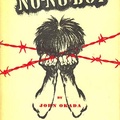

*Editor’s Note: Frank Abe shared his opinions about Ken Narasaki’s stage adaptation of No-No Boy by John Okada. Ken gave us permission to share his response to Frank’s article below.

* * * * *

I think it’s important to note that neither Frank Chin nor Frank Abe ever saw a performance or reading of the stage adaptation of No-No Boy, and since the play hasn’t been published, I don’t see how they could have read it, so one should take their criticism with that in mind: They are criticizing something they’ve only heard about second-hand.

I understand that the book holds a special place in many people’s hearts and indeed, that is what moved me to want to adapt it. But no book can be perfectly transferred from one medium to another—you cannot adapt a piece without fundamentally changing it: Books adapted to film or stage must be drastically cut to fit into two hours or less, and usually, the interior nature of novels must be lost or turned inside out because it’s usually impossible to retain the voice of the narrator. Books can take you inside somebody’s head, which is where most of No-No Boy lies; thoughts of self-hatred and self-reproach must be externalized for the stage. And sometimes, one has to change things for merely practical reasons.

In the case of my adaptation of No-No Boy, we could not stage the climactic car crash that cuts one of the characters in half, for obvious reasons, so we changed it to a knife fight. Without that literally visceral climax, Ichiro’s disappearance into an alleyway on a continued search for America simply wouldn’t play. I would argue that, for a variety reasons, that ending simply wouldn’t play onstage anyway; at least, I couldn’t find a way to make it work.

I also believed that nearly 60 years after the first publication of the book, nearly 70 years after the events of the book, we do know that most Japanese Americans, including draft resisters and No-No Boys, did find an America in which they could live, and that was what gave me the courage to write the coda that ends the play, to suggest just that.

I did not change the ending to “fxxk with No-No Boy,” I changed the ending because, in my opinion, the book’s ending simply would not work onstage, either practically or dramatically. Perhaps there was a way to do it, but I could not find it and thus had to find an entirely new solution.

I have to say that the book’s been optioned many times for film (I believe Frank Chin held those rights for some years) and no one yet has successfully produced a film version of the book. When I requested the stage rights, I discovered that no one had ever requested those rights before me. I believe that part of the reason could be the fact that it the book is devilishly difficult to adapt because it is so internal, so much of it takes place inside Ichiro’s head. I am proud of what I and my collaborators were able to create with the stage play and obviously, I stand by it.

Frank Chin was once an important artist; Frank Abe was an actor before he became a journalist and documentarian. I wish that they would remember that art is a living thing. They have a right to disagree with my version of Okada’s great story, but ultimately, I don’t think it’s possible to adapt anything without “fxxking” with it.

*Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. It is intended as a space to share different perspectives expressed within the community and to invite open dialogue.

© 2015 Ken Narasaki