My father was the resident minister of the Seattle Buddhist Church. The construction of the temple on 14th Avenue & Main Street was nearing completion. It carried a heavy mortgage and payments had to be made. A cornerstone laying ceremony was held on March 16, 1941. These jubilant members had no idea that WWII would start later that year to disrupt their lives.

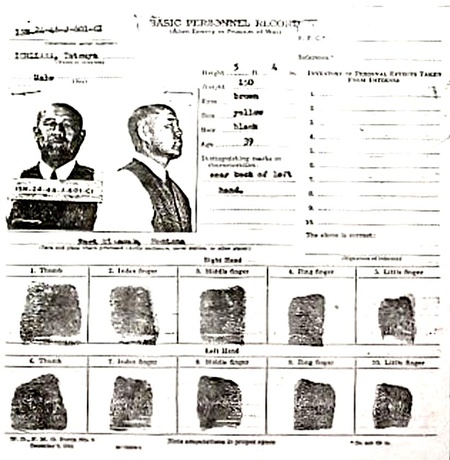

War broke out between Japan and the U.S. with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, HI on December 7, 1941. Dad was arrested by the F.B.I. in the Spring of 1942. The below is his mug shot. With all the church leaders and members evacuated due to Executive Order 9066, the temple was leased to the U.S. Maritime Service and used as its district headquarters to shelter staff and trainees.

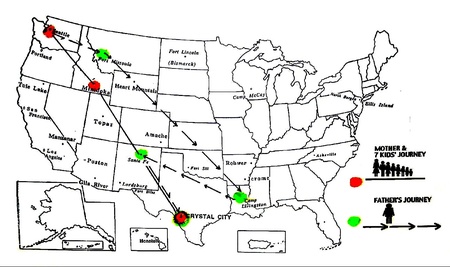

Dad and Family Travel Separate Ways

The family was separated from Dad during the first two years of the war. The map shows our family’s travels. He was sent to Fort Missoula, MT; Camp Livingston, LA; and Santa Fe, NM.

He was considered a “Dangerous Enemy Alien” along with many other Issei community leaders. We, in turn, were taken to the Puyallup Assembly Center and later to Minidoka, ID.

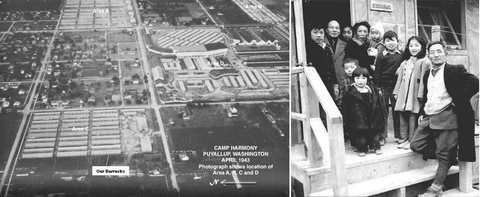

My mother and seven children from the youngest at 4 months to me at 13 years, were bused to Camp Harmony, Puyallup, WA. We brought only what we could carry. We spent three months in Area C by the Fairgrounds—a large parking lot hastily converted into a camp with barbed wire fence and armed guards in watch towers, 24-7.

After 3 months in Puyallup we were moved by train to a WRA prison camp in the dusty, lonely sagebrush country of Minidoka, ID.

The family gathered in front of the Minidoka barracks at Block 13-1-E with two friends, Mr. Y. Suzuki and Mr. R. Hino. My mother carries the youngest son. I’m the boy standing to the left by the door. An official camp photographer snapped this photo. We were not allowed to bring cameras into camp.

(Left) Camp Harmony Puyallup, Washington on April 1943. Photograph shows location of Area A, B, C and D; (Right) My mother with her seven children, ages six months to 12 years old at Minidoka, Idaho, Block 13-1-E. My father was taken away and separated from the family for two years during WWII. Pictured here are family friends, Mr. Yahachi Suzuki in the front and Mr. Hino in the back. (Picture courtesy of Minidoka photographer Jack Yamaguchi)

Voiced through Censored Mail

Since Dad was miles apart from us, letters were the only means of communication. These were all censored. Some 85 letters were from Dad. 19 were saved from Mom’s collection. Obviously, Dad had more time to write than Mom, who was busy taking care of 7 kids.

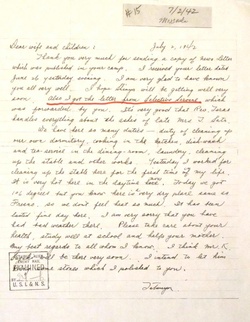

My father’s first letter, written on July 2, 1942. He received one from the Selective Service... (click to enlarge)

The first letter Dad sent was written on July 2,1942 from Ft. Missoula, MT. Note red underline. He received a notice from the Selective Service forwarded to him from Mom. I’m sorry, I don’t have a copy of that one. It may have notified him of his draft status.

Another one is from Ft. Missoula, Montana, dated July 31,1942. Note that the censor cut out 3 words in the letter. There’s a censor’s stamp in the lower left corner with the words “Detained Alien Enemy Mail examined by the U.S. Immigration & Naturalization Service.” Censorship was eased when the tides of war turned to the Allies’ favor.

Click to see the censored “Alien Enemy Mail” on July 31, 1942 >>

Here’s one from Camp Livingston, LA., an Army camp. He had some initial thoughts about repatriating to Japan. He asks for a pair of “geta.” Must be very muddy there.

Click to see the letter from Camp Livingston on August 16, 1942 >>

He writes about repatriation, again, but feels he owes a heavy responsibility to the Seattle temple. He must complete the job he had set out to do. The church carries a large mortgage that must be paid off. He will contact Mr. Ito, president, and other directors of the temple.

Click to see the letter on August 20, 1942 >>

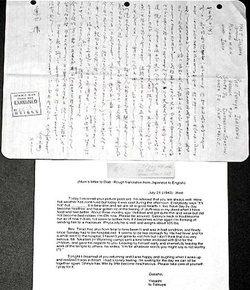

Mom’s letter to Dad written in script Japanese. It’s difficult for me to translate. I did the best I could, so that my siblings could learn what Mom wrote. The censor had to know the Japanese language and what to cut out. I took some liberties in the translation.

Here’s a blowup of that letter. Mom expresses her private feelings and hopes for the family to reunite.

Click to see the translation of my mother’s letter from July 21, 1943 >>

Mom writes about the Obon Service in Block 14. “Whenever there’s a service, I think about you. It’s unexplainable but I feel that you are somehow present.”

Click to see the translation of my mother’s letter from August 17, 1943 >>

Mom expresses her thoughts. “These days I dream about you every night. At least I feel fortunate that I can meet you in my dreams.” Doctors were scarce in camp, and there’s a rumor that an excellent doctor, Dr. Hashiba, would arrive soon.

Click to see the translation of my mother’s letter from November 12, 1943 >>

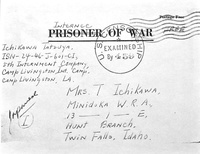

In Camp Livingston, LA, Dad used government issued mailing forms with the words “PRISONER OF WAR” printed on the face. He had to cross out the words “Prisoner of War” and write in “Internee of War”. The government went to great lengths to call us “Voluntary Internees or Detainees” rather than “Prisoners of War.”

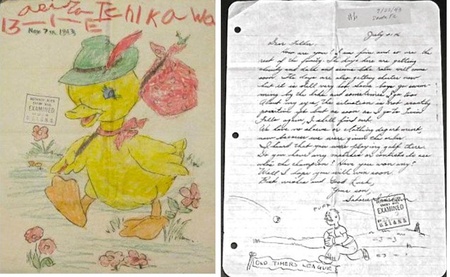

Akira, my younger brother, age 5, colored in the drawing furnished by Rev. H.E. Terao in the camp Sunday School. Note the censor’s stamp on a child’s picture.

I mailed him this one showing the Old Timers’ Softball game. I drew in the Minidoka water tower in the distance. I asked him if he enjoys playing golf. Dad wrote he played golf in the Santa Fe camp with other Issei prisoners. Would that make Mom a “golf widow”?

A Red Cross letter to Dad from Grandfather in Japan, dated August 26, 1943 during the heat of the war. It reads in Japanese, “Kazoku mina kenzai nari ya. Toho buji nari. Anshin se yo.” Roughly translated, “We are all well here...so don’t worry.”

Click to see the “Red Cross letter” from Grandfather Ichikawa in Japan from August 26, 1943 >>

These Issei inmates were all from Nagano-ken Prefecture in Japan. My father is seated in the second row to the extreme right in black jacket and work pants. At front row right, is Hamao Hirabayashi, an uncle of Gordon Hirabayashi, the University of Washington student who challenged the curfew during the early days of the war, and was jailed for breaking it. Gordon was later exonerated in a celebrated case and was awarded the President’s Medal of Freedom.

Dad asked the Santa Fe Camp Authorities for a “temporary parole” to visit the family in Minidoka. The children, especially the youngest two, were seriously sick in the hospital. The request was denied. However, the camp authorities must have realized the extreme hardship separation of family creates. It may have helped us to be reunited in the Crystal City, TX camp.

Request for temporary parole was denied. Click to see the letter >>

Mom writes to Dad that the two youngest kids were sick in the hospital and the nurse told her they were in no shape to travel. We may have to delay the much awaited reunion.

She adds, “Quick-to-act Satoru has already packed all his baggage to go.”

Click to see the translation of my mother’s letter from January 21, 1944 >>

This is the last letter Dad mailed to us from Santa Fe. He writes, “When do you expect to leave there for Crystal City? I expect that we can reunite soon after two years’ separation.”

Click to see the last letter from his Father

before family reunites in Texas on February 15, 1944 >>

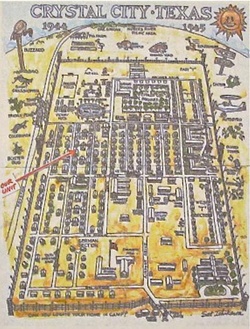

I drew this map of the Crystal City Family Reunion Center. It shows the layout of the camp. The red arrow points to the barracks we occupied. This Dept. of Justice camp was also surrounded by barbed wire fence and guard towers. It imprisoned not only Japanese families, but German families and a few Italians. It had American and Japanese schools. I attended both.

This document dated November 7, 1945 instructed Dad to appear for a hearing. It gave him an opportunity to oppose his deportation to Japan. It provided for a family member (namely me) to testify in his behalf. I told the panel that Dad never was disloyal. He always taught us to respect our country. Many of his former Sunday School kids were now fighting for our country. The result of the hearing shaped our lives. I must have given them a favorable impression, since he was released.

Click to see the “Notice of Determination for Repatriation of Aliens” >>

This important letter instructed us that we were free to return to Seattle. We were “voluntarily interned.”

It tells Dad, “Mr. Ichikawa, you are further advised that it will be necessary that you report to your Draft Board immediately upon arrival in regard to your change of address and occupation.”

Click to see the letter from March 6, 1946 >>

THE AMERICAN PROMISE. This document officially apologizes for the internment of Japanese Americans. Our government made a mistake in doing so. It brings to a close Executive Order 9066 and promises that this type of action will never again be repeated.

Signed by President Gerald R. Ford in the Bicentennial year of our country.

To see the Government Apologies for E.O. 9066 >>

*Satoru Ichikawa was a panelist for the “In My Parents’ Words: Voices from Department of Justice Camps” session during JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity in Seattle, Washington.

© 2013 Satoru Ichikawa