Referred to as the camp for “troublemakers” and “bad” and “disloyal” people, Tule Lake’s reputation still carries stigma for those who were incarcerated there. The stigma remains so pervasive that most Nisei who refused to answer “yes” to the so-called “loyalty questionnaire” questions 27 and 28 some 65 years ago don’t like talking about what one Nisei referred to as Tule Lake’s “dirty linen.”

On December 5, 2008, President George W. Bush acted to change all that, designating the Tule Lake Segregation Center as a National Monument. The Monument designation transformed the so-called “dirty linen” into a valuable historical lesson about 12,000 persons of Japanese descent who responded to injustice with protest and resistance.

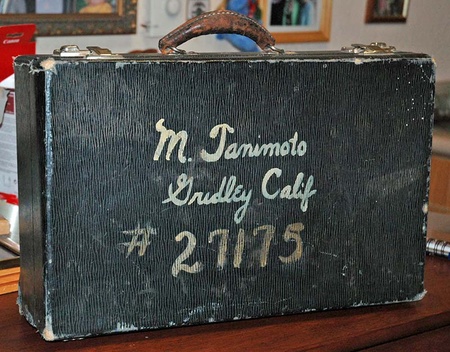

One Nisei who was gratified to learn of Tule Lake’s National Monument status was Mamoru “Mori” Tanimoto, age 88. Tanimoto’s father was a landowning farmer in Gridley, near Yuba City, Calif., who grew rice and peaches before the war. Turning 22 years of age on the day his family was forced to leave the family farm for Tule Lake, Tanimoto was 1A (draft eligible), but in Tule Lake found that he was reclassified to 4C (enemy alien). Months later, when he was expected to answer the loyalty questionnaire, Tanimoto had little enthusiasm for proving anything to the government.

Tanimoto and his older brother Masashi were among the approximate two to three dozen Tule Lake dissidents who lived in Block 42 and were jailed en masse for refusing to answer the loyalty questions that were used by the Army and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to cull the so-called “loyal” from the “disloyal.” The dissidents spent a week imprisoned in the Klamath Falls and Alturas jails followed by a month at the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp on Hill Road in Siskiyous County, a few miles from the town of Tulelake and the Tule Lake Segregation Center site. The CCC camp is included in the Tule Lake National Monument that will be administered by the National Park Service.

The government’s loyal/disloyal paradigm forced on Japanese Americans contributed to a post-war suppression of stories of protest in the camps, say scholars and activists working to tell the stories of Tule Lake. Consequently, legitimate and courageous acts of grassroots civil disobedience were shunned in favor of stories that enhanced an image of Japanese American loyalty and cooperation.

After decades of silence about his experience as a Block 42 dissenter, Tanimoto recently opened up about why he took the risk of protesting the loyalty questions. “I started thinking about it. This is a free country, or supposed to be,” he said. “So, I said, ‘Heck no. I ain’t gonna sign it.

“We talk about freedom and justice and all that. Well, we had no freedom. We had no justice. The Constitution guarantees us freedom of speech; we didn’t have that.”

“People Weren’t Afraid”

Tanimoto downplayed the courage it took to refuse cooperation with the government’s demand to prove loyalty. His explanation, “Ahhh, just hard headed, I guess—[we] decided we’ll fight the government.”

Tanimoto described weeks of harassment by the WRA, trying to get the protesters in Block 42 to answer the questionnaires. “WRA keep on coming back. Every time, we said no. They tried to make us sign,” he said. “There were 22 or 23 of us that said we won’t sign. WRA threatened us, but we stayed firm and for this, the Army came and arrested us.”

The Army could not make the young men budge from their principles.

“Each individual decided on their own,” Tanimoto said, describing a widespread grassroots rebellion among the Block 42 residents. “The WRA threatened, ‘something bad gonna happen to you.’ And finally, they say, ‘you’re gonna go to jail.’ And, that didn’t stop us.”

“We just decided not to answer [questions] 27 and 28,” said Tanimoto. “Each just decided on their own. Nobody forced people, ‘you have to go this way or you have to go that way,’” he said of the mass protest. “It just spontaneously happened that way. People weren’t afraid.”

Taken Out of Tule Lake

“That whole thing started in February [1943],” recalled Tanimoto. “All of a sudden, one evening, they showed up.” Describing the scene, he said the WRA “came up and brought half a dozen Dodge trucks; called out our names. We were all ready; had our suitcases all packed, ready to go. They took us outside and then separated us into two groups.” Tanimoto recalled that, “The older people were sent to Alturas. They thought somebody in that group was the leader.”

“By the time we got to Klamath Falls, it was dark. It was a little after 5 o’clock,” remembered Tanimoto. “I thought we’d be in cells, but no, it was a long dormitory, no bars on the window. We were upstairs, in a two-story building. It was heated; it had steam heat. It was comfortable, being we were all together. It was heck of a lot easier than you being locked up in a cell all by yourself.”

“On about the third day, we started getting mail from camp, telling us, ‘You guys were brave to do that,’ and they started sending us cookies and all that,” recalled Tanimoto.

Jail in Klamath Falls lasted only about one week. Tanimoto speculated that because none of the Block 42 protesters was charged with a crime, that they had to be removed from the County jail. The jail in Klamath Falls is in Klamath County in Southern Oregon, the jail in Alturas is in southeastern Modoc County.

“Guess they found out they couldn’t hold us there and they didn’t want to let us back in the camp. So they took us to the CCC camp,” Tanimoto recalled.

“When we got to CCC camp, the first night there, man, when they had the submachine gun out in front, we was kind of scared, you know? We thought they might line us up and kill us, but nothing happened,” he said. “From there on, we never even thought about being murdered. But, when we first got there it kind of scared us.”

The Block 42 protesters were held for a month, said Tanimoto.

“Most of our group was in one barrack. Then, a bunch of new guys took the other barrack,” he said, referring to another larger group of about 100 Tule Lake protesters who occupied a second barrack in the complex of buildings at the CCC camp.

While at the CCC camp, Tanimoto described a group of Block 42 dissidents put to work at the Fish and Game headquarters digging a 200-foot trench and pouring the cement for their garage. “They were happy with the job we did for them,” said Tanimoto, so as a reward, they were taken to visit the caves and caverns in Lava Beds. “I understand Fish and Game caught hell for that,” he laughs.

They were never told why they were being held at the CCC camp.

“Nobody told or asked us anything. We were just in there,” said Tanimoto. “Find out later that was illegal, ‘cause we didn’t get charged with anything.”

“One month later they say, ‘you guys can go home,’” he remembers, and they returned to Tule Lake, back to Block 42. Life was pretty much the same as before, said Tanimoto, “but, if any trouble started, there would be sentries surrounding our block.”

On his return to Tule Lake, Tanimoto married his longtime sweetheart and in October 1945 returned to Gridley and resumed farming. In the late 1960s he pioneered the cultivation of kiwi fruit.

“I’d do it again,” Tanimoto said of his resistance to answering the loyalty questions.

“Guess I’m just hard headed,” he mused. “I’d be more hard headed next time because I know what the rules are on that,” referring to the fact they were never charged with a crime “We were protesting [because] we weren’t being treated like American citizens.”

NOTE:

Included as part of the Tule Lake Segregation Center National Monument, the Civilian Conservation Corps camp (CCC) known as Camp Tulelake, where the loyalty question protesters were imprisoned, is located near East-West Highway on Hill Road, approximately five miles from the segregation camp site. Following a month of use to imprison the Loyalty Question protesters, it was used again in October 1943 to house 234 Japanese Americans recruited from Topaz and Poston and used as strikebreakers in labor protests roiling Tule Lake after the mass reshuffling created by segregation. The strikebreakers earned $1 per hour, earning in two days the $16 a Tule Lake inmate earned in a month.

In May 1944, it was converted to a POW camp, briefly housing Italian POWs, and in June 1944 the CCC camp began filling with German POWs whose numbers reached 800 by October 1944. Ironically, the German POWs were free to ride their bicycles to the farms and around town; they shopped in stores and picnicked in the hills, wearing their shirts stenciled with P.O.W. on the back, while American citizens with Japanese faces were denied the same freedom.

* This article was originally published in the Nichibei Times on January 1, 2009.

© 2009 Barbara Takei