Read Part 1 >>

Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling

Over the 17 years that he practiced as an attorney, both in the Public Defender’s Office and in private practice, he recalls being one of very few Japanese American criminal defense attorneys.

“I did everything from drunk driving trials to death penalty trials. I wasn’t afraid. I would try anything. And so to me, to be able to be a criminal defense attorney was real important because it broke the stereotype of the quiet Asian,” Fujioka said.

Yet in being one of the few Japanese American criminal defense attorneys in the late 1970s, Fujioka could not easily shed the racial uniform cast onto him as a lawyer of Japanese descent.

And though the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 promised greater racial equality, racial prejudice was prevalent in the courtroom during Fujioka’s early career.

“First court I went into in East Los Angeles,” Fujioka recalled, “I was introduced to a judicial officer by Stan Shimotsu. The judicial officer did this sort of Groucho Marx kind of thing and he says, ‘Oh, it’s getting a little nippy in here.’ Well you could get removed as a judge if you say something like that now, but he said it to both of us because he knew nothing would happen to him because he was a white guy—and nothing did happen.”

Bringing Political Empowerment to the Asian American Community

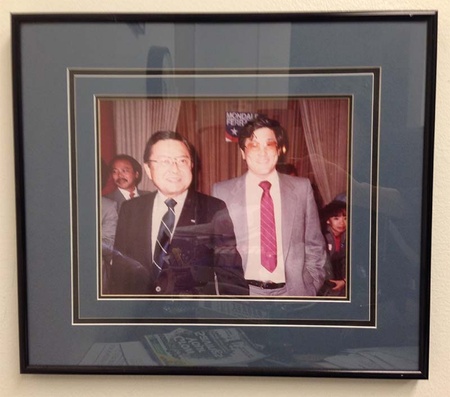

Alongside his career as a public defender and later a partner of a private law firm, Fujioka took on political fundraising as a means to empower the Asian American community.

In a nutshell, Fujioka explained, “I raised money, I helped people get access to politicians, and I helped make our voice heard.”

Over the years, Fujioka forged important political networks by organizing fundraisers for prominent Japanese American politicians such as the late Senator Daniel Inouye, the former Secretary of Transportation Norman Mineta, and the late Congressman Bob Matsui.

“You help them out [with fundraisers], and you knew that if something came up at the federal level or any other level, they’d make phone calls for us,” Fujioka explained.

In one particular instance, when the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) terrorized the Little Tokyo community with immigration sweeps, Fujioka recalled, “We called up Mineta, who called up Matsui, and they stopped it in 2 hours. They just threatened INS and told them, ‘If you do this, we are going to kill your budget.’ And it stopped—just like that. And it showed me the power of politics—that you could really get things done in a positive way.”

Looking back on the various fundraisers he organized over the years, Fujioka asserted, “I really liked doing it because at the same time I empowered the community, I felt empowered too.”

The Japanese American Bar Association

In 1989, Fujioka served as the president of the Japanese American Bar Association (JABA)—a professional network of Japanese Americans attorneys, judges, and law students committed to elevating the voice of the Japanese American legal community.

As the 13th president of JABA, Fujioka bore the responsibility of governing an organization that was formerly led by legal legends like Judge Edward Kakita and Judge Ernest M. Hiroshige.

Despite the gravity of the role, Fujioka did not recall encountering any major challenges over the course of his term.

“It was the greatest honor I ever had to be the president of JABA,” Fujioka affirmed, “because here is this organization that wanted nothing except to do the things that I wanted to do, and for every job we had, ten people would volunteer to do it.”

Speaking to his greatest accomplishment as president, Fujioka responded, “Just the fact that we were able to move from year to year…because if you exist then people have a thing to rally around when bad things happen. So your major job as president is to be the custodian that maybe moves it down the line a little bit but makes sure it’s in the same shape at the end of the year as it was in the beginning.”

Becoming the Judge of the Fujioka Family

After serving 6 years in the Public Defender’s office and 17 years in private practice, Fujioka was eventually appointed to the Los Angeles Superior Court by Governor Gray Davis in 2001.

Prior to his appointment, he could recall a time when “it wasn’t very conceivable that Asian Americans could become judges.”

However, he credits the leadership of the early JABA presidents for helping him conceive of becoming a judge.

According to Fujioka, JABA was initially organized with the goal of increasing Japanese American representation on the bench—a goal which met success with the appointment of Judge Edward Kakita, Justice Kathryn Doi Todd, Judge Jon Mayeda, and many other Japanese American lawyers by Governor Jerry Brown in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

“So once I saw that someone who looked like me could be a judge, I started thinking about it,” Fujioka explained.

As to why he wanted to become a judge at all, Fujioka credits his family’s wartime experience as a major impetus for seeking an appointment to the bench.

In line with his reasoning for becoming a lawyer, Fujioka looked towards judgeship as a means to empower the Japanese American community against any future violation of civil rights.

“My view is that it is important for us to be at all levels of society doing everything so that they don’t even think about relocation again,” Fujioka expressed. “We are you. Look in the mirror: we are judges; we are lawyers; we are doctors; we are cops; we are mayors of big cities—so just don’t even think about it. And that’s why I wanted to be a judge.”

Coming Full Circle

It has been 30 years since Judge Fujioka was an undergraduate working in East Los Angeles, and today, he is back working with troubled youth at the Sylmar Juvenile Courthouse.

“I am exactly where I wanted to be when I got out of law school, and back working with kids again,” he explained. “You can draw a straight line from my work in East Los Angeles to me becoming a judge 30 years later. Because when I was working for Casa Maravilla, I met Richard Polanco, who later became a State Senator, and he was instrumental in convincing Governor Davis to appoint me to the bench.”

Reflecting back on his career, he concluded, “Clearly, I’ve come full circle, I am working with kids again, and I never want to transfer out of Sylmar.”

Yet he also acknowledges that he is fulfilling a narrative that extends beyond his own aspirations.

Like himself, his father’s cousin once aspired to become an attorney, but he instead sacrificed his life on the battlefields of WWII for a country that had incarcerated his friends and family.

Prior to the sacrifices of the Nisei soldiers, “Americans couldn’t think that judges could look like me, lawyers that look like us, they couldn’t even think of Americans who looked like us,” Fujioka explained. “But those guys proved and showed to others what Americans look like, and that’s profound because without them doing what they did, I couldn’t be what I am now,” he said.

For that reason, “I really didn’t earn this job or pay for it,” he maintained. “It got paid for in blood before I was even born.”

To the Future Generation of Asian Americans

To the entire Asian American community, Fujioka underscores the importance of paying respect to the sacrifices that have been made on our behalf by supporting other communities in need.

“I have always known that the attorneys who represented my grandfather and my uncle, who resisted the draft, were Jewish and Irish,” Fujioka explained, “and that’s not a coincidence because those ethnic groups came out of a time when they had signs that read ‘No Irish Need to Apply’ because Irish weren’t even seen as white, and Jews have always had to deal with anti-Semitism in this country.”

“They put themselves at risk, and they lost clients because of what they did, but they did it anyway,” he applauded. “I revere those guys because they stood for the highest form of altruism and commitment to our Constitution.”

In support for future inter-racial solidarity, he urges, “I think we have to do the same thing now. If we take the position of, ‘We got ours, and you gotta get yours,’ then then we are no better than the people I used to criticize when I had nothing.”

Leaving a Legacy

Reflecting on his legacy as a Nikkei jurist, Judge Fujioka maintains a sense of humility: “I don’t think I will leave a legacy, but to the extent that anybody knows what I did, that I did a good job as a judge, that I was a good lawyer, and that I worked real hard to empower people who had no power.”

Empowerment has undoubtedly been the cornerstone of his entire narrative—starting with the empowerment of youth in East Los Angeles to the empowerment of the Japanese American legal community.

In fact, he continues his crusade for empowerment at his former high school in Montebello where he lectures the Advanced Placement (AP) Government class twice a year.

The message he leaves behind is this: “In a functioning democracy, it’s not the gods that lead us—it’s us. I am just like you; I sat in this classroom, but if I could do it, then anybody can do it, and you can do it too.”

© 2014 Sakura Kato