A retired photographer, I volunteer at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), in Little Tokyo, downtown Los Angeles.

Having been and still involved in photography is why I was so impressed when I learned about Jack Yoshihide Muro. He was a photographer too. Jack was also like me, an inmate of Amache, a concentration camp, one of ten such War Relocation Authority camps scattered throughout the United States holding up to 120,000 of America’s Japanese as civilian prisoners for the duration of World War II. You will learn why I was so impressed and why I took the liberty, with his approval, of dubbing Jack Muro, “The Underground Photographer of Amache.”

I was introduced to Jack Muro by Dr. Bonnie Clark, an associate professor at the University of Denver Department of Anthropology. She had met Jack in 2007 at research meetings she was holding at JANM with other former Amache inmates when she was organizing her 2008 Amache archaeological research project. After meeting Dr. Clark, I volunteered as a photographer and field worker on her 2008 Summer crew. My 16-year-old grandson, Dante Hilton-Ono joined the archaeological dig as well. http://portfolio.du.edu/amache

In 2012, Dr. Clark visited Los Angeles and presented a “Dig Amache” lecture at JANM about her 2008 and 2010 archaeological survey findings. Following her wonderfully enlightening presentation, she took me to meet Jack Muro and his wife, Kate Kei (Tanji). From that meeting, Jack Muro’s amazing story unfolds…

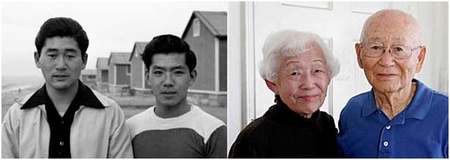

Left photo: Jack Muro (L) and friend, George Matsushita, Amache - ca 1943; Right photo: Kate (Tanji) and Jack Muro, 2012

In 1943 at Amache, at the age of 22, Jack learned photography from professional photographer, Tosh Matsumoto, a relative by marriage.

What was so amazing about Jack Muro was that after he’d begun to learn photography, he built his own photographic darkroom in the corner of his Amache barrack, underground beneath his bunk! He dug out a 3' x 6' x 7' darkroom with a boarded ceiling and a trap door access! This was only possible because in the Amache internee barracks, unlike in the nine other WRA camps which had solid concrete or wooden plank floors, Amache had dirt floors tiled over with bricks without mortaring.

So, Jack simply removed enough bricks the width and breadth to expose and excavate the dirt for his seven-foot deep darkroom. He scattered the excavated dirt about the Amache compound, but unlike the prisoners of German POW camps portrayed in the movies, Stalag-17 and The Great Escape, he didn’t have to secretly spread the dirt like they did from their pant leg pouches to hide the fact that they were digging escape tunnels to freedom.

Jack brought his camera, films, photo-papers, and chemicals from a photo supply house in Des Moines, Iowa through an Amache Co-Op Canteen catalog. He built his own photographic enlarger, using coffee cans to house a light bulb and used the lens from his Argus C3 camera as the enlarger lens. His electrical power for his red safelight and enlarger came from the single bulb light socket that hung in each barrack section. He would prepare the photo-chemicals, pour them into trays, and have a bucket of water handy to hold his processed films and photographs.

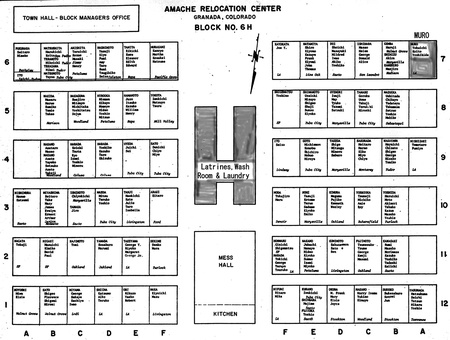

Jack would carry the bucket with processed films or prints to wash in the Latrine, Wash room, and Laundry facility located centrally among the (12) barracks which comprised his 6H Block. No easy task, for Jack had to walk some distance carrying the filled-bucket to and from the water source facility. This was usually in the evenings, best time for photographic darkroom work.

In the diagram below, the shaded area in the upper right-hand corner shows where Jack lived with his father, Tokuichi, and his mother, Koito, in section A of their barrack 7. The H-shaped building (shaded, center) housed the Latrine, Wash rooms, and Laundry facility.

Click to enlarge. Block diagram, one of (29) Block diagrams, produced by the Amache Historical Society for a 1994 Amache Reunion in Las Vegas. The AHS members got the internee family names and their locations from the 1944 Amache Directory

After the prints and/or films were washed, he would bring them back to his underground darkroom and hang them to dry on string lines suspended below his darkroom ceiling. Jack said his darkroom was relatively free of the ever present dust that blew constantly around Amache and even into their barracks.

Jack Muro took family and friends photographs like other internee snap-shooters, but he ventured out all around Amache with his camera. He held a variety of jobs for “not wanting to be tied-down,” so he was able to graphically capture a wide range of Amache activities and events. Jack photographed work places, people, dogs, and camp events. He also climbed the water tower and photographed a panorama of Amache. He captured crystal cold winter scenes as well. He made beginner mistakes, such as: double exposures, over or under exposure, light leak issues, film scratches, etc., but overall his photographs were well composed and spoke “a thousand words.”

At the age of 92, Jack Muro donated his long-held and little known collection of photographic prints and negatives to JANM. His collection will be my volunteer job and pleasure to scan into digital files for future archival access. His coverage of a wide-range of subject matter will help to provide rich imagery to help illustrate a more complete story of the busy life in Amache, of a group of people making the best of a terrible situation. A striking historic pictorial essay was produced by Jack Muro, “The Underground photographer of Amache.”

* * *

Author’s Notes: To see examples of Jack Muro’s photographs, please check the Jack Muro Amache Photo Album in the Nikkei Album section of the Discover Nikkei website. You will be pleasantly surprised to see his insider’s views of Amache. For other related essays of Amache and about the Jack Muro family, read the other Journal articles by this author.

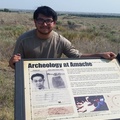

Jack Muro near the 6H Block of barracks. From "Jack Muro Amache Photo Album" by Gary Ono. Gift of Jack Muro, Japanese American National Museum (2012.2.309)

© 2013 Gary T. Ono