose Japantown: A Journey.”

As for the overarching journey of San Jose’s Japantown, it is organized into fourteen chapters, eight of which are appropriately themed and chronologically sliced to encompass the full sweep of the district’s growth and development from 1890 to 2010, with the remaining six given over to depicting Japantown’s pre-history, its pre-World War II pioneers, its post-war movers and shakers, its sports scene, its religious institutions and its foodways. All of these elegantly composed and precisely edited chapters are infused with well-chosen stories that are both meaningful and memorable, and these tales are resourcefully fitted into a resplendent design that adroitly accommodates text with a plenitude of captioned photographs, other illustrative items, and sporadic informational sidebars.

Two aspects of this exemplary book that I found both illuminating and moving were the authors’ cosmopolitanism and their consciousness of standing on the shoulders of giants.

One manifestation of the first quality is the democratic and just attention accorded those living and working within the Japantown community of non-Japanese ancestry (people of Chinese, Filipino, and African descent). A case in point of the second quality is the dignified homage paid to the late Helen Mineta, whose unfinished history book written for the 1990 Japantown centennial is not merely repeatedly noted by Fukuda and Pearce, but also judiciously drawn upon by them for excerpts to supplement and enhance their narrative.

In reading San Jose Japantown, my own personal journey of this site was expanded and embellished. I found out, for example, that Yuriko Amemiya Kikuchi’s mother, Chiyo Amemiya, was a midwife, that Yuriko taught dance (buyo) to the Japantown Nisei girls, and that the Amemiya home (and midwifery) on North Sixth Street is still standing today.

I also discovered that Gary Okihiro, after the publication of his co-authored Japanese Legacy, organized a meeting of local institutional representatives and informed them of a need for an organization to preserve San Jose Nikkei history, an action leading to the founding of the Japanese American Resource Center by Eiichi Sakauye and others, which in turn morphed into the Japanese American Museum of San Jose, the present book’s publisher. I furthermore became aware that the postwar resettlement years were the “peak years of Japantown,” and that notwithstanding the migration of the Nikkei population to the suburbs, “Japantown was still the center for the Japanese American community.”

Additionally, I was alerted to the vital role played by the Sansei in the 1970s to 1980s reawakening of and rejuvenation of Japantown and Japanese culture. In this connection, I was informed that Roy Hirabayashi, who as a San Jose State University student was aligned with Asians for Community Action and was involved with Asian American studies, would afterward with his wife PJ Hirabayashi (whose 1977 urban studies master’s thesis at San Jose State was “the first serious study of San Jose Japantown”) fashion San Jose Taiko into a dynamic protean marker of identity for democracy, social justice, civil and human rights, Japanese/Japanese American/Asian American culture, and San Jose Japantown.

I am certain that many other readers will find within the pages of San Jose Japantown: A Journey their own reasons for celebration.

SAN JOSE JAPANTOWN: A JOURNEY

By Curt Fukuda and Ralph M. Pearce

(San Jose: Japanese American Museum of San Jose, 2014, 470 pp., $65.25, hardcover)

*This article was originally published by the Nichi Bei Weekly, on July 23, 2015.

© 2015 Arthur A. Hansen / Nichi Bei Weekly