pil•grim•age

noun: pilgrimage; plural noun: pilgrimages

1. a pilgrim’s journey.

2. Synonyms: religious journey, religious expedition, haji, crusade, mission, “an annual pilgrimage to the Holy City”

3. a journey to a place associated with someone or something well known or respected “making a pilgrimage to the famous racing circuit”

4. life viewed as a journey “life’s pilgrimage”

The dictionary definition of pilgrimage refers to a journey taken for religious purpose, or at the very least to some place “respected.” Perhaps literature’s most famous pilgrimage is one that Geoffrey Chaucer wrote about in the 14th century’s The Canterbury Tales, when his characters embarked on a journey to the shrine of the martyred Saint Thomas Becket. Several centuries later, a pilgrimage became known as the sacred journey every Muslim adult was supposed to take at least once in a lifetime to Mecca, the birthplace of Muhammed.

The word camp also has several meanings. Merriam-Webster refers to a “place away from urban areas where tents or simple buildings are erected for shelter,” but it also defines camp as a place in the country for recreation or instruction, often during the summer. While the first definition applies loosely to America’s WWII concentration camps, the second has led to confusion among children who first heard about camp from their parents and thought it was a vacation spot—complete with tents, campfires, and S’mores.

When camp pilgrimages to Manzanar and Tule Lake began in 1969, they eschewed traditional definitions even though the first pilgrimage organizers, many Sansei, were most definitely on a crusade or mission. By going back to experience the dust, wind, and harsh weather conditions of the concentration camps that housed their parents and grandparents, organizers journeyed to not-so-revered places. Their destination was a place of ignominy, not a place of worship, and their gods were the Issei and Nisei, martyrs in many ways for being imprisoned 25 years earlier solely on the basis of race. Influenced by the social movements of the ’60s, Sansei organizers also inaugurated the journey as a precursor to the redress movement by calling attention to such things as the repeal of Title II of the Internal Security Act of 1950. Camp pilgrimages to Manzanar and Tule Lake have since led to more recent events at such former camps as Heart Mountain, Minidoka, and Poston.

As the oldest pilgrimage in Southern California, the Manzanar Pilgrimage has had a rich and storied history largely due to the work of the tirelessly dedicated Sue Embrey. Incarcerated at Manzanar, Embrey led the fight to designate the former concentration camp site as a California Historic Landmark in 1972, as a National Historic Landmark in 1985, and as a National Historic Site in 1992, which led to its becoming a national park. An interpretive center housed in the old Manzanar High School Auditorium was added in 2004, and visitors to the pilgrimage that year got a first look at the exhibition and camp tour that accompanied it.

The Manzanar Committee, now supported by Embrey’s son Bruce, among many others, continues to hold yearly pilgrimages on the last weekend in April. They continue to attract post-911 Muslim attendees as well as other ethnic and religious groups, including students and community supporters. In 2001, inspired by a program at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage, member Jenni Kuida introduced a program called Manzanar After Dark, an evening event designed for young people to learn from the firsthand camp experiences of the elders. It produced Keep It Going, Pass It On, Poetry Inspired by the Manzanar Pilgrimage, which includes these vivid recollections of what it is like to go on a Manzanar Pilgrimage:

Sometimes a howl, the winds of Manzanar

other times, just a whisper, keep the flames of truth burning bright.A far and desolate place, filled with memories

and spirits and strength and hope.

The Tule Lake Pilgrimage was Northern California’s early counterpart to Manzanar, and initially organized by Asian American Concern, a student group from the University of California at Davis. Following the first pilgrimage in 1969, the Tule Lake Committee was formed in 1978 to carry on the arduous work of planning a whole weekend of activities. The pilgrimage soon began attracting larger audiences, including Issei and Nisei, and arrangements were made to move the pilgrimage from the county fairgrounds—where participants slept in sleeping bags—to hotels in nearby Klamath Falls, Oregon, and more recently to the Oregon Institute of Technology (OIT).

Some “babies” born at Tule Lake. From left to right: Howard Nakamura, Ken Nomiyama, Fran Ellis, Helen Sakaishi, Satsuki Ina, Mitsuru Sakita, Tosh Nakano, Itsuo Yokota, Nancy Inouye Oda, and Judy Fukuman.

Today, camp pilgrimages continue to be a way of reconnecting to the past, but in the post-redress era, what began as largely political in nature—as a protest to the unjustness of camp—has by its very nature become a community bonding experience as well. Just as camp brought Japanese Americans together in a forced way, camp pilgrimages bring multi-generations and mixed races together in a voluntary way. While still calling attention to civil injustice, camp pilgrimages offer an opportunity for people with a common history and shared purpose to eagerly come together to learn in an atmosphere of open sharing. Old friendships are renewed and new acquaintances thrive through close contact with fellow pilgrims over several days of communing.

At the Tule Lake Pilgrimage, held every other year on the 4th of July weekend, participants are encouraged to travel by organized buses, a ride that can take anywhere from seven to nine hours, alongside fellow journeyers who begin and end their passage together. Once they arrive at the OIT where they are housed for three nights, partakers share tiny dorm rooms and communal bathrooms. The weekend includes a keynote address, intergenerational group discussions, panel presentations, film screenings, recreational activities, and entertainment—all designed to bring people together to share their life experiences, whether they were in camp or not.

A family that came from Michigan to hike Castle Rock at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage (2014). Pictured (from left to right): Marie Takemoto, Reiko Buckles, Judy Buckles, Jeanne Fujioka, and Tamiko Rehagen. Other family members attending were John Takemoto and Gil Fujioka.

The camp pilgrimage is oftentimes used for family vacations to learn about family histories in a place used to trigger memories. From ages 10 to 90, family members find ways to enjoy their time spent together—eating, sleeping, playing, and, most of all, talking. In addition, people are known to come from all parts of the country, from Seattle to New York, Torrance to Chicago, to get on buses bound for the Oregon border. This year, one Michigan family consisted of seven members—a brother and sister, their daughters and nieces, and included several spouses with no Japanese ancestry—enthusiastic to relate and to learn.

Taiko is usually a mainstay of camp pilgrimages. As a physical and spiritual embodiment of the resilience of the human spirit, taiko drums serve as a powerful call to attention. Taiko players capture the mood of the camp pilgrimage with their enthusiasm and energy, and attendees respond in kind with a unified show of community. The Tule Lake Pilgrimage is noted for its one-time performance of “Tule Lake Taiko,” its members joining together from several taiko groups to play together for a single rip-roaring concert.

Boston’s The Genki Spark taiko group spoke, performed, and led intergenerational discussion groups at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage (2014). From left to right: Trisha Kita-Mah, Karen Young, and Lee Ann Teylan.

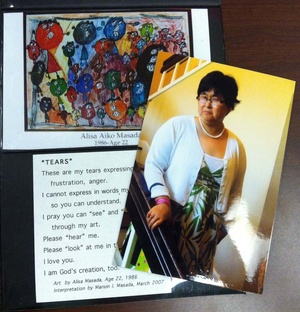

If there is an overlying theme to the camp pilgrimage, it is listening carefully to others’ stories. A Fresno minister and his wife, Rev. Saburo and Marion Masada traveling with their 54-year-old daughter Charise brought along a photo book featuring the art work of a second daughter, Alisa, who attended only in spirit. Alisa’s drawing, “Lollypop Ears,” illustrated this theme of hearing, healing, and understanding. Marion captured it beautifully in a poem she wrote to accompany the drawing by her special needs daughter:

Why the lollypop ears?

I haven’t stopped to really hear her,

To understand how she really feels.

That picture is a message to me

To listen with my heart and my ears

Then I won’t need lollypop ears!

Listening with “heart and ears” to what survivors went through more than seventy years ago brings many tears during a pilgrimage. At Tule Lake, the story of how countless incarcerees chose to give up their U.S. citizenship as a result of the insanity of their wartime imprisonment adds additional listening material to the heady discussions.

As fewer and fewer survivors remain, it becomes vital for these gatherings to record and preserve their stories. Camp pilgrimages serve as the necessary conduit for firsthand accounts to come out. They are a joyful reminder of the indomitable spirit of a group of people who rose above racial prejudice and civil injustice. As a model for other groups whose civil liberties are threatened, camp pilgrimages provide a heartwarming and indispensable way to “keep it going and pass it on.”

© 2014 Sharon Yamato