I think most people have a collection of odds and ends they keep as old keepsakes from their parents or grandparents. Heirlooms of long forgotten nostalgia gathering dust in a drawer or in an old shoebox. Blurry reminders of things past, whether they are happy or sad moments.

When I was only six years old, my mother gave me her old pencil box from when she was a child. Perhaps paralleling my age. Her grandmother gave it to her as a birthday gift.

Like me, my mother liked to draw, and was in fact a fairly good artist. She always wanted to be a commercial artist when she was younger, but her mother put the kibosh on that.

“You can’t be an artist,” her mother told her. “Artists are crazy or they go crazy.” My grandmother believed that all artists wound up like Van Gogh. My mom told grandma that being a commercial artist was nothing like a “fine artist.”

“No” said her mother. “Better to find a job in a factory where you can be of practical service.” My mom ended up working for National Cash Register as a technician.

The pencil box is made of cedar with a sliding lid. On it is a picture of a Japanese girl playing tennis or holding some sort of racket. How that relates to pencils and such, I have no idea other than the illustration was of a schoolgirl. I guess in Japan, they stressed the ability to ace a tennis serve and be able to record the score. Thirty-love.

My mom was born in 1929 in what is now Monterey Park, California. Back then, the area was known as Hellman’s Ranch. And to the locals, “Coyote Pass,” as there used to be an old cow path that followed down through the hills and dead-ended at Atlantic Avenue. The entire area of East Los Angeles, in fact all land outside the immediate downtown area, was farmland as far as the eye could see.

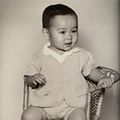

My mom as a baby growing up on a farm in what was known as Coyote Pass or Hellman's Ranch. Unincorporated East Los Angeles. (Now known as Monterey Park, CA) Circa 1930.

Her family moved to Coyote Pass in the early 20s after a few years in Fresno picking fruit. But my grandparents were born in Hawaii. This was around 1885. My great grandparents had emigrated from Hiroshima, and Oahu was their first stop as they moved east across the Pacific.

There was plenty of work to be had cutting sugar cane. Backbreaking work under a relentless tropical sun. My granddad would talk about the big black cane spiders and how his own parents slaved away toiling in the fields.

My grandfather, George Baba. Nisei. Born in Hawaii in 1892. He's standing beside his Ford Model A Sedan (on the farm located in Coyote Pass/Hellman's Ranch) Date, circa 1930.

Life in Los Angeles was somewhat easier, but no less strenuous. My grandparents were able to save up enough money to buy a farm. Twenty acres of land where they grew produce for the Central Market to sell. Since my grandparents were U.S. citizens, they could own land. Under the Alien Land Laws, non-citizens were prohibited from owning property.

My mom was the youngest of five children. Her grandmother from Hiroshima lived with them in a drafty farmhouse my grandparents built. My great grandmother would occasionally travel back and forth from Japan to California.

On one trip, great grandma bought the cedar pencil box for my mom. Mom would take it to school as a dutiful student.

Sunday, December 7, 1941, everything changed.

Imperial Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor.

Come Monday, my mom was back in school. She would have been about thirteen. There was dark heavy pall that hung over the classroom. Everyone obviously knew what happened. My mom recalled hearing her teacher in the hallway that morning telling the principal, “I don’t want those stinking Jap kids here today. I want them gone, or I’m leaving!”

My mother was devastated. She began to cry. Her teacher, who was Caucasian, before the bombing seemed like a nice, decent woman—caring and professional. But it was clear now that my mom and the rest of the Japanese American children were different. Not Americans, but alien combatants. “Yellow devils.”

Understandably, tensions were high as well as emotions. The country was at war. And my family was caught in the middle—innocent victims of the terrible fallout.

My family was born and bred in America. By 1941, they had lived in this country for over fifty years as citizens. But none of that mattered. On February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 was signed. All Japanese Americans, or anyone of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast, were to be relocated from their homes and put in internment camps.

My granddad sold the farm for pennies on the dollar. The house, the car, the tractor, the livestock, everything either sold or abandoned. My mother, her siblings and her parents were allowed only to take what they could carry when they were evacuated.

For my mom, that included packing her beloved pencil box in her suitcase, all that was allowed on the train that took them on an 800 mile train trip from Los Angeles to Heart Mountain, Wyoming. All under the watchful eyes of armed United States Army soldiers.

My grandparents family farm. As a Nisei, he owned the land. This what Monterey Park (then, Coyote Pass/Hellman's Ranch) looked during the 1930s. Looks like corn planted. In the far distance is Atlantic Avenue.

Heart Mountain lies in the northwest corner of the state in a desolate semi-arid area. No trees. Just flat, dusty nothingness. But rising above was Heart Mountain. I assume people thought the peak resembled a heart shape. How ironic to be held captive in a place with a name like Heart that could be completely heartless.

As you can imagine, the winters there were brutal. Families were housed in a simple frame of two-by-fours, and one-by-six walls sheathed with tarpaper. No insulation. The buildings were raised off the ground, but the cold wind would blow through the cracks in the shoddy floor planks. Temperatures in the winter would be 17 degrees below zero, and only small pot-bellied stoves heated the long barracks. There were no walls separating each family. Just a bed sheet for a curtain.

My uncles joined the U.S. Army and left the camp to fight the Imperial Japanese. My eldest aunt left and moved to Minneapolis (family members could leave camp as long it was east of the Mississippi). But the rest of the family stayed put until the end of the war. Three long years in what amounted to prison if not torture.

During the winter the wind would blow the snow in horizontally. Complete white outs. And in the summer, Heart Mountain could easily get into the 90s and 100s. The entire area was desert. (You’d expect pine forest. Not here.) Dust would swirl around the barracks getting into nearly everything. Including food. All adults were expected to do work detail. My mom and her sister attended school.

Finally on January 2, 1945, an order was handed down to close the camps. My mom, aunt and grandparents returned to Coyote Pass.

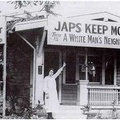

They returned to nothing. The farm was gone. The person who bought it had begun to subdivide it and homes were in stages of being built. But signs read everywhere, “No Japs” and “Japs go home.”

Home? My family was home. Yet they were homeless. Literally. They had no place to go.

Picture of my mother. Kazue Baba Toyoshima Taken just after high school. Graduated from Long Beach Polytechnic. (Same school I graduated from).

Eventually they found temporary housing in Long Beach, a service provided by the U.S. Government. By now, my mom was ready to enter high school, and she attended Long Beach Polytechnic. The same school I went to.

My dad’s family was imprisoned in Manzanar during the War. A dusty arid nowhere in the middle of Owens Valley, just below the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

My own dad and his brothers were in the U.S. Army fighting the Imperial Japanese. My father remained in the Army throughout the war and during the U.S. occupation of Japan. He also stayed on during the Korean War.

As chance would have it, both my mother’s family and my dad’s family were at one time neighbors in Coyote Pass. My dad is seven years older than my mom and didn’t really know her back then. But after dating my mom’s older sister for a while he ended up getting fixed up with my mom. Well, I guess romance bloomed and they were married in 1957. I was born in 1960.

I was six years old when my mom presented me with this odd cedar box. The pencil box from her childhood she managed to keep for over thirty years. Through war and hardship. Pain and poverty. I took the pencil box and just stuffed in a shoebox and into a closet. It had a picture of a little Japanese schoolgirl on it, and it seemed rather “sissy” (pardon the word) to me. I never used it.

If I wanted a pencil box, I wanted something masculine on it. Something with army men or racecars. Even a cowboy. (In the early 60s, boys still wanted to be cowboys). So the little box gathered dust in a closet for decades. But I knew it was important. Kind of. So I never threw it away. I knew it meant a lot to my mother.

Years had passed. I graduated from high school and college, worked as a high school teacher and quit, and then entered the “fabulous” world of advertising. I met a girl at work and fell in love. I gave her the pencil box as a token of our friendship and love, the most valuable thing that I could give. Something that had endured so much love and so much pain, but a symbol of strength and eternal hope. It held so many things yet it was completely empty.

Time passed and I moved to Chicago. My brief relationship with that girl had ended, and a new life waited for me in the Windy City. Nearly a decade had passed, as I now became a Chicagoan. I even adopted a Chicago accent without realizing it: “Da Bears. Da Bulls.”

But on Wednesday morning, October 10th, 1998 I got a call from my little brother in Long Beach. I was in my office at the time. My brother, in a soft voice, gave me the terrible news. My mom had died that morning from a massive stroke. I had just spoken to her a week before. She seemed fine. She always asked how I was doing. How was work? Was I seeing anyone?

“No ma, I’m still a loser,” I talked to her once a week, all the years I was away from home. Now she was gone. Forever. I took an emergency flight back to Los Angeles and helped with the funeral arrangements.

I buried my mother on a bright sunny fall day. In her open casket, I placed several dozens if not more of cattleya orchids in with her, all from plants that grew in my greenhouse. I also placed an old photograph of my mom holding me when I was just a newborn. And a personal letter to her. The funeral director closed the casket and lowered her into the ground. And that was that. I’d never see her again. Never talk to her. Never hear her laugh.

I returned to Chicago and went back to work. Life went on as usual. One day, I received a package in the mail. It was addressed to my office.

I opened it up and there was my mom’s old pencil box. My old girlfriend had heard of my mom’s passing and returned it to me. What a long and winding trip this little box had taken. Now it was “home.” I’m sort of glad that I didn’t have it at the time of her burial. I might have placed it in the casket with her. It was hers. And was a part of her life for over 65 years.

But now I had it back.

It’s a loving reminder of her life, and everything she had to endure. That little cedar pencil box with the sliding lid and a picture of a Japanese schoolgirl on it. Something that I initially disliked. But now treasure.

* This story was originally published by KPCC National Public Radio.

© 2012 David Toyoshima