“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” (Shakespeare; Romeo and Juliet) William pretty much sums it up for me as far as names go, but it is interesting to learn about how names are determined by different times and cultures.

In Japan, middle names were not used, but in the turn-of-the-century America, Japanese pioneer immigrants, Issei, in most cases gave their Nisei children, second generation Japanese in America, Japanese middle names as well as American names. American names were given in order to ease assimilation into the American culture and Japanese names, to maintain connection to their proud heritage. This form of naming became the norm for Sansei, third generation Japanese in America: American name, Japanese middle name, and surname.

American names were usually a “flavor-of-the-day,” commonly popular names at that time. Some Japanese families who adopted the Christian faith often chose biblical names, such as Peter, Mary, Joseph, and Mark. I’ve heard that some American names were suggested by Caucasian school teachers.

Many parents put extra thought into giving their children a Japanese name. For me and my nine siblings (six sisters and three brothers), it seems to have varied. One sister, Naomi, had only the one name. Probably because it was uniquely both American and a Japanese name. One brother was given the Japanese name of Katsumi which translated into victorious. His American name was Victor. My sister Lynda Joyce Suyeko said my mother wanted Lynda, an aunt liked Joyce, so they gave her both and Suyeko was an adaption of our paternal grandfather’s Suyeichi Okamura’s name and “Sue” meant “last, the end.” LOL, five more siblings came after the “last child.”

We may not like our given name but when you become an adult, you can legally change it. For example, another brother was given the American name Clyde. None of us siblings liked that. From early on we all called him Guy, which when old enough, he made it official.

I believe that for a lot of Sanseis, third generation Japanese Americans, we didn’t often get comfortable opportunities to talk with our Nisei parents on a one-to-one basis until we became adults, but I would think that would also apply to most youths of all nationalities—a generation-gap-thing? For us Japanese American Sansei, little-by-little some of the hidden, almost taboo subject matters such as WWII, the evacuation and internment camps, and even personal family mysteries began to be revealed, such as: Why did we live in Denver in 1943? What was camp? How did Uncle Hiroshi die in camp? What is the meaning of my Japanese name?

This eventual learning mostly happened for me in the late ’80s when the push for redress and reparations was growing for America’s Japanese who had their civil rights violated by having been evicted from their homes and places of business, herded into holding (Assembly) camps, and then held in concentration camps for the WWII duration without the due process of justice; a gross violation of the U.S. Constitution. Eventually, thanks to strong efforts by Nisei and Sansei community activists and U. S. congressional leaders of Japanese heritage, the Civil Rights Act of 1988 was passed along with a Presidential apology and reparation of twenty-thousand dollars each for all who were directly affected.

Sadly, for those most deserving, the Issei and Nisei (first and second generation) who were elderly and passing away, too many of them who suffered the shame and hardship more directly missed out. All four of my grandparents, my father, and six out of eight uncles all missed out. This was the period when more Nisei began to open up about their WWII experiences and talking about their personal lives.

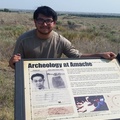

About this time I started research about what my father Sam Masami Ono did during WWII, one of the family mysteries. Regretfully I couldn’t talk to my father for he had already passed away in 1981 at the age of 68. I started talking with my mother, Kimiye (nee Okamura) shown in the Granada War Relocation Center, Amache, circa 1945.

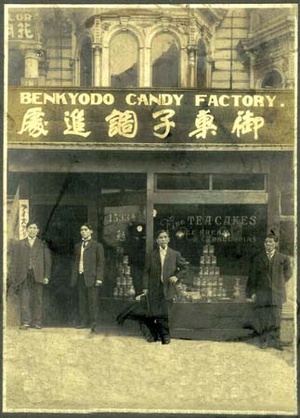

1531-1533 flats above Benkyodo, 1533-B Geary Street, San Francisco, ca 1906. Photograph courtesy of Rick and Bob Okamura, 3rd generation owner-operators of Benkyodo.

Besides my mother finally answering many questions about WWII and camp, she explained how she and my dad came up with my American and Japanese given name, Gary Tsutomu. “Tsutomu means studious.” She went on to say her father’s “confectionary company name was Benkyodo and ‘Benkyo’ means study as well.” Since I was born in the San Francisco Victorian flats above the first Benkyodo on Geary Street, they gave me the Tsutomu name. She even told me they thought that they might’ve called me Ben as a shortened nickname of Benkyodo!

As an Asian American youngster trying to fit-in in the 1950s and 1960s America, I do remember not wanting to be identified with being Japanese and keeping my Japanese foreign sounding name hidden. This was post-WWII, after all. I was never called Ben either, although that would’ve been more acceptable than Tsutomu! It was bad enough being teased about our last name. “Oh-No!”

My mother also went on to explain that they gave me the name Gary because I was born on Geary Street, but they felt that Gary was easier to pronounce and spell. By the way, all the houses are gone and Geary Street was widened to become the broad Geary Boulevard bordering San Francisco’s Nihonmachi, Japantown.

So, now that I’ve survived into my 70s, what’s in a name? You could even call me Ben if you wanted to or “Tootsie Roll,” a certain nickname if I had used my Tsutomu name!—Geary “Tootsie Roll” Ben Ono, I could live with that, or not! A rose, I’m not.

© 2014 Gary Ono