3. Breaking the Silence : The Reparations Movement from the 1970s to the 1980s

Young second and third generation Japanese Americans, inspired by the African-American civil rights movement and minority movements of the 1960s, also began to voice their support for the creation of Asian studies departments at universities and for the increase in Asian and female faculty. Kashima, who was just a baby at Topaz internment camp, says that by this time he was at the forefront of demonstrations with Gordon Hirabayashi's younger brother, Jim. Here are the words of a third generation Japanese American:

Without the black movement, we wouldn't exist. It was certainly from that point on that we started to understand who we were and we started to feel proud of who we were. We also started to become very aggressive, almost politically militant, and to say what we were, that we were now standing up and we were not going to take it anymore .

This awakening motivated the second and third generation Japanese to believe that they could no longer tolerate what had happened to Japanese society, and that a reparations movement was necessary to remove the guilt and shame suffered by those who had been incarcerated. "The reparations movement is a rejection of the stereotype of a docile [Japanese American], and symbolizes the birth of a new [Japanese American], one that recognizes and corrects injustice when it occurs." 2

In 1970, the JACL National Convention resolved to demand an apology and compensation from the government for "the internment, detention, and denial of civil and constitutional rights to Japanese Americans during the war." In response, the Seattle JACL recruited volunteers to investigate the matter, and among the volunteers was Henry Miyatake (Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4 of this series). Henry had been researching numerous legal precedents at the University of Washington Law School library in preparation for compensation. Henry and his team established the "Seattle Eviction Compensation Committee." Discussions continued to reach an agreement between Edison Uno's proposal to receive compensation as a trust fund for the Japanese American community and use it to establish a community center and museum, and Henry's Seattle proposal, which said, "That would provide no benefit to the Issei living in the countryside. Compensation should be individualized." The Japanese American community said, "There's no need to stir things up now," and JACL executives said, "Monetary compensation would cheapen the sacrifices of Japanese American soldiers and could reignite anti-Japanese sentiment."

It was also necessary to inform the general public about what happened to the Japanese community during the war. Many American citizens who learned about America's dark past through the media became angry, and around this time some survivors began to give interviews and write autobiographies.

In July 1980, the Congress-appointed Committee on Wartime Relocation and Internment was launched to finally begin the compensation movement in earnest. The committee spent a year and a half reviewing all documents related to the forced evictions and internment, and reexamining the government and U.S. Army commands. It also held public hearings in various parts of the U.S., including Alaska, to hear from first-hand survivors. At the hearings, more than 500 survivors spoke for the first time about things they had kept secret from their families. The heavy testimonies of survivors, heard directly from the committee members, were delivered to ordinary households through newspapers and television, and touched the hearts of many. In 1983, the committee compiled its findings in a report, Personal Justice Denied , which stated that the internment was not due to military necessity, but was due to racial prejudice, wartime hysteria3 and a lack of political leadership. Four months later, it recommended a remedy plan to the government, including an official apology, individual compensation, and support for educational activities.

We were relieved, but we couldn't rest. Again with the help of Congressmen Norman Mineta and Robert Matsui, and Senators Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga, many compensation activists made frequent trips to Washington DC to persuade each and every member of Congress. It was truly a grassroots movement. On September 17, 1987, the 200th anniversary of the promulgation of the US Constitution, the compensation bill was passed by the House of Representatives. On April 20, 1988, it was passed by the Senate. On August 10, 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. It was two years later, in October 1990, that the oldest surviving internment camp survivors were given an official apology and $20,000 compensation each. Unfortunately, it didn't arrive in time for Esther.

Official apologies and compensation helped heal the wounds suffered by the Issei and Nisei and helped them regain their lost confidence, but before that could happen, it was necessary for Japanese Americans to speak in their own words about their experiences, which they had kept silent about. This article will tell you about the first Remembrance Day, which finally gave them the opportunity to speak out, the public hearings, and the retrial of Gordon Hirabayashi, which gave momentum to the compensation movement.

First Remembrance Day - 1978

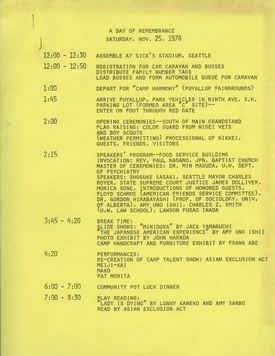

When the reparations movement was struggling, two young people came to the Seattle Eviction Reparations Committee. They were Chinese playwright Frank Chin and a young third-generation American, Frank Abe4 . It was Frank Chin's idea to plan a "Day of Remembrance" in 1978, an attempt to relive the forced eviction that had occurred 36 years earlier. Notices to the Japanese community were posted on telephone poles, just like the forced eviction notices, and a convoy of buses and cars was to travel from Seattle to Puyallup, just like they had done 36 years ago. One of the committee members had this to say:

When we planned it, we were actually talking about how many people would come. We thought if we got 100 people, we'd be lucky. When I got to the stadium and saw the line of cars, I thought, "Wow -- how amazing!" "They finally got it!" I couldn't believe the crowd in front of me. It was a real eye-opener.

When we arrived in Puyallup, each person was given a family number tag and placed inside a barbed wire enclosure. In the barracks rooms that had been specially prepared for the day, there were displays of items that had actually been used in daily life, a share house with politicians and survivors, a potluck lunch, and even a talent show. In response to questions from third and fourth generation survivors who had never been incarcerated, some survivors were seen slowly speaking.

I think a lot of people were crying and very emotional. But my experience was probably quite different from other people's. I felt very powerful and very happy that we were all there.... It definitely motivated me to work with people to make it more public, to get people talking about their experiences, to find out more. It was kind of cathartic. The day of remembrance allowed people to talk.... So for us as a community - it was very therapeutic. 6

Notes:

1. Yasuko Takezawa, "Japanese American Ethnicity: Changes through Internment and the Reparations Movement," University of Tokyo Press, 1994

2. Sandler, W. Martin. Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans During World War II. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Inc., 2013.

3. Kashima takes the position that it is difficult to imagine that "wartime hysteria" is directly linked to the forced evictions and internment. The reason is that the hysteria occurred after the attack on Pearl Harbor and was mainly limited to the West Coast, but the decision to force evictions and internment was made in Washington DC, and plans for the internment of Japanese Americans had been drawn up in Washington DC even before the war began. He says that there is a possibility that new evidence will come to light on this matter in the future.

4. Abe, Frank. (Director/Producer) (2011). Conscience and the Constitution: They fought on their own battlefield [Documentary Film]. Resisters.com Production.

5. See above, "Japanese American Ethnicity: Changes through Internment and the Reparations Movement"

In fact, the attendance reached 2,000 people.

6. See above, "Japanese American Ethnicity: Changes through Internment and the Reparations Movement"

*Reprinted from the 137th issue (April 2014) of “Children and Books,” a quarterly magazine published by the Children’s Library Association.

© 2014 Yuri Brockett