I didn’t eat much Japanese food growing up. Born hapa Yonsei of a second generation German American mother and third generation Japanese American father who’d grown up together in the “old neighborhood” of Lakeview, Chicago, circumstances didn’t dictate much knowledge of overt Japanese customs, culinary or otherwise.

Our family emigrated from Kyushu in the early 1900s, farmers who plied their trade in California’s Central Valley, culminating in ownership of acreage purchased under the names of their American-born Nisei infants due to the California Alien Land Law that prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land or even leasing it for a period exceeding three years. “Jus Soli” provided them a loophole whereby they could eventually own property some twenty years post-arrival.

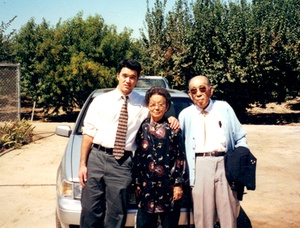

My Nisei grandparents were raised in the neighboring communities of Fowler and Del Rey, roughly ten miles south of Fresno, CA. Post-evacuation, from the Gila River War Relocation Center they further relocated to the Midwest, where they were officially advised to not congregate among other Japanese Americans. On a personal level, they felt the insular Japanese communities of their West Coast upbringing—although social conditions of the day did not provide for integration—contributed to the conditions leading to Executive Order 9066, and as such they had no ambition to reassociate with the larger JA community. Although they grew up speaking Japanese, in their quest to provide their offspring with a “true” American upbringing, they never spoke it to their children. My mother’s parents who had emigrated from Germany pre-WWII—and particularly since my grandfather had fought for the Kaiser’s army during WWI—never spoke the German language to their children for the same reason.

To appease my father, my mother did mostly cook rice for our meals instead of potatoes, and that was about it. We never went to Japanese restaurants. When West Coast family came into town we went out for China Meshi. JA family funerals were concluded over China Meshi. And the times I can remember visiting relatives on the family farm in Fowler during my childhood, my Nisei aunts cooked…Mexican food.

My grandmother once told me that aside from the inaka-style okazu dishes they grew up on, because they worked side-by-side in the fields with Mexican laborers and would trade recipes, most Japanese in their community knew how to cook Mexican dishes. Special days at my bachan’s house in Chicago were when we walked into her cooking up a batch of enchiladas or tamales. I often wonder if they altered the recipes for their palate or if nostalgia clouds my taste buds, because I’ve never tasted Mexican food from either a restaurant or prepared by Mexican family friends or coworkers that carried the same flavor as California inaka Nisei adaptations.

To this effect, I wonder if Mexican culinary traditions within the California Japanese American agricultural community couldn’t be considered Nikkei cuisine. Because as a disconnected Midwestern JA lacking any sense of a Japanese upbringing, although I was privy to my Nisei grandmother’s inaka-style Japanese American “slop” handed down from her mother likely from the nethers of the southwestern Japanese countryside, my taste memories of what I consider our family’s JA roots are found in the kitchen booth of a Fowler farmhouse over a plate of homecooked red sauce enchiladas with freshly picked apricots for dessert.

*This article was originally published in Voices of Chicago, online journal of the Chicago Japanese American Historical Society on July 3, 2012.

© 2012 Erik Matsunaga