Most Nikkei immigrated to Canada between the 1890s and the 1920s, although the first Japanese in Canada was recorded in 1877. Early immigrants worked in the lumber and mining industries, fishery and agriculture in British Columbia. Japanese immigration peaked between 1905 and 1907, which exacerbated anti-Japanese racism.

The demand for Japanese exclusion led to the Hayashi-Lemieux “Gentlemen’s Agreement” of 1908, which reduced the yearly admission of Japanese laborers to four hundred. Subsequent years saw the influx of “picture brides” since the immediate family members of Nikkei residents were still allowed to immigrate to Canada. However, by 1928 Japanese immigration was limited to 150 per annum.

Japanese prospective brides on board a ship, ca. 1905. (Collection of Japanese Canadian National Museum [97/200a-b])

Canadian Internment

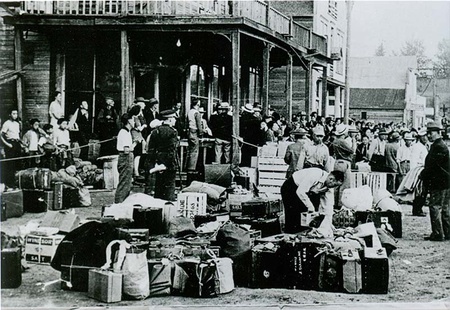

The emergence of families stabilized the community, but the Pacific War destroyed its foundation. The confiscation of properties and the internment of Nikkei in inland concentration camps soon followed. Under the War Measures Act, the internees, most of whom were Canadian citizens, were forced to either move permanently to the east or renounce citizenship and leave for Japan after the war. Until 1949, Japanese Canadians were not able to return to British Columbia or fully regain their civil rights.

Second uprooting more than four thousand Japanese Canadians who were exiled to Japan after World War II, Slocan, B.C., ca. 1946. (Collection of Japanese Canadian National Museum [94/76.015a-c])

Post-World War II and Redress

The postwar years saw the rapid integration of Japanese Canadians into mainstream society. Most lived in Toronto and Vancouver, were highly educated, and had married non-Japanese spouses.

The redress movement for the wartime internment and its eventual success in 1988 offered a common cause for the Canadian Nikkei to unite. Today, the Nikkei community has witnessed an unprecedented creation of community infrastructure and networks despite its internal diversity.

The signing of the redress agreement: (seated) Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Art Miki; (standing, from left to right) Don Rosenbloom (lawyer), Roger Obata, Hon. Lucien Bouchard (Secretary of State), Audrey Kobayashi, Hon. Gerry Weiner (Minister of Multiculturalism), Maryka Omatsu, and Roy Miki, Otawa, Ontario, September 22, 1988. (Photograph by Gordon King. Collection of the Japanese Canadian National Museum [94/64.5.001a-b])

Source:

Akemi Kikumura-Yano, ed., Encyclopedia of Japanese Descendants in the Americas: An Illustrated History of the Nikkei (Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press, 2002), 149.

* Developed in collaboration with the Japanese Canadian National Museum.

© 2002 Japanese American National Museum