Read Part 2 >>

LESSONS FROM THE JAPANESE CANADIAN EXPERIENCE

Amateur volunteers working on a shoestring, we Japanese Canadian activists were armed with resolve and blessed with lucky timing. Post redress, other communities and struggles have examined the Japanese Canadian Redress victory to learn from our mistakes and successes. Of course, our experience is not necessarily transferable to other issues or locales.1

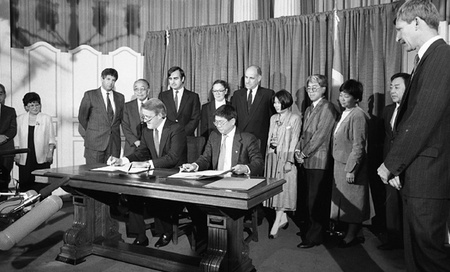

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Art Miki sitting down at the signing of the redress at Parliament Hill, Ottawa, ON in 1988. A row of people are standing behind them, Roger Obata, Gerry Weiner, and Cassandra Kobayashi are amongst them. Judge Omatsu is in the middle of the row behind the Prime Minister (Gordon King collection, Nikkei National Museum. [#2010.32.57])

1. Determination

Famed 16th century Japanese samurai Miyamoto Musashi wrote, “Combat makes apparent something that already exists. A battle is always won before it begins, since it is won in the mind.”2 Having decided to challenge the past, we immediately found ourselves thrown into a psychological boxing ring with masters of manipulation. However, we were prepared to hang in for the long term, oftentimes by our fingernails. Certainly when we started our campaign for justice, no oddsmaker would have placed money on this ragtag group of determined amateurs. Still, even in the bleakest times, the NAJC refused to give up. We felt the onerous obligation to regain not only our own personal family’s honour but also that of our community. After continual rebuffs by government, we would gloomily predict that this fight was the unfortunate legacy that our children would inherit.

2. The Long Haul: Political Struggle and Gramsci’s War of Position3

Antonio Gramsci wrote that every political struggle has a military substratum. In the war of position, the winner exercises patience and chooses his battles, avoiding confrontation when exposed. Guerrilla warfare follows this stratagem.

We knew that our community could never survive a head-to-head confrontation with the government. David with his slingshot needed only hit Goliath’s tragic flaw with devastating speed and accuracy, but we lacked even David’s simple weapon. It seemed that our best plan instead was to pursue the strategy outlined by Musashi, who advised when fighting a stronger opponent to attack the enemy’s strategic corners, thereby weakening him.

On the last day before the House of Commons rose for the September 4, 1984, federal election, Brian Mulroney, leader of the opposition, in a heated exchange with then prime minister Pierre Trudeau, publicly pledged to “compensate” Japanese Canadians if he were elected Prime Minister. The Liberals were turfed out of office with the largest landslide in Canadian history and Mulroney was elected to the highest political office in the country. We did not let Mulroney forget his promise to us.

3. Community Organizing or a general needs to know that his foot soldiers are behind him

Organizing a community of some 50,000 individuals, who spoke two languages, spanned a three generation cultural divide between the Meiji and 20th century and were spread thinly across the second largest country in the world, was a crash course in grass roots organizing. To bridge the various chasms and avoid the minefields required sensitivity, community education, and much discussion. Concretely it meant meetings, gallons of coffee, late nights, handbills, posters, and more meetings, coffee, no sleep, lobbying, writing, and strategizing.

Nowhere in Canada was the battle for community hegemony more acrimonious than in the Toronto area, which had the largest number of Japanese Canadians (14,000) and internment camp survivors. The split was between those who were prepared to accept the government’s offer of an apology and a $5 million fund and those who wanted to fight for individual compensation and civil rights guarantees. Most of the Toronto Japanese Canadians were ignorant of redress developments, fearful of a racist backlash, and desirous of consensus.

The Issei (first generation) coming from a culture of shame4 believed that if a party admits guilt, the other party must forgive them. Traditionalists argued that the community was obliged to accept the government’s apology and drop the matter. Culturally, Japanese act upon consensus. Even in Canada, the NAJC could only proceed once a broad consensus had been reached.

In 1982, aware of the deep schism within the community, a group of primarily Sansei (third generation) lawyers formed the “sodan-kai” (group to reach consensus). “Sodan-kai” organized a series of house meetings and open forums. The public gatherings were packed as most of the former Nisei (second generation) activists from the 1940s and the community’s public figures came to listen to the arguments of the two factions. Ultimately agreement was reached and the community backed the decision to undertake the difficult and long battle with the government.

4. Choose your weapons

Japanese Canadians unlike Japanese Americans did not use the courts or formal political avenues in their fight for redress and instead worked on mobilizing and educating the community and the public.

i) Powerless Community

The path that we followed was chosen not from strength but from weakness. Japanese Canadians lack representation in the Canadian power elite. As compared to the United States, we had no senators, politicians, or senior judges5 to influence the state’s apparatus. Out of necessity, ours was a grass roots’ movement required to make Japanese Canadian redress a concern of all Canadians.South of the 49th parallel, reparation for Americans of Japanese ancestry had become a political question, fought out in Congress and not on the editorial pages of the country’s newspapers as it was in Canada. In the U.S., the bulk of the Japanese Americans community’s efforts was directed to getting the 1982 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians recommendations as embodied in the “Civil Liberties Act” through Congress and signed by President Ronald Reagan.6 In Canada, we lacked the power to meet with then Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, let alone lobby him to pass a non-existent Japanese Canadian Redress bill.

ii) Bad Laws and Bad Legal Precedents

We were confounded by a long history of self-serving laws and racist legal decisions from the highest level that continued to protect the Canadian government from challenge in the courts. Under the umbrella of the “War Measures Act”, all actions taken against Japanese Canadians were strictly “legal”. In addition, Japanese Canadians had no rights of citizenship until 1949, no constitutional protections until 1985,7 upon which legal actions could be framed, no legal animal called “expungement” as exists in the U.S. and we faced an impenetrable “Statute of Limitations”.iii) Non-litigious Nature

Habitually Japanese (in Japan) do not use the courts to settle disputes.8 It is conventional wisdom in Canada that American political culture places a higher priority on the legal rights of individuals and is suspicious of government; while Canada is imbued with a Tory-like ethic of “peace, order, and good government.” Put those two together and add the fact that we were running on empty and it is understandable that suing the Government was not the first line of attack that came to the community’s mind.Nevertheless the Japanese Canadian redress movement was top-heavy with Sansei lawyers with a common vision: to use the law to bring about justice. During the 1970s and 1980s, my counterparts in the U.S. were busy suing their government and bringing forward constitutional arguments. Enviously we Japanese Canadian lawyers watched their ingenious motions and plotted our own strategies. Over the years we left few stones unturned in our quest. Our considerations included:

i) a repeal of the “War Measures Act”, the law that had permitted the draconian measures taken against the community from 1941-49;

ii) an amendment to the Canadian Constitution (1982) to better safeguard against a re-occurrence of the mass internments or expulsion of a hated minority;

iii) a public inquiry similar to the American Commission into the Wartime Treatment of Japanese Americans;

iv) a United Nations Human Rights complaint criticizing the wartime treatment of Japanese Canadians;

v) a legal declaration that today the locking up of whole communities would be contrary to the Canadian Constitution;

vi) a law suit seeking the courts to find improper the U.K. Privy Council deportation decision of 1947 that permitted the exile and deportation of Canadian born Japanese, thus making no distinction between those persons born in Canada and elsewhere. In the end, our brush with the legal system would ultimately play a minor role in our victory.

On examination, we discovered that all but the last (the deportations issue) were primarily political and not legal, in nature. Thrown into the political forum, the NAJC was able to take advantage of some differences that existed between our two countries, twenty years ago. In contrast with the U.S., Canadian culture places a higher value on the preservation of “multiculturalism” as opposed to the melting pot, and appeals to social justice and equity strike receptive chords in the populace as a whole.

The result was that Japanese Canadians could successfully appeal to these sentiments. Without exception when we took our case directly to the public—by explaining our history in forums like high school auditoriums, community or church basements, trade union halls, and so on—our audiences expressed shock and outrage at our treatment. Thus, even though Canada was beginning to feel the effects of the economic downturn by the mid-to-late 1980s, the government’s argument to eliminate or grant minimal financial compensation was in the end rejected even by them. The decision to grant redress was upheld by public opinion polls and press sentiment, even by conservative newspapers.

5. United Front

Build alliances and link up old fights and heroes with today’s struggle. Good advice and something we would improve on next time around. Although Japanese Canadians are a tiny minority, given our high rate of intermarriage and our 125 years in Canada we are linked to many communities. During the Redress years, we called on former allies. The Churches, the New Democratic Party (formerly the CCF), minorities communities (Jewish and Mennonite), human rights organizations, and the YMCA had argued against our lack of civil rights and our deportations after WWII. Forty years later, new supporters—other minority communities (notably the Chinese and Italian), city councils, the media, and the unions, joined these old friends. Individuals with personal ties to the issue or community such as John Fraser, Speaker of the House of Commons, and Phil Barter, a senior partner at Price Waterhouse, came forward. The list could go on.

6. Scope of Demands

The claim for individual compensation sought by the community addressed the interests of those who had been directly affected by the incarcerations, deportations, property loss, and civil rights denials. The more altruistic demands of the repeal of the War Measures Act to protect human rights and the establishment of a Race Relations Foundation to fight against discrimination spoke to all Canadians. The Race Relations Foundation was to be the “jewel in the crown” of our settlement—the legacy that we left behind to help other minority communities fight against discrimination and for equity.

CONCLUSION

Like many of you here, I too have puzzled long and hard about prejudice and the strange fruit it bears. As our history illustrates, at one time Japanese Canadians were visible, shunned and discriminated against, the most hated minority in the country. The transformation from most hated minority to ethnic “success story” says much about the rate of cultural and genetic assimilation of Japanese Canadians, but also about the change in Canadian tolerance and social attitudes.

Formerly inward-looking, my community has been energized by our redress victory. One of our first acts was to set up a Japanese Canadian Native Task Force to investigate how we could best lend support to the most badly treated people in our country, the Aboriginals. Empowered by our own recent success, we felt the need to share our good fortune with others.

Although the history of Japanese Canadians illustrates the disciminatory attitudes that have dominated the past, today’s accommodation of cultural diversity is a lesson in tolerance and demonstrates a revolutionary change in mindset. This dramatic turnaround in attitudes over the past three decades speaks well of the dominant Anglo Canadian majority.

As Japanese Canadians disappear into the genetic wash of North America, we will leave behind our successful struggle for redress for the WWII injustices as a shield and a precedent for others. In your country and mine, historically discriminated groups (Chinese and Black Canadians and American Blacks) look to the redress settlements as a precedent to assist them in their claims.

We have all lived through the fury, paranoia, and sorrow following September llth. An angry chorus recalling the bombing of Pearl Harbour demanded the mass internment and or expulsion of Arab and Muslim communities from North America. Unlike in 1941, both American and Canadian heads of state showed political leadership and quickly acted to douse the racist flames. Today individuals are being questioned and detained, as were German and Italian Americans and Canadians during World War II; however, there is no state action to incarcerate, deport, or confiscate the property of entire communities.

It is often said that those who do not know their history are bound to re-live it. It is my belief that the redress settlements in both our countries will prevent the toxic cocktail of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and the failure of political leadership”9 that poisoned our continent in the 1940s, leaving behind a maelstrom of human suffering and shame.

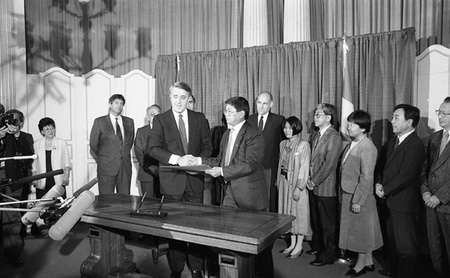

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Art Miki are shaking hands after the signing of the redress at Parliament Hill, Ottawa, ON in 1988. A row of people are standing behind them, Roger Obata, Gerry Weiner, Cassandra Kobayashi, a Roy Miki are amongst them. (Gordon King collection, Nikkei National Museum [#2010.32.60])

Notes:

1. In Canada, hepatitis C victims and thalidomide children have acknowledged that the Japanese Canadian decision assisted them in receiving individual reparations in class action suits for harm done through government action. As well, Chinese Canadians argue the redress precedent in their ongoing claim for compensation for being the only immigrants required to pay a head tax to enter Canada. As well, Aboriginal WWII veterans are demanding payment because they have received less benefits from white soldiers. In the U.S., the Japanese American settlement has drawn interest from those involved in the African American lawsuit against corporations that have benefited from slavery.

2. Miyamoto Musashi, The Book of Five Rings, 1643 (New York: Bantam, 1982) p. 72.

3. Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebook (New York: International Publishers, 1971) pp. 229 – 239. Written in prison between 1929 – 1934.

4. Ruth Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture, (Rutland, Vermont: Charles Tuttle, 1946) and Braithwaite, John, Crime, Shame and Reintegration, (Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 100.

5. By 2013, there are a handful of Japanese Canadian elected politicians.

6. Shirley Castelnuovo, “Compensatory Justice: The Case of Japanese Americans Imprisoned During World War II,” presented at the American Society for Legal History, October 1993, Memphis, Tennessee.

7. Canada introduced a constitution in 1985 but equality protections came into effect in 1985.

8. Japanese reluctance to go to court is referred to as 20% justice. Ten % of disputes are settled through a trial and 10% through consultation with a lawyer. The reasons, in addition to cultural aversion to airing one’s dirty linen in public, are a slow, expensive, and cumbersome justice system.

9. Chair Joan Bernstein, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Part II, (Washington, D.C., 1983) p. 5.

The paper “Lessons from the JC Experience” was given on May 21, 2002 at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. The Honourable Madam Justice Maryka Omatsu was the William Timbers lecturer, a guest of the Nelson Rockefeller Center & the Dartmouth Lawyers Association.

* * *

* Maryka Omatsu will be speaking at “Border Crossings: A Comparative Assessment of Japanese American and Japanese Canadian Redress” session at JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity on July 4-7, 2013 in Seattle, Washington. For more information about the conference, including how to register, visit janm.org/conference2013.

© 2002 Maryka Omatsu