It all began while doing research for a film on Stanley Hayami, the bright and promising young man killed in the final days of the war while serving in Italy as a member of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team. He was just 19, and his short, tumultuous life epitomized the tragedy of incarceration. His diary, letters, and drawings describing his boyhood at Heart Mountain and as an infantryman with the 442nd RCT comprise a prized collection at the Japanese American National Museum.

Although the film, A Flicker in Eternity, focused on Stanley and his immediate family, including his sister Grace (Sach) and brothers Frank and Walt, he also had a cousin, Paul Nakadate, a well-known figure in Japanese American history for his role as vice president of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee (FPC). The FPC advocated for clarification of the governmental order that required all young men of draft age to register to serve in the military while they and their families were held in camps.

Despite the fact that Stanley and his brother Frank (as well as several cousins) were among those who valiantly served in the 442nd, there were clearly family differences concerning the draft. Paul’s passionate stance on its illegality undoubtedly affected the Nakadate and Hayami families. Though there was no mention of Paul in Stanley’s diary, the cousins had spoken about the importance of Constitutional rights in respect to the draft, according to Stanley’s brother Walt. Although Stanley told Walt that he “kind of agreed” with Paul, when ordered to serve Stanley went.

I could find little written about Paul Nakadate so turned to Frank Abe, director of Conscience and the Constitution, the landmark film on the subject of the Heart Mountain resisters. I recall him saying something about Paul’s story being “very sad” because he was “disowned” by his family. I asked if there were any Nakadate family members around, and he referred me to Paul’s grandson, Jeff.

The name Nakadate was very familiar to me. “I wonder if he’s any relation to my auntie,” I thought fleetingly. My aunt, born Taneko Yamato, was my father’s sister married to Mickey (Michiyo) Nakadate, but I figured Nakadate was a fairly common Japanese surname. Uncle Mickey, my aunt’s husband, died before my family moved back to California from Denver after the war. I was only 3 years old when his body was found at a local swimming pool the morning after he suffered a fatal heart attack at age 42. I realized that I knew nothing about Uncle Mickey except he was a dentist and had served in the military. I’d never heard anyone in our family mention Paul. Surely a man of his stature would have been talked about.

Last month, I happened to invite my cousin Glenn (Uncle Mickey’s son) to a screening of A Flicker in Eternity for the Friends and Family of Nisei Veterans (FFNV) near Glenn’s home in Las Vegas. In the film Paul’s photo appeared on the screen. That’s when Glenn turned to me and whispered, “That’s Paul, my father’s brother.”

After recovering from the shock that a WWII dissident/hero was related, I suddenly recalled Frank Abe’s comment that Paul’s family had “disowned” him. What family was he talking about? I immediately asked Glenn if he knew how his father felt about Paul’s involvement in the FPC. He told me that since Paul’s three brothers, including his father, served in the military, there was obviously some turmoil in the family. He explained that Uncle Mickey, who served in the Navy Reserves before Pearl Harbor but forced to resign in 1941, was the eldest son and perhaps the angriest. He also said according to family legend, Paul’s other two brothers, Shoji and Kakuya, were drafted. Shoji ended up being shot in the leg while landing in Italy on an amphibious boat, and Kakuya served in the Signal Corps in the Philippines.

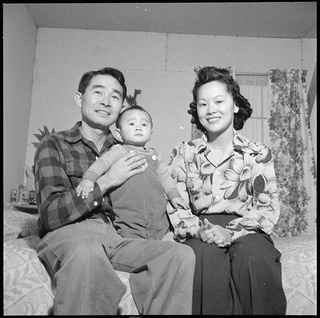

Paul was then a 29-year-old father of an infant son (Tomio) and thus not required to register for the draft. Fellow FPC member Isamu (Sam) Hoshino called Paul “scholarly” and given the job of presiding at FPC meetings. Paul articulated his position on the draft in a letter to the editor of the Heart Mountain Sentinel: “If we as citizens accept orders as a matter of course or well knowing the invalidity of the law, we are not good citizens.”

In cursory research, I had trouble finding even the most basic information about the man who seemed to represent the FPC in his writings. From the Conscience and the Constitution website, I read that Paul Nakadate was born on August 18, 1914, in Montebello but grew up in San Diego. After graduating from San Diego State, he was an insurance salesman in Los Angeles before being sent with his family to Heart Mountain.

Looking for more information, with Glenn’s help I finally located Jeff Nakadate, Paul’s grandson, who unfortunately had little to relate about his grandfather. He responded in an email that his father was not very close to his grandfather, adding that his grandmother, who died in 1999, also shared little about her husband. When I tried to reach Jeff’s father Tomio, I got a disconnected number.

Through further reading, I found that as a result of Paul’s activities as an FPC leader, he was arrested and sent to Tule Lake. Tried separately from the 63 men who refused to register for the draft, he and six other FPC officers were found guilty of conspiring to counsel, aid, and abet violation of the Selective Service Act. Considered among the most culpable, he was sentenced in 1944 to four years at the maximum-security federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. In 1945, the federal Court of Appeals in Denver overturned their convictions because of an error in the phrasing of the legal instructions submitted to the jury. Ultimately, they were fully pardoned by President Harry Truman in 1947.

Throughout the years, FPC leaders were strongly criticized for their position on the Constitutionality of the draft. They were even labeled “Fascists” by war hero Ben Kuroki, who said in an interview that they were “no good to any country.” Among others who denounced them were the JACL, the Sentinel, and even a group of Buddhist and Christian church leaders who urged them to recant their actions.

More recently, members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee have finally received praise for their unpopular stand. Even the JACL issued an apology and publically honored them in 2002. Once considered traitors, at long last they are being recognized as community heroes.

As for the Nakadate family, I learned from Glenn that most of them, including Paul, lived in and around the Boyle Heights area after the war. Sensing no family disharmony, Glenn even remembered helping out at his uncle Paul’s produce stand when he was a young boy. Apparently, Paul was the only Nakadate brother who had difficulty finding work commensurate with his education and intellect. In spite of the official pardon, his prison term undoubtedly left an irreversible stain on his record. One thing was clear: no one, particularly Paul’s mother and father, ever spoke about the war.

Sadly, Paul Nakadate, who died at age 49 of a heart attack, never lived to hear the accolades he so justly deserved. It seems that his immediate family members, many who are now gone, either knew little or chose not to talk about this man who played such a powerful role in our collective history.

I thought about John Okada’s novel, No No Boy, the acclaimed story of the internal turmoil of a man caught in the middle of strained relationships after the war. Because family members chose not to talk about Paul, he died without many of us really understanding who he was and what he stood for. I also came once again to the conclusion that family secrets are difficult to unravel unless someone close to the facts is willing to disclose them. Sharing our histories—especially the difficult parts—may be the only way future generations can learn what happened during this not-to-be-forgotten time in our history.

© 2014 Sharon Yamato