Background of Japanese Overseas Migration

The overseas migration of Japanese started with the opening of the island nation to the rest of the world and its entry into modernity in 1868. Becoming a part of the international network of labor, capital, and transportation, the Japanese suddenly found themselves in the middle of rapid socio-economic change, thereby creating a rural population ready for domestic and international migration.

Beginnings of Overseas Migration

Kona men in sugar cane field of Hawai'i, date unknown. (Gift of Sukeji Yamagata. Courtesy of the Rev. Shugen Komagata. Japanese American National Museum [95.197.25])

In 1868, an American businessman sent a group of approximately 148 Japanese to Hawai‘i to work on sugar plantations and another 40 people to Guam. This unauthorized recruitment and shipment of laborers, known as the gannen-mono, marked the beginning of Japanese labor migration overseas. However, for the next two decades the Meiji government disallowed the departure of emigrants due to the slave-like treatment that the first Japanese migrants received in Hawai‘i and Guam. Instead of going abroad, many people were involved in the development of Hokkaido, Japan’s northern-most island.

It was not until 1885 that the massive emigration of Japanese began. In that year, the governments of Japan and Hawai‘i concluded the Immigration Convention under which approximately 29,000 Japanese traveled to Hawai‘i for the next nine years to work on sugar plantations under three-year contracts. In the meantime, thousands of Japanese departed for Thursday Island, New Caledonia, Australia, Fiji, and other South Pacific destinations for similar contract work. Starting in 1903, contract laborers also went to the Philippines, where they were involved in the construction of a major highway. Other Southeast Asian regions attracted Japanese laborers and business people as well. In essence, most of these “immigrants” were not settlers, but they were dekasegi laborers planning to return home with money after a few years of work in a foreign land. In order to regulate the activities of emigration companies and to protect the interests of emigrants, the Japanese government enacted the Emigrant Protection Act in 1896.

Colonization

In 1893, a group of Japanese government officials, politicians, and intellectuals organized the Colonization Society, calling for the overseas development of Japanese “colonies.” Like other modern nation-states, they argued that Meiji Japan would need to expand externally, in order to obtain larger markets to export its “surplus” population and commercial goods. The Society’s pet project of 1897 attempted to establish an agricultural colony in Mexico. It did not succeed, but it marked the beginning of Japanese emigration to Latin America, followed by the departure of 790 people to Peru for contract work in 1899.

The farm managed by Compañia Japonesa Mexicana Sociedad Cooperativa (Nichiboku Kyodo Kaisha), founded in 1905. Ryojiro Terui (far right), the man holding child, is one of the leaders, ca 1910. (Collection of Asociación México Japonesa, A.C.)

Exodus to North America

Around the turn of the century, many young men left Japan to get an education in the United States, for the opportunities in Japan were limited. Some were fortunate to get funding to go to prestigious universities on the East Coast, but most congregated in cities like San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle. Often known as “school boys,” they attended school while performing domestic work in exchange for room and board from white families. Meanwhile, there were many common laborers who entered along the Pacific Coast, both in the United States and Canada. Japanese immigration to the United States became a political problem during the 1900s. Anti-Japanese agitation on the West Coast eventually led to the termination of Japanese immigration to the United States in 1924 and the severe restriction of Japanese entry to Canada in 1928.

To Latin America and Beyond

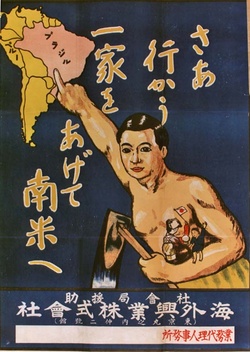

A recruitment poster promoting Japanese emigration to South America, ca. 1925. Recruitment was conducted by the Overseas Development Company (Kaigai Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha), established in 1917 to cope with the severe restrictions imposed on Foreign Affairs Diplomatic Record Office)

With North America shutting its doors to people from Japan, other countries and areas absorbed the growing numbers of Japanese immigrants. Brazil became the main destination. In 1908, the first group of Japanese left for Brazil as Japan voluntarily restricted the issuance of passports to new labor immigrants for the United States and Canada. In 1925, the government started to subsidize the transportation of Brazil-bound emigration. Four years later, Japan established the Ministry of Colonial Affairs (Takumusho), which offered “guidance” for Japanese residents in countries other than North America and Europe.

Meanwhile, Imperial Japan had steadily acquired colonial territories in the surrounding regions and Micronesia after a series of foreign wars, including World War I. Taiwan became a formal colony in 1895 after Japan’s victory over China, while Korea was officially annexed in 1910 as a result of the Russo-Japanese War. Japan took over Micronesia from Germany in 1914, which later became a Japanese mandate entrusted by the League of Nations. These regions, combined with portions of Manchuria and Sakhalin, became a locus of “Japanese development” where tens of thousands of “immigrants” settled and displaced local populations. Though many of these so-called “immigrants” shared similar socio-economic backgrounds with their counterparts in the Americas, the former group was essentially colonizers protected by the military power of Japan, whereas the latter tended to become targets of social and legal discrimination in “host countries.”

State-sponsored Emigration and Anti-Japanese Containment

In the mid-1930s, after the establishment of a puppet government in Manchuria, Japan officially made overseas emigration part of its colonialist policy. Previously, except for the government-contract labor migration to Hawai‘i and the travel subsidy for emigrants to South America, the Japanese government was not directly involved in the recruitment and management of emigrants. Instead, emigration companies played a central role in the departure of many Japanese emigrants, while others left the country on their own. The colonization of Manchuria in the 1930s, however, involved the state-sponsored emigration of impoverished farm families from Central and Northern Japan to this region. Although the Pacific War stopped Japanese migration to the Americas, other areas like Micronesia, Manchuria, and Japan’s colonial and newly occupied territories drew a large number of Japanese until the end of World War II.

Pacific War and Massive Return Migration

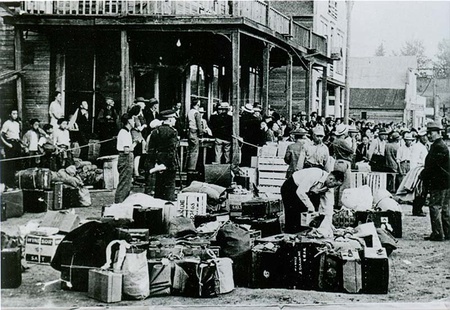

After the war, there was a massive reverse migration of former colonial settlers, soldiers, and repatriates back to Japan, which involved tragedies of family separation, starvation, and death. Many children were left in Manchuria, Micronesia, the Philippines, and other Asian regions, where some were taken in by local people. At the same time, the Japanese who remained in the “host countries” also had to start over after forced removal, incarceration, and/or severe restrictions on daily activities.

Second uprooting of more than 4000 Japanese Canadians who were exiled to Japan after world War II, Slocan, B.C., ca. 1946. (Collection of Japanese Canadian National Museum [94/76.015a-c])

Postwar Resumption of Overseas Migration

War-devastated Japan needed to disperse its growing population that exceeded the domestic supply of food and other limited resources. During the Allied Occupation, no emigration was allowed with the exception of so-called “war brides,” who entered the United States, Canada, and Australia, among other nations, with their non-Japanese husbands. Yet, after the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951 that granted Japan independence, the country made special arrangements with Latin American governments to send emigrant settlers for agricultural development.

The first post-war emigrants left for Brazil in 1952, Paraguay in 1954, Argentina in 1955, Dominican Republic in 1956, and Bolivia in 1957. The Foreign Ministry was first responsible for the administrative processes of post-war emigration, which was later taken over by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. The United States also attracted many after repealing its ban on the entry of Japanese, first allocating an annual national quota of 185 immigrants in 1952 then abolishing restrictions based on national origin in 1965.

A New Phase

By the 1970s, however, the economic recovery of Japan stemmed large-scale emigration of Japanese. Ironically, since the mid-1980s, many second and third generation Nikkei have come from Latin American countries to Japan, where they could earn much better wages than in their economically-troubled homelands. In 1990, the Japanese government amended its immigration law which enabled a person of Japanese ancestry to legally stay in Japan for work. According to a 1990 official estimation, Nikkei in Japan numbered 61,000 Brazilians, 7,500 Peruvians, 6,400 Argentines, 650 Paraguayans, and 600 Bolivians.

Though the era of mass emigration is over, many Japanese still leave Japan to live all over the world because of temporary work assignments, marriages, education, or business ventures. New Japanese communities are thus emerging in Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania. In 1993, there was a total of 1,650,285 Nikkei and Japanese permanent residents in countries other than Japan. Among them, 816,034 resided in North America, while 737,642 lived in Latin America. Asia had a population of 58,395; Europe 21,179; Oceania 16,235; and Africa and Near East 796. Wherever they have settled, the Nikkei have established communities and contributed to the development of unique histories and cultures in the countries they call their home.

Brazilian dekasegi taking part in Carnival festival in Kobe, Japan, 1997. (Photograph by Internal press. Collection of Museu Histórico da Imigração Japonesa no Brasil)

Sources:

Eiichiro Azuma, “Brief Historical Overview of Japanese Emigration. 1868-1998,” report to The Nippon Foundation, Japanese American National Museum, Essay in “International Nikkei Research Project: First-Year Report, April 1, 1998 to March 31, 1999” (1999), 6-8.

Akemi Kikumura-Yano, ed. Encyclopedia of Japanese Descendants in the Americas: An Illustrated History of the Nikkei. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press, 2002.

© 1999 Japanese American National Museum