It galled many long-standing Japanese American Citizen League (JACL) members who read the “Millennium New Year’s Edition” of the Pacific Citizen (PC), the League’s newspaper, to encounter “Influential JA Journalist: James Omura” in an issue commemorating outstanding twentieth-century Nisei.1 Perhaps no other Nikkei name could so predictably have nettled Old Guard JACLers as Jimmie Omura, born on Bainbridge Island, Washington, in 1912 and died in Denver, Colorado, in 1994.

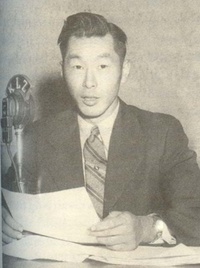

Jimmie Omura, "Rocky Shimpo" editor, appeared on radio station KLZ in Denver on October 12, 1947, to inaugurate a new series, "Liberty Calling," designed to deepen public understanding of minority group issues in Denver. (Photo courtesy of Gregg Omura)

Thus, JACL pioneer Fred Hirasuna wrote in the PC:

Who named James Omura influential journalist of the past century? Omura…did not challenge evacuation by physically resisting evacuation [but avoided it]…by leaving the area [West Coast] in March of 1942. His main claim to fame seems to be that he supported the Heart Mountain draft resisters and castigated the JACL for not doing the same.

His record pales when compared with that of Bill Hosokawa…[or] Larry Tajiri… If any one person deserves the title of leading journalist, my choice would be Bill Hosokawa, and he would be the choice of the majority of JAs who actually experienced the evacuation and internment.” 2

Certainly a case could be made for Larry Tajiri, the PC’s 1942-1952 editor.3 Possibly, Hirasuna’s reason for ranking Hosokawa over Tajiri is tied to his rationale for depreciating Omura. While Seattle-born and bred Hosokawa was imprisoned at Washington’s Puyallup Assembly Center and Wyoming’s Heart Mountain Relocation Center, Tajiri did not “do time” in a concentration camp. Instead, he departed California on the final day of “voluntary evacuation” to “resettle” in Salt Lake City.

That same day, March 29, 1942, Omura left the Golden State for Denver, the other intermountain mecca for voluntary migrants. A Bay Area florist, Omura was publisher-editor of the Nisei magazine Current Life. If his 1930s sidekick Tajiri planned to convert the PC into a weekly,4 Omura determined to resume publishing the politics and arts monthly he founded two years before in San Francisco.

Likely Hosokawa’s stellar Denver Post career from 1946 to 1992 made him Hirasuna’s choice. Stridently anti-Japanese during wartime, the Post afterwards so liberalized as to embrace Hosokawa and, later, Tajiri.5

World War II-era Denver, with 325,000 residents, was a relatively favorable place for Nikkei. Located in the “free zone” near four War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps,6 Denver attracted voluntary resettlers like Omura, as well as those, like Oregonian Nisei curfew resister Minoru Yasui, who resettled there from a WRA camp. Denver’s wartime Nikkei population peaked at 5,000, even though the WRA clamped a 1943 moratorium on resettlement there.7

Colorado’s 4,000 Japanese Americans was the largest such prewar population for non-Pacific Coast states, but only 700 lived in Denver. There a several-block transitional area around Larimer Street formed a Japantown. In Denver, racism was not unremitting as it had been for prewar coastal Nikkei.

Likewise, Denver was a favorable place for Nisei journalism. As David Yoo observes, the expanded readership of Nikkei migrants to the intermountain region “breathed new life into the struggling English-language sections of three…papers outside the restricted zones: the Rocky Nippon, Colorado Times, and Utah Nippo.”8 The first two were published in Denver. The Rocky Nippon (later called the Rocky Shimpo) inaugurated its English-language section in October 1941, while the Times followed suit in August 1942.9

The Rocky Shimpo appealed more to WRA-camp inmates than did the Times (for which Omura wrote in late 1942), and buttressed its masthead claim as the “largest circulated Nisei vernacular in the continental U.S.A.”The Times, whose publisher-editor was veteran Issei Denverite Fred Kaihara, resonated more with resettlers in burgeoning Midwestern cities, namely Chicago, which until mid-1947 lacked a vernacular newspaper with an English-language section. The early postwar addition of columns by Togo Tanaka, the prewar English-section editor of Los Angeles’s Rafu Shimpo and one of Chicago’s 20,000 plus resettlers, and Minoru Yasui helped the Times double its Denver rival’s subscriber base.

Scattered evidence suggests that the two papers experienced a reversal in popularity from the wartime to the postwar years, probably because the Nikkei readership inside and outside of the Denver region changed from anti-JACL to pro-JACL. Indeed, Omura’s shifting journalistic fortunes in Denver between 1942 and 1947, which led to his “banishment” from Nikkei life and letters until the 1980s, dramatize this transformed ideological climate in Colorado and throughout Japanese America.

This essay first treats this World War II and immediate postwar transformation in terms of the Omura-JACL battle. It then fast-forwards three decades to consider Omura’s resurrected role as a Nikkei writer and outspoken JACL critic after testifying at the 1981 Seattle hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) and achieving community validation within the Seattle-originated National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR).

* * * * *

By Jimmie Omura’s Denver arrival on April 2, 1942, the JACL leadership saw him as their primary nemesis. Their mutual animosity began when a 1934 article in the Omura-edited New World Daily News of San Francisco--which seemingly impugned the integrity of a Placer County JACL leader--so provoked JACL founder Saburo Kido, a Nisei attorney for the rival pro-JACL Hokubei Asahi, that he threatened to sue Omura for slander.10 Omura and Kido, later the JACL’s wartime president, soon clashed directly when Kido interpreted Omura’s editorials criticizing “Nsei leadership” as attacking “JACL leadership.”

When the JACL’s 1934 national convention met in San Francisco, Omura was an established JACL critic. Omura’s newspaper had him welcome incoming JACL president and Japanese-American Courier editor Jimmie Sakamoto to the city. The two Pacific Northwest Nisei met four years earlier when Omura sought work on Sakamoto’s paper. Then the JACL’s founding father had patronized Omura, but now Sakamoto was reproachful. “He said,‘ Why did they have to select you?’ … I felt so insulted that I turned around and walked away.”11

Relations between Omura and the JACL came to a head in 1935 after the New World Daily and the Hokubei merged into the New World Sun. Both English-section editors, Howard Imazeki and Omura, managed a page. Omura wrote his own editorials, but Imazeki deferred to Saburo Kido’s “Timely Topics” column.

Before long Kido confronted Omura: “I’m being embarrassed… I write an editorial one way on the front page, and my friends say they flip the page and there’s an exact opposite editorial on the second page.”12 In early 1936 Omura resigned.

Up until October 1940 when Omura began Current Life, journalism and the JACL figured little in his life. Larry Tajiri, English-section editor of the Japanese American News and then staunchly anti-JACL, did get Omura to write editorial features. However, when Tajiri left for a New York post, Omura’s writing was censured and then discontinued.13

Omura’s Current Life editorials increasingly chastised the JACL: its leadership was feckless in not preparing Nisei for a probable United States and Japan clash; and its membership was reckless in partying at gala bashes instead of promoting social action. Moreover, the JACL’s prolonged accommodation to Japanese imperialism and its flamboyant eleventh-hour American flag waving bothered Omura. Finally, according to him, “shortly after or even before Pearl Harbor,” JACL leaders fingered him as a potentially dangerous person.14 While this accusation fell on deaf ears, the Omura-JACL war had heated up considerably.

Notes:

1. Takeshi Nakayama, “Influential JA Journalist: James Omura,” Pacific Citizen, 1-13 January 2000, p. 6.

2. Fred Hirasuna, “Letters to the Editor,” Pacific Citizen, 7-13 April 2000, p. 7.

3. Brian Niiya, ed., Encyclopedia of Japanese American History: An A-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2001), s.v. “Tajiri, Larry (1914-1965) journalist” by David Yoo. See also, Bill Hosokawa, “Larry Tajiri, A Better Choice, Pacific Citizen, 11-17 February 2000, p. 6

4. Bill Hosokawa, JACL in Quest of Justice: The History of the Japanese American Citizens League (New York: Morrow, 1982), 156-57, 178-79.

5. Bill Hosokawa, Out of the Frying Pan: Reflections of a Japanese American (Niwat, CO: University Press of Colorado), especially “Hosokawa of the Post,” Chap. 8, 63-79.

6. Minidoka (Idaho); Heart Mountain (Wyoming); Topaz (Utah); and Amache (Colorado).

7. Russell Endo, “Japanese of Colorado: A Sociohistorical Portrait,” Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31 (Fall 1985): 100-110.

8. David K. Yoo, Growing Up Nisei: Race, Generation, and Culture among Japanese Americans of California, 1924-49 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 129.

9. Ibid, 130.

10. James M. Omura, interview by Arthur A. Hansen, “Resisters,” pt. 4 of Arthur A. Hansen, ed., Japanese American World War II Evacuation Oral History Project (Munich, Ger.: 1995), 209-11.

11. Arthur A. Hansen, “Interview with James Matsumoto Omura,” Amerasia Journal

(1986-87): 104.

12. Ibid, 104-5.

13. World Biographical Hall of Fame (Raleigh, NC: Historical Preservations of America, 1992), s.v. “James Matsumoto Omura.”

14. Omura to Hansen, “Resisters” 254.

* Arthur A. Hansen, “Peculiar Odyssey: Newsman Jimmie Omura’s Removal from and Regeneration within Nikkei Society, History, and Memory” in Louis Fiset and Gail Nomura, eds. Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005, pp. 278-307.

@ 2005 by the University of Washington Press