Who among us Nikkei has ever wondered about whether our lives might have been ‘better’ had we been raised, educated and worked in Japan?

After I went to teach there in 1995, I started to question whether I could actually live in Japan permanently. To my mind, the lifestyle was preferable in many ways (e.g., teachers are respected, great public transportation, food, the splendid manners of the populace). However, when it came to career related issues, then there was no question that I had to get back to Canada. Without doing so, issues like having a pension and other security to fall back on when I retired would be in jeopardy. We, even if we are Nikkei, are guests who are not expected to overstay our welcome.

For many though, Japan becomes an adopted home where many have chosen to live into old age. Some who were lucky enough to be in Japan during the golden years of the Bubble Economy and fantastic salaries, are close to retiring with wonderful retirement packages. However, those days are long gone.

As those of us who have returned to our home countries can attest to, the lifestyle in Japan that we enjoyed was ridiculously enticing. Our status as foreigners, gaijin, is often enough of a label to put us in social positions that we would not otherwise enjoy in our home countries where being the cultural/ethnic/religious ‘other’ is more of an accepted part of society. (When I was teaching in Sendai, I could command $75 or more an hour for teaching at a college or privately and this was all under the table. Even living an extravagant life style, I was able to save.)

Ah, oh, and how the time does fly…. Then, one day, you wake up and realize somehow that a door is beginning to close. It is palpable. For most it is a benchmark like approaching middle age when we have to weigh the tradeoffs of living in Japan versus the pragmatic reality of going home and facing up to the harsh realities of trying to fit in again socially and career wise. I’ve been back for almost 10 years and still wrestle with this from time to time.

Similarly, I have met many Japanese who have immigrated and adopted Canada as their new home. Most have done it for reasons of marriage and convenience while others made the choice after finding themselves disenchanted with life in Japan, often feeling constricted by the culture of expectations there for Nihonjin, which are different than for gaijin.

Remembering that most of our grandparents and great grandparents left a still rural Japan 100 years ago because of their limited prospects there, too, it is interesting to observe this pattern repeat itself in both similar and vastly different ways in 2014.

The new immigrant from Japan, the Shin Ijusha, is not much different from the first immigrants from Japan. They have a deeply ingrained Japanese sense of responsibility to be good, respectful, humble citizens of wherever they settle. Like the Issei, this is rooted in culture, religion, tradition and education. Those of us who are third, fourth and fifth generation Canadian simply don’t understand the Shin Ijusha because we were not brought up in that way.

Sure, some might have learned bits and pieces of Japanese culture and traditions from older relatives but it is really not much. What has clearly developed now is, in fact, a cultural and language gap that the Issei anticipated. The Issei established Japanese language schools as a way to ensure that these gaps never developed in the first place. Their closure in the mass hysteria of World War Two meant that subsequent generations were then scarred by the stigma of being of Japanese descent. It is this gap too that the Shin Ijusha wives with children invariably try to bridge by also teaching their children how to speak Japanese.

Learning about Japan did not become ‘cool’ until the 1990s with the boom of manga, anime and sushi. Younger generations subsequently became better informed about their cultural heritage and curious to know about who they are as Nikkei.

Shin Ijusha, Fumi Torigai, 68, a retired music teacher who lives in Whitehorse, Yukon, is one of the few leaders who understands the cultural and historical complexities that have influenced how we have evolved into the community that we have become today.

I had the good fortune to meet Fumi-san a couple of years ago at a National Association of Japanese Canadians conference in Kelowna, BC. Thoroughly comfortable in English and Japanese, he tells me his own remarkable story as well as that of his active group of Nikkei in Whitehorse`s dynamic multicultural community.

* * *

First of all, Fumi-san, can you please tell us a little about where you come from in Japan and your path to getting here?

I was born deep in the mountains of Fukushima, Japan, in the middle of winter in 1945, only six months before the end of the Second World War. My family moved to Tokyo when I was two or three years old, so I have no recollection of my birth place.

I was raised and educated in Tokyo. I quit the university after three years of study. No, I wasn’t expelled! I left on my own accord against the advice of my parents and the academic adviser of my university. Then I worked for a few years in Tokyo before I jumped on the opportunity to work in Canada. This opportunity simply came to me; I did not seek it. The invitation to work on a farm in Ontario was actually offered first to my co-worker on the University Farm were I was working at that time. When my co-worker declined the offer, I grabbed it without any hesitation.

What was the reaction of your family in Japan?

My parents didn’t object to my decision, maybe because I am the second son, and also they thought I wouldn’t be leaving Japan for good.

When did you come here?

When I came to Canada in 1969, I already had a landed immigrant status. The immigration rules were much simpler then. My plan at that time was to stay in Canada only for a few years and to return to Japan. Things turned out quite differently from my original plan. Here we are, 45 years later, my wife and I are enjoying our life in the Yukon as Canadian citizens.

You went to university to study music, didn’t you? How did you become a teacher?

After I came to Canada, I worked for five years in and around Brampton, Ontario; on a dairy farm milking cows; in a greenhouse cutting roses for a minimum wage; for a small firm driving a truck delivering eggs all around Toronto; and then in a small factory manufacturing plastic signs.

During that time, I founded and conducted a community choir in Brampton, called Peel Choral Society, for almost four years. This made me realize that I needed a formal study and a paper to come with it in order to do what I really enjoy doing for a living, rather than a boring job I had to do to make ends meet. So I decided to go back to university. From 1974 to 1978, I studied music at the University of Western Ontario (London, Ontario) and obtained bachelor degrees in music and education.

How long did you teach?

I taught music at the several public schools, from primary through high school level, for 29 years before retirement. The last six years of my teaching career were spent at the elementary school in Whitehorse, Yukon, which was the best part of my teaching career.

In a way, then, you were really an evolving Nikkei from the beginning. How ‘Japanese’ do you consider yourself now? Canadian? Are there elements of both that you can describe?

The number of years I lived in Canada is now almost twice as much as that of my years in Japan. So, am I two-thirds Canadian and one-third Japanese? Well, it’s not that simple. I’m definitely part Japanese and part Canadian. It’s very difficult, however, to define the proportion of them, that is, how much of which. It also depends on your definition of Japanese-ness and Canadian-ness. To explore that topic alone would take pages and pages of discussion. Suffice it to say that I am absolutely proud of being both Japanese and Canadian; or should I say that I am a proud Japanese Canadian.

Can you tell us a little bit about your family? Your wife is from Japan, isn’t she? Where did you meet?

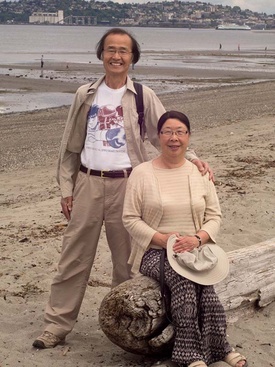

I met my wife, Taeko, at high school in Tokyo. Is she my high school sweetheart, you ask? Well, that sounds sweet and romantic; sounds good enough. Let’s leave it at that. Both of us are deeply involved with the Japanese Canadian Association of Yukon (JCAY).

And your children?

We have two adult children. Our daughter lives and works in Whitehorse. She usually visits us for Sunday dinner. Our son lives in Seattle, Washington.

Both of them love travelling to Japan. In the past the whole family travelled Japan together twice, two children travelled together twice, and they travelled alone or with friends a few times.

They speak Japanese quite well to have a good conversation with their relatives in Japan, except for some topics that require a higher level vocabulary; then they need help. Since they grew up in a small Saskatchewan town, they didn’t have any friends to converse in Japanese during their childhood years. Their understanding of Japanese is quite good, though, because my wife and I speak nothing but Japanese at home.

What is their connection to Japan now?

Our children were both born in Canada, so they are Canadians, well, Nisei Japanese Canadians. Their awareness of their Japanese root, however, is quite significant. They certainly take it very seriously. They are proud of their Japanese heritage, I’m sure.

You have a Japanese Canadian group way up there in Whitehorse. Can you tell us a little about the group and how it came to be?

The Japanese Canadian Association of Yukon (JCAY) was founded in March, 2009 with only 16 members in attendance at our first AGM. It has since grown to be a well-established organization of around 70 members, with some ups and downs from year to year.

Is the membership mostly Shin-Ijusha?

Close to 50% of the current members are Shin-Ijusha; some have lived in the Yukon for 10 years or more and some came to Canada within a year or two. It seems that more and more young Japanese men and women keep moving in to the Yukon. How many of them would settle in the Territory for good, or even in Canada? That’s anybody’s guess.

What are some of your main challenges as a group?

Some newcomers are keen on JCAY’s activities and very willing to participate, but some are not so enthusiastic. In fact the same goes true with long-time members. A lot of times it is not easy to figure out what kind of activities we must plan to keep the members interested.

I think it all boils down to this perpetual question amongst Nikkei: How to bring the Shin-Ijusha group and the Canadian-born Japanese Canadians together? Personally, being a naturalized Canadian who grew up and was educated in Japan and have lived in Canada for 45 years, I sit right in the middle of those two groups. I feel I have a very unique role to bridge these two groups together. And that’s exactly what I try to do as president of JCAY.

© 2014 Norm Ibuki