Before the advent of the offset printing process, The Rafu Shimpo handset every word, every comma, every dingbat and ornamental header, utilizing drawers of lead type. In the case of the Rafu, the metal kanji used to compose each page must have been imported from Japan and cost a fortune, weight several tons in total. In 1926, it was the oldest and largest Japanese newspaper serving the immigrant population of the greater Los Angeles area.

That same year, the Rafu made a bold decision to deliver a full set of Roman fonts, heralding a massive transition for the paper. To oversee the paper’s introduction of a selection of English language pages, publisher Henry Toyosaku (H.T.) Komai hired its first editor-in-chief. She was a 20-year-old student at UCLA and her name was Louise Suski.

Louise J. Suski was born in San Francisco on June 27, 1905, the second daughter of a prominent and trusted community doctor. As a teenager, Suski explored two common outlets for Nisei girls: church (her father was baptized in Japan and the family attended Maryknoll Catholic Church) and Nisei youth clubs (she and her siblings belonged to the first girl’s Olivers Club in 1919 and later were active with the YWCA). After graduating from Los Angeles High School in 1924, she applied to UCLA with the hopes of becoming a kindergarten teacher and majored in education.

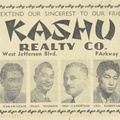

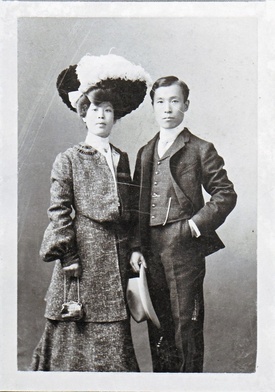

Her father, Dr. Sakae Suski (also known as Peter M. Suski), was born in Okayama Prefecture in 1875 and immigrated to the United States in 1898. He made a living as a photographer in San Francisco until 1906, relocating to Los Angeles following the Great Earthquake. Upon establishing himself in Los Angeles, he opened his own studio specializing in retouching, which required a steady hand painting over prints. By 1908, his dedication to the Los Angeles immigrant community was renowned, and he served as managing editor of the Southern California Association for the Preservation of Japanese History. As his family grew, he realized that photography was insufficient to support them, so he enrolled at the USC medical school while working at night. In 1917, he even spent a year in specialized study at the University of Berlin while the family remained in Los Angeles.

Dr. Suski was also a writer, linguist, and a close confidant as well as the personal physician of H.T. Komai. Komai understood that if he wanted his Nisei children to read the Rafu, he absolutely had to dedicate pages to the emerging population of English readers. Together, Dr. Suski and Komai hatched a plan for the future and survival of the paper, and Louise was recommended for the position of editor in chief. When her father asked her to help out in starting the Rafu’s English section, she quickly responded to his request. “I thought I would give it a try, although English was not my favorite subject,” she said. Despite her lack of newspaper experience, Komai entrusted Louise with the project and on February 21, 1926, the first quarter page of English laid into The Rafu Shimpo hit the streets.

The three founders of the Rafu had published an English supplement as early as 1904. Between 1910 and 1926, several efforts also were made to publish English articles in the paper, the first appearing as a supplement to the New Year Issue on January 1, 1917 as a supplement. For this special English publication, The Rafu Shimpo temporarily adopted the name the “Los Angeles Japanese Daily News.” The one and a quarter pages of the supplement consisted of letters from prominent officials, dignitaries, and journalists in Los Angeles such as the mayor, the president of the Los Angeles chamber of commerce, the Los Angeles postmaster, the Los Angeles police chief, the pastor of Temple Baptist church, and the president of USC, which indicates an outward attempt by the newspaper to bridge between the Issei and the white American communities that lay mere blocks apart.

From May to September 1918, English columns were written by Giko G. Sakamoto, and in 1921 and 1922, the Rafu held an English essay contest for Nisei and printed the winning results in their Christmas issues. Additionally, from 1924-1926, the paper ran a serial English comic.

Although the paper was written in Japanese, it also served as an English advertising medium for non-Japanese speaking Americans and circulated among them. Unlike Jewish and Italian immigrant newspapers, the English section of the Rafu was created as a cultural bridge to ease international tension. After the passage of the Alien Land Law of 1913, the Foreign Ministry of Japan and Japanese community leaders in the United States tried to educate Americans about Japan and its people because they thought that the anti-Japanese movement was rooted in Americans’ ignorance of Japan and the Japanese.

It is no accident that the first established English section was initiated two years after the passage of the 1924 National Immigration Act. Since more Japanese immigrants were not expected to enter the US after 1924, various businesses in the Los Angeles Japanese community were forced to change, aiming at English-speaking customers and other immigrants for survival.

Most Nisei at that time were minors, so they weren’t regarded as advertisers or paid subscribers. The Nisei were also isolated from the mainstream because of their color, and the truth was that they needed a media that would lead the fight against racism, as African Americans also needed their own papers.

“Our long-hoped for wishes are materialized, and so here we have a medium to publish news of the second generation, for the second generation, and by the second generation.”

—announcement, Rafu Shimpo, 21 February 1926.

The daily process of creating The Rafu Shimpo newspaper was a tremendous effort that nearly consumed a full twenty-four hours. Every step had a deadline, although Suski herself called it a “hit and miss situation,” and there were no set policies. The role of editor might encompass recruiting writers, making the final call about stories to run, copyediting and proofreading, and working with the composer on the page dummies to fit the headlines, stories, and advertising. In later years, when the paper was no longer letterpress printed, work included assigning columns to be typed, laid out, and pasted.

In April 1932, the paper installed a four-deck rotary Goss press, replacing the old flat-bed press. The installment of the new machine enabled the paper to publish a tabloid, print clearly, and produce 25,000 copies an hour. Newspaper veteran Harry Honda remembered Louise Suski as “the Queen Bee at the Rafu prewar, with us young cub reporters writing stories and helping out the English section.”

What started as a cultural bridge to help ease international tensions quickly became a voice for the Nisei, reflecting their sentiments, their gossip, and their moral watchdog.

By 1932, the English section was a daily feature, informing young folks about what was going on in the city and elsewhere, but also containing articles about Japan in order to teach Nisei about the country that their parents called home. Dr. Suski himself became a regular contributor to the English section, writing essays on the Japanese language for the benefit of Nisei readers. He also collected books on linguistics and the ancient forms of Chinese characters.

Of various kinds of newspaper work, Louise later admitted that she loved reporting female sports—her childhood dream had been to be a physical education teacher, but her mother had discouraged her and led her to instead study general education (although the job at the Rafu developed into a full-time job and she never finished her degree). Louise covered the women’s sports and reporter Tony Gomez covered the men’s sports.

In June 1933, Suski was joined by George Nakamoto, a Fresno native who had studied journalism at the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University as a co-editor. Three years later, the Rafu hired Togo Tanaka as another editor on staff.

In the wake of the Pearl Harbor bombing, publisher H.T. Komai was arrested and detained for his role with the press. With the imminent removal of all Japanese Americans off the West Coast, The Rafu Shimpo ceased publication on April 4, 1942.

The Suski family was sent to Heart Mountain camp, where Louise immediately joined the camp newspaper, the Heart Mountain Sentinel, with Bill Hosokawa as its editor. Among the dozen or so who worked in the Sentinel office, there were a few professional journalists such as the paper’s managing editor, Haruo Imura, who had worked in San Francisco, and of course, Louise. But most of the staff had little or no reporting experience.

An article written by Kelly Yamanouchi reports: “Throughout the week the typewriters clacked away in the makeshift office; on Friday afternoons, the staff would gather to paste up the copy and then send it off for printing. The presses would churn out 7,000 copies of each issue, which would then be distributed free of charge to the camp’s occupants.”

Once Heart Mountain closed, the Sentinel, which had grown from a pamphlet newsletter into an eight-page tabloid, released its final paper on July 28, 1945 after 145 issues.

Following the war, Louise moved to Chicago and continued to write for Japanese American publications, reporting on the lives of Nisei in Chicago and Milwaukee who were trying to eke out a new existence in the Midwest. “I was not anxious to come back to Los Angeles because they did not want Japanese on the West Coast. There was a lot of prejudice against Japanese.”

In Chicago, she found work with the General Mailing and Sales Company, which was owned by a Nisei, and at the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Program (JERS) office, collecting data such as evacuee letters, diaries, photos, and reports submitted by social scientists and journalists. She also helped edit Scene Magazine, a Japanese American magazine published by her former co-editor, Togo Tanaka, and the Shikago Shimpo (Chicago Courier), a JA paper published in Chicago by Roichi Fujii. According to Harry Honda, “She often said that she was helping put out one page of English as a public service. She wasn’t getting paid and she liked to just keep her hands in what was happening in the Nisei community.”

In 1978, Suski returned to Los Angeles to spend the rest of her life after her retirement. She returned to live with her brother Joe and his wife in Cerritos. Altogether, there were seven Suski children: Julia, Louisa, Flora, Clara, Margaret, Margaret, Joe, and Elmer, who is still living. The eldest, Julia was a musician and artist, whose pen illustrations appeared almost daily in The Rafu Shimpo from 1926 to 1929.

Louise Suski died in June 2003 in Cerritos, the start of a legacy of newspaper women at the Rafu that led me to my first column, printed just a week shy of the English section’s eighty-sixth anniversary.

I thank Harry Honda, Lon Kurashige, Chris Komai, and Alan Kumamoto for their assistance in researching this article.

* This article was originally published on The Rafu Shimpo website on March 3, 2012.

© 2012 Patricia Wakida / Rafu Shimpo