開国前から始まった日本との結びつき

さかのぼること179年前の江戸後期、尾張(現・愛知県)の漁師3人がワシントン州のオリンピック半島に漂着した。その約40年後、年号が明治に変わり、1869年に旧会津藩の武士らがサンフランシスコに渡ったのを皮切りに日本人の米国本土への移住が始まる。

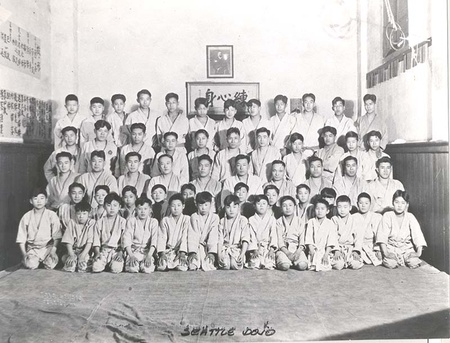

1880年の米国国勢調査では、ワシントン州に日本人1人がいたことが記録されているが、シアトル、タコマ両市への移民は1890年代から増え続け、95年にはタコマ領事館1が誕生。広島、山口、熊本、鹿児島など各県から海を渡った移民たちは製材所や鉄道、農場などで過酷な労働に汗を流した。やがて宗教施設や日本語学校が建てられ、ホテルやレストラン、商店、クリーニング店など日本人経営の店が軒を並べる日本町が形成される。なかには実業家として成功する者も現れ、日本語新聞の発行、文学や芸術、武道など、現代までも引き継がれる数々の「日系文化」が花開いた。

だが一方で、日本人移民への差別の風潮は当初から存在した。州中南部のワパトでは1907年、日本人立ち退き運動が起こる。第1次世界大戦中は労働者不足のため、日本人労働者が重宝がられて日本町も活気づいたが、戦後に経済が停滞すると、排日の気運は再び高まりを見せる。21年には日本人の土地所有を禁止し、リースにも制限を加えるワシントン州外国人土地法が制定され、3年後には帰化不能外国人の入国を禁じる排日移民法が成立した。

こうした動きに反応したのが、米国市民として生まれた二世たちだ。シアトル生まれの坂本ジェームズ好徳は、排日土地法制定に対し正当な権利を主張しようと組織されたシアトル革新市民連盟(21年発足)を発展させ、30年に日系市民協会(JACL)を結成。第1回の会合にはワシントン州をはじめオレゴン、カリフォルニアといった西海岸の州に加え、ハワイやニューヨークからも出席者が集まり、アメリカニズム(米国人化)を呼びかけた。

開戦と立ち退き、それぞれの苦悩

だが時代はさらにうねる。日本はしだいに国際関係で孤立していき、JACL誕生の翌年31年には満州事変が勃発、37年には日中戦争に突入した。日米関係も悪化の一途をたどり、41年12月8日(ハワイ時間7日)、日本海軍の真珠湾奇襲攻撃によってついに太平洋戦争が始まった。日米開戦は日系人にとって長い苦悩の始まりを意味し、真珠湾攻撃が伝えられた同日夜には、日本人会会長や日本語学校校長、新聞社社長などコミュニティーの代表者が連邦捜査局(FBI)に次々に逮捕された。一方、JACLは米国に忠誠を示す声明書を出すものの、米国民である二世に対しても政府の対応は結果的に厳しいものとなった。

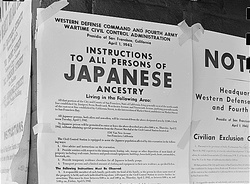

ルーズベルト大統領は42年2月19日、特定の軍事地区を指定して居住者を強制的に立ち退かせることを許可した9066特別行政指令に署名。軍事地区にはワシントン、オレゴン、カリフォルニアの3州の西半分のほか、南部アリゾナが含まれた。この指令によってミネドカ(アイダホ州)、ツールレイク、マンザナー(カリフォルニア州)、ハートマウンテン(ワイオミング州)など全米各地に設けられた日系人収容所には、「敵性外国人」とされた約12万人が送られたといわれる。シアトル周辺に住む約7,000人はミネドカに収容され、近郊のベルビュー、ケントの日系人はツールレイクに移動させられた。

移り住んだ土地に根付こうと努力してきた一世と米国生まれの二世にとって、強制退去は不条理そのものであった。さらに追い討ちをかけたのが、日米の国籍や年齢、性別を問わず突きつけられた質問状、いわゆる「ロイヤリティー・クエスチョン(忠誠登録)」だ。そのうち27項は兵役に対する意思、28項は合衆国に対する忠誠を問うもので、いずれも「ノー」と答えた人は「ノーノーボーイ」と呼ばれ、ツールレイク収容所に集められた。一方、兵役を志願した二世たちは、日系兵士で構成される第442連隊や陸軍情報部(MIS)に配属される。ヨーロッパ戦線に赴いた第442連隊では延べの約1万4,000人が戦い、MISに配属された兵士は太平洋戦線で通訳や捕虜への尋問など後方支援に携わった。彼ら二世兵士の果敢な功績は現代まで語り継がれ、2011年11月には米連邦議会が最高位の勲章となる「議会名誉黄金勲章」を授与している。

■ 権利回復と新たな世代、海を渡る日本人

戦争の形勢が定まると、米国政府の日系人への対応も変化を見せる。陸軍は44年12月、翌年1月から西部沿岸立退令を解除する方針を発表。収容所もすべてが45年末で閉鎖されることになり、住み慣れた町に戻っていく人が出始めた。終戦後、シアトルにいた日系人の多くは帰省したといわれるが、日本町のあったあった現代のインターナショナル・ディストリクト周辺は中国人などが住むようになっていた。しかし、新聞、ホテル、県人会などが次々と再始動、日本との関係も徐々に回復していく。1950年には日本政府の在外事務所が置かれ、2年後には横浜・シアトル間の日本郵船の定期航路が約10年ぶりに再開された。

またこの頃、日本に駐留していた米軍兵士と結婚した日本人女性が大挙して渡米。ワシントン州にも多くの女性が移住し、婦人会を結成して地域コミュニティーや日系人たちとの交流を図った。60年代以降は日本企業関係者も多数シアトル周辺に駐在するようになり、春秋会(現シアトル日本商工会は1971年、駐在員子女たちが日本語で学習できる教育の場を目指してシアトル日本語補習学校を設立した。

日系人に対する補償の動きも始まり、48年には立ち退きに対する日系人補償法の実施、66年にはワシントン州外国人土地法が撤廃された。そして、第2次世界大戦の終結から40年以上が過ぎた88年8月、レーガン大統領は生存する収容体験者に一人あたり2万ドルの補償金を支払うことが明記された「市民自由の法」に署名。強制退去の不公正を正式に謝罪した。折りしもシアトルでは、強制収容に対する賠償請求を長年働きかけ、法案成立を心待ちにしていたJACLの全米大会が催されており、代表団は式典出席のために急遽ワシントンDCに向かったという。

2010年の国勢調査によると(2012年3月発表)、人種を「日系(Japanese)」と回答したワシントン州内の人数は全体の5.2%にあたる6万7,597人で全米3位。世代は四世、五世とつながり、また戦後日本から移住した「新一世」と呼ばれる人々の子や孫も米国人として生まれ、育っている。

注釈:

1.1901年、人口の増えたシアトルに移転し、シアトル帝国領事館となる。

*本稿は、シアトルの日英バイリンガル新聞『北米報知 (The Nothr American Post) 』との共同プロジェクトです。

© 2013 Yaeko Inaba