Read Part 1 >>

There are other pet stories that turned out happier. Before the war, Jack Muro and his parents were farmers in Winters, California. The dog of a neighboring sheepherder family had a litter of puppies. They offered the Muro family the pick of the litter. The Muros named their chosen pup, Poochie, who grew up as a much-loved family member. After Jack graduated from Winters High School, he moved to Los Angeles to work with an uncle in the produce market. Later, his parents followed along with Poochie.

When the U.S. declared war on Japan following the Pearl Harbor attack, the Muro family—as was permitted then—voluntarily moved back to Winters. They, like many others, believed that by moving out of Military Zone 1, they would not have to be relocated and imprisoned. As fate would decree, the U.S. Army “changed its mind” and ordered the evacuation of all Japanese from the three western states: Washington, Oregon and California, regardless of the huge effort and expense the families made to move inland to Military Zone 2. Doggone it!

The Muros had to place Poochie into a kennel in Winters because they were soon to be “impounded” themselves in the Merced Assembly Center, a fairground with hastily built prison barracks. This unprecedented government action was happening to all Japanese in all three of the western states; that of being forced into 17 similar assembly centers quickly setup to stockade us while more permanent prison camps where being built throughout the “badlands” of the USA.

Along with 4,500-plus Japanese Californians, the Muros were held there in the MAC for almost six months until they were sent by train to Granada, Colorado in September 1942. There, they were 1,873 miles away from Poochie, shown in the photograph (above) taken the day Poochie was placed in the kennel. To me, in that photo, he seems sad already, knowing that he was being left behind. Six-months later, I can imagine Poochie still wondering where his family was.

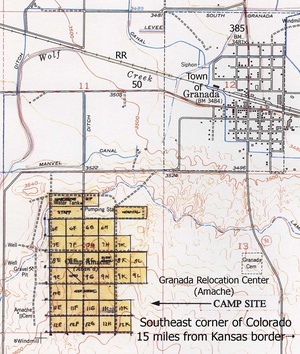

The name of the War Relocation Authority, Granada Relocation Center was changed to Amache to solve the confusion that occurred with two postal delivery sites near each other having the same “town” name that caused the existing Granada Post Office to be overwhelmed. The map shows their close proximity to each other.

The camp director of Amache, James G. Lindley, had the reputation of being one of the more lenient and considerate project directors out of the ten WRA Relocation Centers. His administration officially allowed pet dogs in camp. This is evident in a nine page ordinance drawn-up by the Amache community council with Lindley’s approval in April, 1943. A full page was dedicated to rules for dog ownership.

Also, in a Chronological History of the WRA Granada Project (Amache) that highlighted notable occurrences on a daily basis from June 1942–August 1945, there were two cites that addressed dogs: June 16, 1943 noted: “Dog licenses for Amache canines on sale at office of Police Chief” and, July 28, 1943: “The killing of 50 chickens on the Center farm by stray dogs brings warning to dog owners.”

In her novel, Julie Otsuka wrote, “Hungry coyotes crept in under the barbed-wire and fought with stray dogs over scraps of food.” Her novel was based on Topaz, the WRA camp in Utah. Although, when my grandson and I went tent camping in 2008 on the very barrack site my family lived in Amache, we heard coyotes yelping as the sun began to set. Min Tonai, former President of the Board of Directors of the Los Angeles Japanese American Community and Cultural Center, former member of the Board of Trustees and chair of various committees of the Japanese American National Museum, and president of the Amache Historical Society said, “I remember coyotes howling at evening or night, particularly in the summer and autumn.” Makes me wonder, though, maybe it was coyotes that killed the chickens and not the dogs?

Hyosaku Shitara of Gardena, California owned two German Shepherds Queenie and Whitey. They were driven all the way to Colorado by Virgil Wallace, his Caucasian son-in-law, who was outside of camp at the time. He then voluntarily joined his wife, Tsuruko “Toots” inside Amache as a registered internee. Cute Carlene (Tanigoshi) Tinker is shown with Queenie in the photograph (R). Carlene is the granddaughter of Hyosaku Shitara and the niece of Auntie Toots. The Wallace’s lived in the next unit of the same barrack, that the Tanigoshi family lived, so Carlene got to play with Queenie and Whitey often.

Min Tonai offered another interesting tidbit. This he heard from his mother, “an Issei woman had a toy dog (lap dog) in Amache and was caught bathing the dog in a bathtub that the block’s residents had build for infants and small children. When the mothers objected to her on using the bathtub, she is reported to have said, “My dog is cleaner than your snot-faced kids.”

The late, Tsuru “True” Shibata was one of the early arrivals of an advance party recruited to help get the camp ready. She had her pet dog sent by train to Amache from California. Shortly after the war, she met and married Min Yasui. It was Min Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi who separately refused to comply with the curfew laws imposed on the Japanese Americans and were arrested and served jail time.

They along with Fred Korematsu, who refused to enter an assembly center and also served jail time, became legendary icons of the legal battles against the U.S. government for the injustices against them and the illegal actions committed against the U.S. Japanese community at large. It took over forty years, but they eventually prevailed when their wrongful convictions were overturned by the courts. Their cases and the hard work of the many activists from the Japanese American communities helped pave the way for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1988 and the Redress and Reparation for all the surviving internees.

There are many other stories about young internees adopting the local wildlife as pets, such as the desert tortoise, lizards, salamanders, snakes, scorpions, and a bird as in Shig Yabu’s Hello Maggie, a magpie that fell from a tree in Heart Mountain. My uncle’s sister, Margarette (Masuoka) Murakami, of Santa Rosa told me that, as an Amache teenager she was given a kitten. I heard that some stray dogs were adopted when they wandered into camp under the barbed wire fence from the outlying countryside.

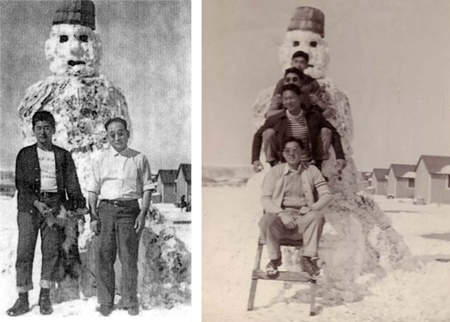

The Muros were finally able to arrange for Poochie to be transported to Amache. Jack remembers thinking, “how scared Poochie must have been in the dog cage on the long lonely and noisy train trip.” The Muro family surely had a wonderful reunion when at last he arrived. For his part, Poochie must have been beside himself with ecstasy. Poochie is shown standing on his hind legs assisted by Jack next to his father, Tokoichi, in front of a huge snowman (photo: bottom left) that was built by Jack and his buddies (photo: bottom right). Jack recalled that his father worked in the camp police office and must have taken care of buying Poochie’s dog license. Poochie added much love to the Muros’ remaining two-years in camp.

After the war, the Muros returned to Los Angeles to restart their lives. Jack married Kate Kei Tanji, of Livingston, sister of his best friend in camp, Taro Tanji. Jack didn’t court Kate in Amache, but they got together after their release and lived a happy life in Los Angeles with Poochie until his natural end. Jack and Kate have two children, Jeanne and Allen, who were not old enough during that time to remember Poochie.

The Shitara family was also able to take their dogs home after being released from camp. Dell Shitara, Carlene (Tanigoshi) Tinker’s cousin, wrote about going home to Los Angeles after the end of the war, “The U.S. Government paid for their (Queenie and Whitey) passage via the train.”

Today, Carlene said “When John (husband John Tinker) and I stopped at Manzanar, two years ago, we were struck by the display that had a sign, “No dogs allowed.” We knew better!”

Sadly, it was the unfortunate fate for many families who weren’t able to have their pets in camp and who were denied the same happy experiences as shared by the Muro, Tanigoshi, Shitara, Shibata, and—I’m sure—other lucky families.

Those families who had to leave their pets behind in the confusion and fear of what lay ahead, never imagined that they could have made arrangements for their pets to join them later. To this day, those surviving family members who were deprived of their pets still carry the emotional scars of their forced separation from their beloved pets. Doggone it!

Author’s Notes: I am indebted to my friend, author Alfred Strohlein of San Diego who helped to make this a much better article than without his patient assistance. I’m also grateful to all who are mentioned in this essay for their contributions and help to tell the sidebar stories of how painfully impactful the WWII evacuation and imprisonment was.

All the books mentioned in this essay are available in the JANM store and online: janmstore.com

If you have any stories or pictures of pets in camp, please share them with me or please add your comment below. Thank you. garyono@sbcglobal.net

© 2012 Gary Ono