More than a job for the extras

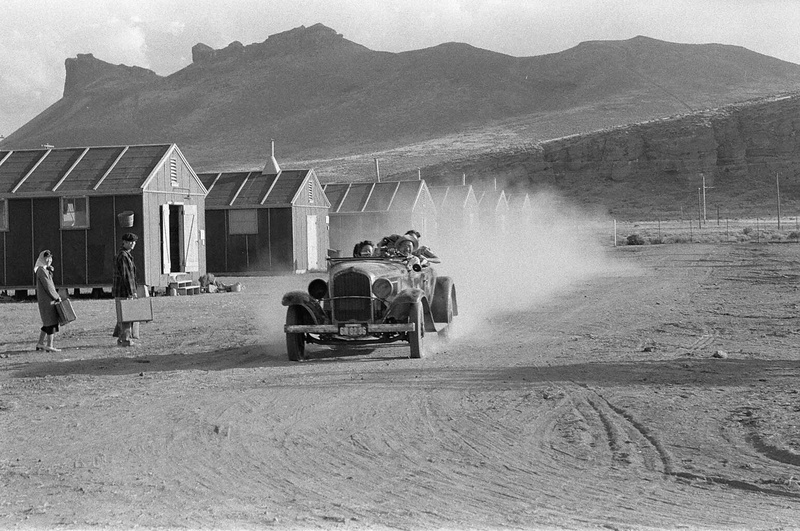

The 1975 production used crowds of Japanese American extras, many of whom had themselves been imprisoned in Manzanar, Tule Lake, or other camps.

Korty said, “In most movie situations, the extras are there for only one reason, and that’s money… This was a totally different situation because all these extras were emotionally involved in the project. And they wanted to help and they wanted to do these things. It made all the difference in the world.”

“I have to tell you, this was a loyal group of people,” Yap said of the extras who came to Tule Lake to be part of Farewell to Manzanar. The motel rooms where they stayed were bare-bones when available at all. He said “I think actually some people camped” in things like motor homes. Some had traveled long distances to take part. The Houstons wrote in their memoir, “one man planned his summer vacation so that he could drive out from New York City with his family.”

Yap said “We’ve always had a picnic or something” to thank extras, but this was different. Families would stay on the set after their parts in the filming were done. They would help with the equipment or bring beer—he remembered worrying about the beer on the set with the crew still working—but all went well.

He said, “If they didn’t know before, they knew after, that this was historical, what they were doing. The story that we were telling, but also the story that you’d be living for 3 to 5 days or in my case, 12 weeks.”

Parker said the extras would offer suggestions about wardrobe and other details, and some of them made props for the film by the same methods they had used during the war: flowers made from tissue paper, geta clogs made from scrap wood with braided rags for the toe thongs. She remembered how some of the elders among the extras created a distinct social center around a picnic table in one of the bungalows, where they would sit with a jug of water or coffee available, playing cards or working on props.

Korty recalled that Kinoshita, the set designer, distributed getas to all the members of the cast and crew, in their correct shoe sizes, to serve as mementos at the end of the production. He also remembers Kinoshita making mochi with a mallet in traditional style.

Breaking local ice

It’s difficult to know what attitudes may have been changed in the Tule Lake Basin by the film production. But the arrival of free-spending, charm-dispensing Hollywood producers making a film about the incarceration experience may well have helped future Tule Lake Pilgrimages.

The Tule Lake Basin has a history of political conservatism that follows partly from the circumstances of its settlement. Much of the Basin was opened to agriculture when the Bureau of Reclamation drained and irrigated lands that had formerly been part of broad, shallow Tule Lake. It distributed much of the new farmland in the form of homestead grants to white veterans of World Wars I and II. Because of the Tule Lake Basin’s remote location, the Tulelake post of the American Legion veterans’ group took on some functions of local government through the middle of the 20th century. The area’s leading citizens as of the 1970s were especially likely to be military veterans, some of whom had been in combat overseas.

The year of the film production, 1975, was also the year of an early Tule Lake Pilgrimage (either second or third depending how prior events are counted). One participant has said that during the April 1975 Pilgrimage—which would have been just months before the film was made—some local people in a pickup truck with a shotgun circled menacingly late at night outside the high school gym where pilgrimage members were sleeping; the sheriff arrived and calmed a situation that could have turned worse. (Since then, occasional threats have surfaced around Pilgrimages. There was a veiled threat to an organizer in the 1990s; windows of an empty Pilgrimage tour bus were shot out in Klamath Falls during the 2006 Pilgrimage’s cultural program.)

In summer 1975, Lope Yap, Jr. walked into the bar of the Sportsman Lodge in Tulelake and rented a room for seven dollars a night. He downplays the quiet courage that took. The Sportsman of the 1970s is remembered unfondly in some local quarters as a bastion of Tulelake’s conservative and frequently racist old guard.

Yap did say that at the Sportsman, “you could never let down your hair down and relax about racial issues. You had to just be, kind of, aware. Particularly when you’re talking about people who were kind of raised in a very bigoted environment. And then the whole World War II thing is—is a big deal.” Regarding the incarceration: “There are still people there who probably still feel like, ‘what was wrong with that, they were trying to kill us.’” He said the Sportsman was the scene of a few incidents during the first week of filming between extras and locals: it “got kind of touchy once in a while but never got to blows.” Tensions eased after a while but “The first night I got there was kind of weird.”

(This was a time and place where the incarceration of Japanese Americans was not necessarily remembered as a wrong. Yap’s own father, who spent World War II as a fugitive from Japanese occupying forces in the Philippines, disapproved of his son’s part in the production. Yap said he told his father, “Society’s got to grow,” and went to work.)

By Yap’s account he soon was getting help in his hunts for supplies, catering, props, and locations from important local figures: owners and staff of the Sportsman, and Bill McBride, butcher at the nearby small supermarket, and the area’s only Highway Patrol officer (“he was his own sergeant”).

As Yap and Korty recount it, nothing at Tule Lake rose to the level of trouble that Korty had faced the previous year in filming The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman in the deep South. There, Korty said, one adjacent property owner showed his dislike for the production by revving a motorcycle during filming, and then by ostentatiously wearing a gun on his hip.

Yap describes the main production difficulties as similar to those of any filming location: disruption, dirt, telling people not to park where they normally did—the hassles when “Hollywood just came to town.” Complaints, he said, were mainly at the level of annoyance. Korty noted there were no fires or loud noises in the production. And Yap said, “We dropped a lot of money,” for example, by buying hardware for the set. And by filling every motel and trailer park in the area with cast and crew and extras.

Revisiting the film

After its first release as a TV movie, the Manzanar film had a difficult journey back to prominence.

It was first re-released to California public schools in a project begun during the politically tense last months of 2001 and partly funded by the California Civil Liberties Public Education Project. According to Korty, the major mover of that re-release was Carole Hayashino, then a professor at San Francisco State University and politically active in Marin County. Korty said Hayashino heard him complain that Universal wouldn’t spend the money to release the film and was “just sitting on it.” Hayashino took the problem to Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante, who intervened with Universal. He helped arrange a distribution of 10,000 copies of the film to California schools.

A more recent general re-release of the film was welcomed in 2011 and 2012 by interviews, events, and public conversations. Too late for some of the film participants to join in, but in time for a lot of important memories to emerge.

As of 2012, Barbara Parker was saying she hoped to turn her notes and photos from the Manzanar set into a published work. Unfortunately, she was unable to prepare them for publication before her death. By the kind permission of Mr. Narita some of her pictures are included with this article. All of the photos from the location filming are now being digitized at Densho.org with plans to make them available online towards the end of the summer.

It’s likely as the National Park Service and others begin to work more formally on curation regarding Tule Lake’s history that more stories and images from the Manzanar filming will emerge. Viewed from a greater distance in time than the 30 years between the war and the film, the Manzanar production is already recognizable as a landmark in Tule Lake’s continuing story.

* Farewell to Manzanar is available on DVD at the Japanese American National Museum Store >>

© 2015 Martha Bridegam and Laurie Shigekuni