Read part 1 >>

As the Japanese and Japanese American population grew, generational differences emerged. For example, in four years between 1926-1930, the percentage of Nisei households among the larger Japanese population increased from 26.7 percent to nearly 50 percent. As a result, by the 1930s, with a rising Nisei generation, Rafu Shimpo began to also print English portions of their daily. The Los Angeles daily was not shy in its endorsement of baseball for Japanese Americans. The Nisei generation showed little interest in traditional Japanese sports like Kendo or Judo, the paper reflected, “[r]ather we should prompt them to take up whatever sports they like. Baseball it is!” The Los Angeles Nippons figured prominently in the paper as few other Japanese American teams received the amount of coverage bestowed upon the local team.1

Around Los Angeles, teams played at public facilities such as Griffith Park, which in the late 1920s remained a rural area just north of the city. Additionally, Japanese Americans built new fields, often within the vicinity of foreign language schools, in places like San Fernando Valley. This required no small sacrifice from the Japanese themselves. “They may have been poor farmers,” acknowledged writer Wayne Maeda, “but when it came to donate money for uniforms and equipment, they reached down into their pockets and always came up with something to help the team out.”2

Part of the game’s utility lay in its appeal across generations. “Baseball allowed each generation to interpret the meaning of the sport,” noted Maeda. Issei saw it as a means to connect their American-born children with Japanese culture, and believed it emphasized Japanese values of loyalty, honor, and courage. In contrast, Nisei saw the sport as more modern than Kendo or Judo; it also provided an expression of their patriotism to the United States. Both believed the sport would serve as testament to their dedication to American ideals. In this context, baseball became a “safety net from the outside and allowed [Japanese Americans] to demonstrate their cultural traits before an audience of their own,” argues Regalado. For parents, simpler explanations also existed: it kept their kids out of trouble as more than a few older Issei worried about their children boozing, drugging, or gambling their lives away in American environs.3

Japanese Americans’ place in Japanese society also became an issue. As a result of being in America, some Issei and Nisei worried about their status among Japanese nationals in Japan, believing that their more tenuous connection to their ancestral homeland might make them less than equals in the eyes of some Japanese. Baseball enabled the Issei and Nisei to assert their equality with their counterparts living in Japan.

Baseball helped to promote transnational interactions so common today in baseball, soccer, basketball, and other sports. In 1931, the Nippons traveled to Japan, where they barnstormed across the islands and, according to catcher Ken Matsumoto, established “the best record of all teams that have invaded Japan.” When a team of American All-Stars including Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth toured Japan in 1934, they inspired near riots. On November 2, 1934, historians estimate that nearly 500,000 Japanese attended the team’s informal parade up the Ginza (Tokyo’s Broadway). When the Tokyo Giants returned the favor by coming stateside in 1935, the three-game series with the Nippons drew crowds as large as 5,000. In the end, the Nippons could lay claim to being the best Japanese American side, encountered by their Japanese rival.

Due to the aforementioned generational change, transportation innovations that enabled for travel abroad and within the U.S., and the sport’s malleability among Nisei and Issei, the 1930s represent the high water mark of Japanese American baseball, particularly in California. By 1930, 70% of America’s Japanese population resided in the state. This period coincided with the creation of Los Angeles Nisei Week in 1934, which attempted to draw Japanese Americans back to Little Tokyo, while also demonstrating a connection to American cultural activities in “their own ethnic context,” points out Regalado. Similarly, in 1936, Northern California communities started the first July 4th tourney, a clear attempt to display attachment of American traditions and ideals.

Tragically, none of this helped in the wake of Pearl Harbor and the simmering racism of WWII California. The “White California” movement of the early twentieth century stemmed from a “racism of envy,” notes Starr, and it persisted through WWII as some white farmers resented Japanese and Japanese American agricultural acumen. Moreover, unlike Americans of European descent, notes Regalado, Japanese American guilt for the war was viewed as collective. Though government studies like the Munson Report upheld Japanese American loyalty and pointed out the racism of anti-Japanese rhetoric, U.S. officials forced Nisei and Issei into concentration camps.4 Only Nisei old enough for military service escaped internment.

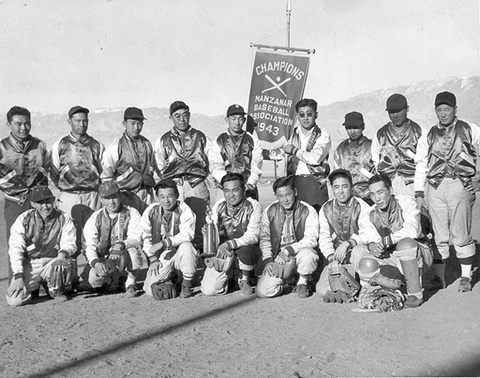

In the camps, baseball provided an outlet for the trauma of incarceration. White WRA administrators provided very little for internees, with a dearth of recreational facilities and equipment, Issei and Nisei created their own. Baseball once again took center stage. At the Merced County Fairgrounds, internees transformed an empty landscape into a diamond though the surroundings remained sparse. “We had to make the baseball diamond, and there were no stands, no seats, no nothing, so the crowd just stood around the field and watched the game,” remembers internee and baseball standout, Fred Kishi. Camp newspapers devoted nearly as much coverage to baseball as to those Nisei serving on the front. Far from inconsequential or frivolous, baseball occupied an essential place in internee life.5

Still, baseball could not settle intraethnic disputes. Organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League, who helped administrate the camps in an attempt to improve conditions and demonstrate continued loyalty to the United States, came to be seen by some as collaborators. Some of baseball’s Japanese American proponents were viewed in like terms. James Sakamoto, the publisher of Seattle’s Japanese American Courier, endured such criticism after internment and died, as Regalado describes him, “a broken man.”

Others, like Fresno’s Kenichi Zenimura, who embraced interracial play and took teams abroad to Korea, Manchuria, and Japan in an effort to promote peaceful international relations, faced residual discrimination from whites. Zenimura returned to Fresno and reestablished local teams, but continued to encounter racism. One of Zenimura’s players, Dan Takeuchi, recalled enduring racist taunts from white fans; he and his teammates toughed it out in order to “let others know we were going to go on very positively.”6

Still, bright spots surfaced as well. South Pasadena native Jackie Robinson grew up playing sandlot ball with Japanese Americans from local enclaves. At Pasadena Junior College, Shig Takayama played with Robinson and the two roomed together, often experiencing the effects of segregation together. In 1975, Ryan Kurosaki became the first Japanese American player to reach the pros when signed by the St. Louis Cardinals as a reliever. Lenn Sakata followed for the Milwaukee Brewers two years later.

Internment had robbed many of the best Japanese American players any opportunity to compete at the professional level. Talented players like Fred Kishi joined the military during the war, thereby eluding internment, but missing any possible window for a professional career in baseball. While Japanese nationals eventually became a common sight in Major League Baseball, facilitated no doubt by these earlier transnational connections, their American counterparts failed to achieve such success.7

Nonetheless, the number of professional Japanese American baseball players remains beside the point. Baseball shaped Japanese American identities, stitched together communities and generations, and provided solace to a people traumatized by unjust incarceration. If the journey matters as much as the destination, baseball took Japanese Americans across oceans and cultures while rooting them more firmly in Southern California on their own terms.

Notes:

1. Kevin Starr, California: A History, pgs. 300-301.

2. Samuel Regalado,Nikkei Baseball, 2013.

3. Ibid.

4. Michi Nishiura Weglyn, “The Secret Munson Report”, in Asian American Studies: A Critical Reader, Eds. Jean Yu-We Shen Wu and Thomas C. Chen, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010).

5. Samuel Regalado,Nikkei Baseball, 2013.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

*This article was originally published on KCET’s website on January 10, 2014.

© 2014 KCET; Ryan Reft