Read Part 1 >>

AL: Well, in terms of making a queer relationship visible, one thing that really moved me about your work was how rigorously documented it is. When I’ve read Noguchi in the past, I always thought there was something a little “queer” about his poetry, but seeing all the letters and observations you’ve unearthed makes his relationship with Charlie really come to life again. So much of queer history is about reconstructing what’s lost or can never be fully known, but there’s something very moving about seeing a very well-documented account of a queer relationship in the past.

AS: So I consider myself a queer historian, a historian of queer studies, as well as Asian-American studies. Typically what happens in queer history of pre-Stonewall, even pre-‘30s history, is that any writing becomes speculative. In histories of marginalized communities, they say that oral histories are the best method, but when people are dead, you can’t interrogate them and ask, Were you gay? Were you queer? Did you have sex? You can’t ask these questions. Not only can you not collect oral histories and ask direct questions, but also you have to account for the fact that people have done everything in their power to destroy all the evidence that they were queer.

I wanted to write a history that was more than speculative. That just said outright that Yone and Charlie were queer. So that’s part of what of I did, very conscientiously, as I documented the relationship between these two men.

AL: Can you talk a little about your process as a historian working on this project? What archives did you go to? How long did it take?

AS: It took me about four years to gather all the evidence. Then, I mapped out all the evidence in a way that made sense as a compelling argument.

For example, I would see a letter between Charlie and Yone, and it would be passionate, but I would have to figure out if it was more passionate than other letters. Was this letter more than “just friend” passionate? So then I would read all of Yone’s letters to his other friends, and compare these letters to his letters with Charlie. These are the kinds of things I would have to do to make sure that I could prove that his relationship with Charlie was special and unique. I did the same things with Charles as well. I read his letters to other people, and then read what he wrote to Yone.

I think Charlie’s affection for Yone is pretty complicated. I think Charlie was really in love with Kenneth [a younger white man who lived with Stoddard for several years]. But he couldn’t really have Kenneth, and I don’t think Charlie ever really took Yone seriously. I’m sure he thought he was hot, but I think he really wanted to spend his life with Kenneth.

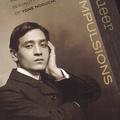

AL: Just to comment on how hot Yone was; whenever I show people a copy of your book, they look at the front cover photo of Yone and almost everyone is like, “Wow, he’s really hot.”

AS: <Laughs> When I got the proofs for the book, I showed some people the cover, and all the straight women I showed the cover to were like, “Oh my gawd, he’s gorgeous!” Yeah, all the straight women were falling over themselves.

AL: <Laughs> What about the gay men?

AS: They didn’t really say anything. They were just kind of silently appreciative. Maybe because I’m not a gay boy, and they didn’t feel comfortable saying anything to me. Anyways, it’s really funny that back in the 1890s too, all these white women saw him and wrote about how good looking he was.

AL: So back to Charles and Yone for a moment; do you think their relationship was somehow unequal, or one-sided, where Yone was looking for more than Charles really able to give?

AS: I do think that by 1900, when Yone went to live with Stoddard in the Bungalow [Stoddard’s home in Washington, DC] in 1900, that he expected something more. Then Yone gets kind of fed up. He decides that he doesn’t want to hold Charlie’s hand while he’s crying over Kenneth. And so Yone leaves.

I also think that Yone was deeply conflicted about the public appearance of his relationship with Charlie. He would write all these affectionate letters to Charlie, but when Yone was writing to women, he would downplay his affections for Charlie. Even if he really wanted to be with Charlie, there was a part of him that couldn’t.

AL: And that part, what do you think that part was?

I don’t know. Part of it is this immense pressure to get married. I also think that Yone was one of these men who’s constantly worried about what other people think of him. And people are already talking about Charlie like he’s a little too unacceptably friendly with men. He’s this Asian guy trying to make it in a white world that’s super racist. And he’s just trying to find love, too. It’s hard enough, even without all this social pressure, to find love.

AL: In a different vein, I have a question about how you see the intersection of queer studies and Asian American studies in your work. One way into this question is that the Discover Nikkei website has this interesting definition, actually, more of a question: “What is Nikkei?” And the point of this definition/question is that the term Nikkei, like queer is pretty fluid, constantly shifting depending on who is using it and in what historical and social context. In your book you talk about not being that interested in whether or not Noguchi was gay, or bisexual, or whatever, but what’s the political force and historical value of using the word “queer” to describe his relationships and compulsions?

AS: So, on the one hand, I’m using the term “queer” in the broader sense—of kind of “odd, unconventional” but at the same time I’m very vigilant about the ways that “queer” gets appropriated in the academy. As queer theory and queer studies become more mainstream, everyone wants to queer everything! And then actual queers kind of get the shaft—all of the sudden the straight academic who queers straight stuff is revolutionary. I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t want to put queer on something that wasn’t actually queer in some way. I’m balancing, I’m walking on this line between using queer in the broadest way—meaning odd, but also queer as a way of signifying “same-sex intimacy.”

AL: This problem of the usage of “queer” is interesting because at the turn of the century, heterosexual relationships between Japanese men and white women were often seen as “queer” and deviant. So even though those relationships weren’t founded on same-sex intimacy, they’re arguably a kind of queer relationship.

AS: Yes, and those relationships were illegal in the state of California. Folks aren’t so happy about these relationships. In the 1890s, these relationships are seen as “odd” and stories of interest. But by the 1910s, there’s a perception that there’s something morally wrong about them.

AL: Thanks so much for the interview. It was a pleasure to read your book, and I look forward to seeing your next one soon.

AS: Thank you!

* * *

BOOKS & CONVERSATIONS

Queer Compulsions: Race, Nation, and Sexuality in the Affairs of Yone Noguchi by Dr. Amy Sueyoshi

Saturday, January 19, 2013 • 2PM

Japanese American National Museum

Los Angeles, California

© 2013 Andrew Way Leong