At California State University, Fullerton, I taught history, Asian American studies and American studies courses. My favorite was an American studies offering developed in the mid-1970s: “American Cultural Radicalism.” If now teaching it, I assuredly would assign Daryl Maeda’s Chains of Babylon. The best study on the Asian American Movement’s origins and early ascent, it also brilliantly showcases U.S. cultural radicalism’s robust tradition.

While cultural radicalism can be defined variably, “one of its central characteristics,” according to cultural historian Jesse Battan, “has been the emphasis on subjective or personal forms of liberation.” Whereas political radicals “seek to regenerate society through the redistribution of wealth and political power,” cultural radicals “rely on the transformation of consciousness as their precondition for the creation of the ideal society.” By using Battan’s formulation to guide our reading of Maeda’s riveting volume, we can arguably better assess its nature and measure its significance. At the same time, however, we need to be mindful that “cultural politics” transcends the narrow formal boundaries of both “culture” and “politics” and encompasses, as media scholars Ian Angus and James Davison Hunter have noted, “the complex process by which the whole domain in which people search and create meaning about their everyday lives is subject to politicization and struggle.”

Maeda’s introduction (“From Heart Mountain to Hanoi”), draws on the historical experience of Sansei Pat Sumi, a late 1960s/early 1970s “luminary,” to manage his book’s fundamental burden: explaining how Asian American radicals during this interval, such as Sumi, “challenged prior ideas about their race and national belonging and articulated a new form of Asian American identity as a multiethnic racial formation” (pg. 2). Maeda uses the introduction as well to interpret Sumi’s 1970 Gidra poem “To My Asian American Brothers” in relationship to the line within it—“Chains of Babylon/bind us together”—that inspired his book’s striking title. What Sumi meant by Babylon, clarifies Maeda, was American racism and imperialism, the twin chains binding Americans of all Asian ethnicities together along with those Asians “struggling against American hegemony in Asia” (pg. 9).

Before delineating the development of a new Asian American consciousness through four diverse yet overlapping and interpenetrating case studies (chapters 2-5), Maeda devotes his first chapter, “Before Asian America,” to two tasks: 1) surveying the racialization of Asians in the pre-1960s-1970s U.S. through the dynamics of discriminatory immigration policies, legal and legislative measures, and socio-cultural representations; and 2) depicting how Asian groups countered this oppression through Asian-specific nationalism, assimilationist Americanization, and the twin “Old Left” stratagems of labor unionism and political progressivism.

Maeda assigns to each of his strategically selected and astutely titled case studies a primary theme to exemplify within his comprehensive multi-faceted thesis. Thus, chapter 2 (“‘Down with Hayakawa!’ Assimilation vs. Third World Solidarity at San Francisco State College”) accents Asian Americans’ struggles against whiteness; chapter 3 (“Black Panthers, Red Guards, and Chinamen: Constructing Asian American Identity through Performing Blackness”) highlights the rise of Asian American identity relative to blackness; chapter 4 (“‘Are We Not Also Asians?’ Building Solidarity through Opposition to the Viet Nam War”) stresses how Asian American opposition to the Viet Nam War nurtured transnational compassion for Asians in Asia; and chapter 5 (“Performing Radical Culture: A Grain of Sand and the Language of Liberty”) emphasizes the enactment of Asian American identity through cultural performance.

Maeda’s thought-and-conscience provoking conclusion (“Fighting for the Heart of Asian America”), articulates and critically reflects upon what he perceives to be the tripartite legacy of the Asian American Movement: 1) the term “Asian American” embracing U.S. Asians of whatever ethnicity; 2) a usable past for visionary Asian Americans; and 3) a transnational perspective. On the one hand, Maeda is troubled by the corruption of “Asian American” from a politically charged progressive term connoting an oppositional stance toward capitalist exploitation into one now largely descriptive of demographic factors (e.g., race, ethnicity and nationality) and betokening a pragmatic accommodation to business practices enhancing individual advancement and maximizing profits.

On the other hand, Maeda is heartened both by the way activists in newer Asian American populations have located themselves within the radical tradition established by older Asian American radicals to renew and extend their dream of a more just world, and by the deepened commitment by Asian Americans in the current era of globalization to think and act progressively outside the box of national boundaries.

Chains of Babylon is a book that not merely treats readers to a clear, colorful, and absorbing account of how the Asian American Movement was socially constructed, but also signposts in a broad sense what is required now and in the future to redeem and revitalize its revolutionary promise.

* * * * *

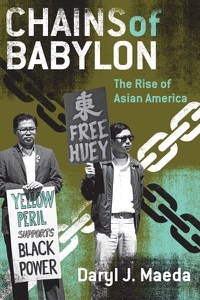

CHAINS OF BABYLON: The Rise of Asian America

By Daryl J. Maeda

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009, 224 pp., $20, paperback)

*This article was originally published in the Nichi Bei Weekly on July 25, 2013.

© 2013 Arthur A. Hansen / Nichi Bei Weekly