If you knew my Auntie Nesan, you knew her laugh.

My cousins and I called her “Nesan” (older sister) because of family tradition; as the oldest of six siblings, all of our parents called her “Nesan,” so we did too. Her real name was Hisa. Since my name ends with “ko,” or “child” in Japanese, I asked her once if her name was actually “Hisako” when she was younger. She shook her head, emphatically. “No,” she said. “I don’t like that name. It’s not mine. Just Hisa.” She was the oldest of six siblings, the second of my grandparents’ children to survive. The oldest child, a daughter, died not long after birth, and so my grandfather named my auntie “Hisa” as a wish to grant her “long life.”

At 89 years old, my auntie did have a long life. Her passing last month has left me deeply sad and deeply grateful, in about equal parts. I can still hear her laughing now, as if she knew I was writing about her. “Oh, my goodness,” she would say. “Is that about me? Well, for heaven’s sake….” And her eyes would go wide, she’d begin to shake her head, and laugh. One of the first memories I have of my Auntie Nesan, actually, is hearing her laugh all the way across Raley’s, our hometown grocery store in Roseville, California. There was her raucous belly laugh, outrageous delight, rippling through the store. I knew she was there and that we’d find her eventually. It embodied so much of who she was: strength, resilience, vitality. In my mind her laugh was one of her greatest accomplishments because it was hers, and she owned it until the very end.

And then there are her hands. I think about all that her hands endured: all the strength that her hands evoked, all the things and feelings that she created.

She and my dad and their siblings were sharecroppers in their childhood, and they worked on farms for years before and after World War II. They worked in fruit packing sheds, one only blocks from the house where she was living when she died in Loomis, California. The family was incarcerated during the war, first at Arboga Assembly Center and then at Tule Lake, California. After the war she left home in Northern California to work as a maid in Southern California. Many Nisei women did similar work, finding whatever means they could. My Auntie Sadako remembers opening a letter from my Auntie Nesan during that time. Tears filled her eyes as she realized that her older sister had sent home her entire paycheck, keeping nothing for herself. “I’ll never forget it,” my Auntie Sadako says, to this day.

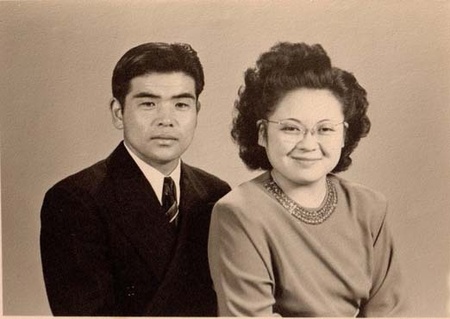

Auntie Nesan met and married my uncle Sumito Horiuchi, a Kibei who had been a member of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). They had three sons together, and they raised them in Placer County, California, close to where her parents and family had returned after the war. It must have been difficult for many reasons: Placer County was not known to be a welcoming area for Japanese Americans after the war. By the time my sister Teruko and I were born, however, Auntie Nesan and Uncle Sumito were somehow the happiest people I remember from my childhood. My dad married late, so my sister and I are the youngest cousins in our family, young enough to be their grandchildren.

So I think about her hands, a lot. These are hands that cleaned other families’ houses, after the war.

The hands that worked at cleaning at a hospital for many years—so much energy, that in her green scrubs, the hospital staff came to refer to her affectionately as “the green tornado.” The hands that created so many dishes for our family’s annual Oshogatsu gathering: the tai (sea bream), a huge oven-sized chafing dish of chow mein with special sauce waiting on the stove, king crab legs, ambrosia with canned mandarin oranges, seven-layer “finger jello,” steaming pots of oden, ceramic bowls of hijiki (seaweed) and namasu (cucumber salad). The hands that planted and harvested juicy ripe tomatoes and cucumbers in the dirt yard in front of her house. The hands that crocheted afghans, including the persimmon and chocolate-colored one I have on my couch downstairs. She gave us so much with her hands.

Auntie Nesan was physically strong, which is why it was so hard to see her so fragile at the end. Occasionally, she had begun to refer to my uncle in the present tense, although he died ten years ago. She had a hearing aid, which she didn’t like to use. There’s an uphill dirt path between Nesan’s house and my Auntie Sadako’s house in Loomis, which is well-trodden partly because of their footsteps. It was hard to see her needing to hold on to others’ hands, tightly, for support, to walk up the hill. But walk it, she did. “Getting old is for the pits,” she said several times to me, cheerfully, on my last visit to see her.

Recognizing the rapid decline of her health, my family threw her an 89th birthday party last month. My cousin Hiroshi compiled a “memory book,” and asked family members to submit personal reflections on her life. Reading them over, so many of us spoke about the same things: her laugh, her bright spirit, her food. I wrote an earlier version of this essay for her, hoping she’d be able to read it or that she could have it read to her. But when I saw her, I knew that words were not really the way my Auntie Nesan and I communicated. It was more than enough to sit next to her at the party, to hear her laugh occasionally, to watch her face as I unfolded a paper snowflake that my little girls had made for her.

As I prepare to go to California for our family Oshogatsu celebration, one that’s lasted for over sixty years, I am thinking about my Auntie Nesan. It will be our first family New Year’s without her. I am thinking about her lifetime of cleaning and cooking, mostly for others. I am thinking hard about the mostly unsung legacies of her mother, my grandmothers…really, for so many women who speak their hearts through their hands. By some measures, the lives they lead are ordinary, but what they leave us is extraordinary.

One New Year’s Day not so long ago, my Auntie Nesan was sitting at the table, and my mom came up behind my aunt and put a hand on her shoulder. Auntie Nesan didn’t say anything, but she held my mom’s hand quietly for several minutes. She did the same thing for me when I put my hand on her shoulder, later. We didn’t say anything: it was all being said.

© 2015 Tamiko Nimura