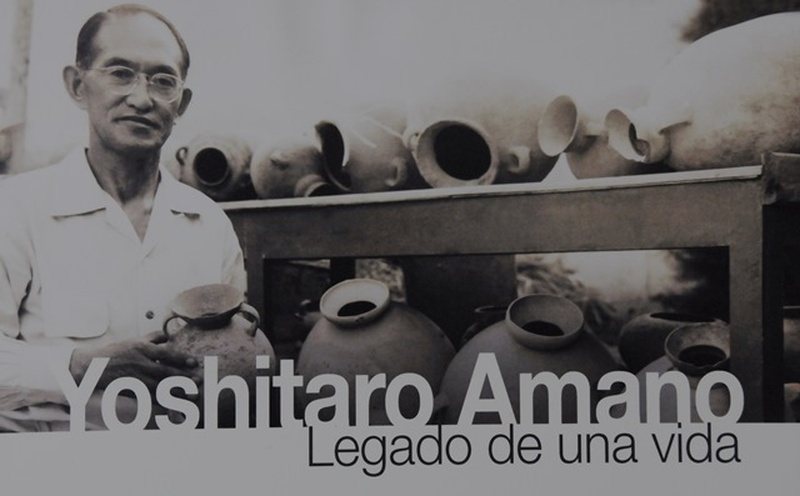

If a filmmaker had to direct a film inspired by the life of Yoshitaro Amano, he wouldn't have to invent or exaggerate anything to give it emotion. His life had all the ingredients to be an event on the big screen: adventure, drama, passion, fight, etc. There would be plenty of scenarios: a hacienda in Chile, a commercial house in Panama, a concentration camp in the United States, a port in Africa, a museum in Peru. And his native Japan, of course.

Amano was a naval engineer, businessman, researcher, globetrotter and philanthropist. They accused him of being a spy. He survived a shipwreck. She ran away with Emperor Hirohito's younger brother. He revalued an ignored culture.

BUSINESS IN THE AMERICAS

Yoshitaro Amano arrived in Peru for the first time in 1929, although only as a transit destination. Ours was one of the nine American countries in which it did business at that time (the others were the United States, Panama, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Bolivia).

(Photo: © Amano Family Archive)

In 1935 he visited Machu Picchu, becoming – maintains his son Mario – the first Japanese to visit it. In 1951 he set foot on Peruvian soil again, but this time not to leave again.

Between one trip and another, an event changed his life: the Second World War. A Japanese man who had his own tuna boat and companies in the three Americas was a very visible target for the United States, which in December 1941 captured him in Panama. During the war, the Japanese in this part of the world were suspect, especially if they had economic power.

He was interned for about a year and a half in concentration camps in Panama and the United States. In June 1943, he was put on a ship that took him to the city of Lourenço Marques (today Maputo), in Mozambique, where he was part of a prisoner exchange. There they shipped him to Japan and in August he was already in his country.

Without business and expelled as an enemy of war by the US, perhaps someone else would have chosen to stay in their homeland and not complicate their lives by setting sail again to cross the ocean. But he, a tenacious adventurer, chose the difficult path.

In February 1951, he boarded a Swedish ship in Yokohama to travel to America. The boat capsized on a storm-hit night, but – fortunately – its passengers were rescued by an American ship that took them back to Japan.

The bad experience did not deter him. In March he embarked again. In April he arrived in Peru after an eventful journey that included Canada, Panama (where he was saved from being captured for the second time thanks to a police chief who was the son of a former employee of his company), Jamaica and the Bahamas before setting foot in Lima, where he It was difficult to enter due to lack of documents.

In Peru Amano began a new life, less restless, but more fruitful in the cultural aspect and, especially, beneficial for our country.

RESCUING CHANCAY

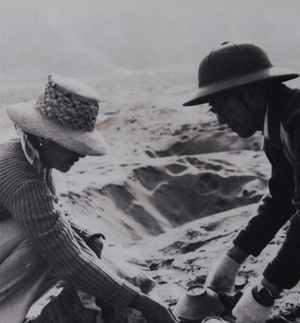

In the 1950s, Yoshitaro Amano became a regular presence in Chancay (north of Lima), where he collected archaeological pieces of the culture that settled in that part of the country in the year 1200. The area was not virgin, since the Looters had desecrated it. However, they only took the metal objects, discarding the textiles.

The huaqueros considered Amano as an extravagant Japanese who was even willing to pay for some looms that they burned to keep warm while huaqueros. They were very valuable to him. “Threads have woven the world,” he used to say.

Ceramics were also despised. The children of the local landowners used them to play target shooting with their shotguns. In general, the Chancay culture was little valued.

Amano's image could hardly go unnoticed in the area. His son Mario describes the clothing that distinguished his father: “Safari helmet, white shirt, jacket and tie, white gloves, baggy pants and high boots. A look that sums up as “archaeologist mixed with safari.”

A chance meeting was decisive in forming his collection of archaeological pieces. One day, while exploring, he arrived at the Huando hacienda, in Huaral, and found a pre-Hispanic cemetery transformed into a garbage dump. Excited, he began to poke around. Suddenly, the landowner Graña appeared. “What are you doing there?” he asked. “I'm looking for scraps of textiles,” he replied.

Graña took him to the Palpa hacienda, property of the Vizquerra family, which owned mantles. They, in turn, took him to the inn of a Japanese man named Ishiki.

The Japanese recognized Amano, as he had attended a conference that Amano gave shortly after his arrival in Peru to inform the Japanese colony of the situation in Japan after the Second World War. The event aroused great interest in the community, eager for news.

Ishiki was a leader of the kachi-gumi (Japanese who refused to accept their country's defeat in the war) in the area, so someone like Amano, who denied what they preached, was frowned upon.

However, Amano managed to befriend Ishiki. He, aware of her interest in archaeological remains, showed her his warehouse full of ceramics and textiles.

How did Ishiki come to have his own “collection”? For their huaquero clients. Since ceramics and textiles have no value, they thought, they should at least be used to exchange them for food at the inn.

Amano proposed to buy the pieces from him. “If you take it all, I'll give it to you, you're getting in my way,” Ishiki told him. When word spread, the friends of the owner of the inn who also had pre-Columbian pieces gave them to Yoshitaro, happy as if Borges had been given a library.

Mario remembers that his father enjoyed showing off his extensive collection. His friends arrived first. Later, the friends of his friends. Its fame grew so much that in 1958 Prince Mikasa, brother of the then Emperor Hirohito, visited the Amano residence to admire the collection during his visit to Peru, a huge event at the time.

Mikasa slipped away from her official schedule to disappear with Amano, reveals her widow Rosa. “My husband and I came to the house. The prince was very happy seeing everything, when the police came. My husband received a shock, (they told him) 'you can't escape by keeping quiet.' The prince wanted to come. That's why I say, Prince Mikasa visited my house,” he says, laughing.

More than half a century has passed since that visit, but the memory remains intact in the memory of Rosa, a woman with soft manners who gets emotional when she evokes Amano. “I'm nervous, I haven't talked about my husband in a while,” she confesses.

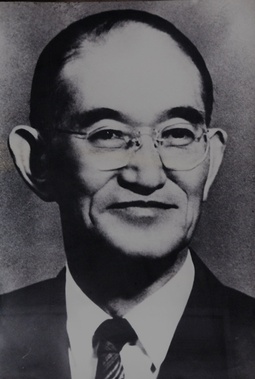

“He was an extraordinary person. He became a man alone,” he says. “He was very studious, very benevolent with people, very kind; a great intellectual, he knew many things,” he adds. His son Mario corroborates: “He was very serious, very upright and very cultured, so much so that it was boring. “He knew a lot, he knew everything.”

Why did Amano choose Peru to put down roots? “Because of archaeology,” Rosa answers. Mario, for his part, says that his father said that nowhere in the world could ancient objects be rescued so easily, without the need to excavate because they were on the surface, as in Peru. And he remembers him as a tireless traveler: “He really liked going to the mountains. “He loved Peru.”

(Photo: ©APJ / José Chuquiure)

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 88, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2014 Texto: Asociación Peruano Japonesa; © 2014 Fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa / Archivo Familia Amano