“In the heart of every human being there is a quest for truth, a quest for justice, a quest for peace, a quest for love, a quest for mercy. In the heart of each one of us, we have this longing for something over and above our immediate reality.”

For Masako Kimura Streling, this truth appears to have been a driving force throughout her life, even before she had fully realized it.

Yes, Masako is the eldest daughter of a large Okinawan family and descendant of a samurai clan, had a successful career with Japan Airlines before earning her Bachelor’s degree in Theology and a Master’s degree in Pastoral Studies from Loyola University Chicago, served as a Lay Missionary to a priestless Catholic church in Japan, and now happily lives with her husband of over 60 wonderful years in beautiful southern California. Just becoming familiar with these bullet points, however, would be grossly insufficient to understand her true strength of character and ever-resilient spirit.

Likewise, I would caution Discover Nikkei readers and JANM goers against prematurely judging or generalizing Masako’s book, I Thought the Sun Was God, as simply a missionary memoir without much value beyond its religious overtones. The Museum’s public program on Masako’s book has come and gone, but I wanted to revisit her important story and encourage many of you to put aside any preconceived notions you may have, based on its title or anything else, and just delve right into its pages.

This article is not a book report so I will not spend the remainder of it recounting her compelling anecdotes and deeply-held convictions. Rather, readers are encouraged to lose themselves in her many shared narratives in Sun, sympathize with Masako’s struggles, and rejoice in her triumphs, through her own words. True, her book may discuss topics that vary from the typical themes to which some of us may have grown accustomed to exploring through the Museum’s series of author/filmmaker meet-and-greets, but Sun is about so much more than its religious context.

Aside from her book imparting a great Japanese history lesson into the less-spoken side of the Okinawa/mainland Japan backstory, Masako also adeptly portrays life of a Japanese immigrant in post-WWII America in somewhere other than California (Midwest). This is not an all-together common perspective we see roll through the Museum bookstore. For this reason, I appreciate that Masako shares some of the darker periods of her past so that we can better understand the times.

If one were to, literally, judge this book by its cover, sure, a likely conclusion to be drawn is that this book is foremost about religion. If one were, however, to move past the cover as I did, it is just as likely that one might conclude this book to be a testament of an individual, not merely accepting, but learning over time, to love her life…embracing the totality of her life circumstances…no longer wholly regretting or lamenting the negative experiences in her life, but rather learning to appreciate them as opportunities for growth as a person.

Taking a closer look at Masako’s entire title (in small print), she refers to spirituality. I make the following statement, as a Christian myself and with the utmost respect for those of other religions faiths: spirituality does not necessarily have to equate with religion and vice versa.

It is with this understanding that I took away the first of two overriding messages from Masako’s enlightening book: whatever triggers a personal revelation or a newfound outlook on life, embrace it and make the most of it! Some might view it as a new lease on life, figuratively speaking. Of course, in some cases like Masako’s battle and defeat of cancer, this new outlook or revelation may result from something all too horrifyingly real. For Masako, the trigger was Jesus Christ. In others, it may be something or somebody else. As I see it, it does not matter what the trigger is, if it allows that person to make sense of seemingly disparate or negative experiences in their life, and it can help them become a better person, run with it!

This leads me to the second of two overriding messages that I took away from Sun. Whether a trigger is required or whether a person can will her-or-himself toward this goal, we should all love our neighbors as ourselves; treat others as you would want to be treated. Despite perhaps more current, hot button topics consuming the headlines, this is still the central tenet of Jesus Christ’s teachings. I propose, however, that this is an excellent rule to live by, regardless of whether one believes in God.

Masako testifies of Jesus Christ; she wants to let her readers know of His significance in her life and, she believes, in all of our lives. She is a devout Christian and served a worthy mission, so this is inevitable. Moreover, her lifelong journey of self-discovery—forgiving others and herself, recognizing she is a woman created in God’s image—necessarily takes us through her firsthand experiences, of which some are religious. (Although one would have to read well over 100 pages into her book before Masako’s religion becomes the dominant topic.)

People, however, can gain truthful perspectives like the two I have mentioned above without religious overtones. Readers who share her faith will naturally find commonalities in her stories; but as I see it, whether a person considers themselves religious should have no bearing on whether this book is worth reading, or whether a person can glean something from Masako’s life story that she has so thoughtfully laid out for us. The resounding answer is, yes, everybody can learn from Masako’s life lessons.

Through all her hardships—growing up a woman in a patriarchal society, surviving as a Japanese woman in post-WWII America, serving as an unrecognized Lay Missionary with her husband, and overcoming her various physical ailments in her later years—Masako’s resilient spirit shown through time and time again.

Masako grew up in what is now known as Okinawa. Her mother was Okinawan and her father’s family descended from the same samurai clan whose final stand (Satsuma Rebellion) inspired the Hollywood blockbuster, The Last Samurai. In her book, Masako describes at length what it was like sacrificing as the eldest daughter in a large family, dealing with Japanese prejudices against Okinawans, and overcoming the staunchly patriarchal Japanese society. Regarding the latter, Masako recollected the following:

“[M]y father lamented my birth because the society of Japan did not value the life of a female child. …When I was growing up, I was told that my place as a woman was always to be subservient to the male gender and always be smart, tactful, and considerate in assisting them. Considerate meant that when I was asked by my grandfather or father—or even my elder brother—for an ashtray, I would be smart enough to also bring a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches. I was taught never to butt in when my grandfather or other men were talking. I learned not to listen, see, or talk when I was not asked to do so in the presence of men.”

Fast forward to after WWII. Masako married a U.S. soldier. Eventually, she bravely left behind everything and everyone she had ever known to cross the Pacific Ocean to join her husband in America. Unfortunately, for Masako, the loneliness she felt on the S.S. President Wilson on her way to San Francisco continued as she looked for meaningful and equal employment opportunities. At one point, she courageously wrote an editorial piece to her local newspaper titled, “Japanese War Brides Ask for Better Opportunities.” In it, she unapologetically stated her case as to why she deserved better employment opportunities. Very gutsy.

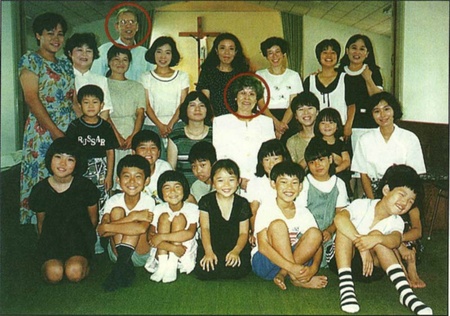

After finding success as a career woman at, among other companies, Japan Airlines, Masako found herself in college at Loyola University Chicago. Her associations in college led her to serve a three-year mission as a Lay Missionary for the Catholic Church in Japan (specifically, a rural Kainan church). Not surprisingly, a big portion of Masako’s book is devoted to her missionary years as well as the events surrounding her mission. For various reasons, Masako and her husband Carl were treated as second-class citizens by the Church during their mission. Again, Masako’s fighting spirit defended her and her husband’s honor in an impassioned speech at a monthly Osaka Diocesan meeting, in front of two hundred-fifty priests. To her credit, when she had finished speaking, “almost all of the Osaka Diocesan priests lined up and asked for [her] forgiveness, or expressed their sorrow.”

Still, Masako’s status as a Lay Missionary was never officially recognized. In fact, toward the end of her three-year mission, she attended a Pentecost Workshop at the Franciscan Retreat House in Totsuka, Yokohama. While taking a stroll one morning, she ran into a Father who asked her for her name and capacity. When she told him she was a Lay Missionary, the Father “took out a pocket-sized green book and flipped through it, saying he could not find [her] name or [her] husband Carl’s name in his green book.” Masako “felt defeated and crushed after finding out there existed a green book known as the Columban Fathers Directory, and, that [their] names were not listed within it.”

She further reflected thusly: “We later discovered that no matter where you search in the Columban Society in Japan, there is absolutely no record of our names. …Being treated in this manner by our brothers and leaders in the Holy Order was humiliating and hurtful.”

These deep-seeded emotions stayed with Masako for years, so much so that she believes it affected her health as she grew older: lower back fusions, neck spinal fusions, rotator cuff repairs, hysterectomy, and colon cancer.

It was not until this latest series of health-related hardships that she fully realized Jesus Christ’s role in her life. By truly allowing the Atoning power of Jesus Christ to heal her, she learned to forgive those who hurt her so much during her mission. In Masako’s own words, “I am grateful for a merciful God who has allowed me to experience the mystery of suffering in the Kainan experience; and, in my life as a child and young adult in a world of persistent violations of sexism. God vindicated all these sufferings, humiliations, and the pain of loneliness. Without these experiences and the creative and freeing power of God, I would not have become the person I am today.”

Ultimately, what makes me smile the most is that Masako came to realize that she no longer needed her name to be printed in a little green book to be validated.

As I mentioned at the beginning, the Museum has already hosted a book discussion with Masako Kimura Streling for her book, I Thought the Sun was God, but I still encourage readers to consider picking up a copy either through Amazon or Friesen Press. If you have been struggling to make sense of peculiar events in your life or if you want to reassess the meaning of your life from a different perspective, this book just may do the trick.

© 2014 Japanese American National Museum