Last January, my uncle passed away. At 93 Gordon Kiyoshi Hirabayashi was an acclaimed civil rights hero for his World War II resistance to cur few and the camps, and for his life-long commitment as a Quaker to peace and global understanding. Unbeknownst to Gordon, over the past five years I have come to know him under rather unusual circumstances that I’d like to share with you here.

Gordon Kiyoshi Hirabayashi. Courtesy of Gordon Hirabayashi, Japanese American National Museum (97.296.1)

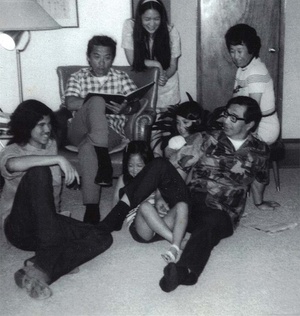

Since the ‘60s, Gordon and his family lived in Edmonton, Canada where he was a professor in the Sociology Department at the University of Alberta. Every summer until I was 18 we would drive from San Francisco to Seattle, and I’d have a chance to visit relatives on both sides of my family. Shungo, my grandfather, and Sadako, my step-grandmother, ran a nursing home during these years, and so their large, rambling business became our family gathering point where I first got to know my uncles, aunt, and cousins. At that point Gordon already seemed professorial to me. In the course of these visits, though, I learned about Hirabayashi family history, and Gordon’s 1943 Supreme Court case.

As the 1980s rolled around, his ‘43 case was reinforced in my mind as I saw numerous press clippings related to Gordon’s coram nobis appeal. Gordon, Fred Korematsu, and Minoru Yasui, who were each convicted for resisting mass incarceration during the war years, returned to court forty years later seeking redress. Each charged “government misconduct” in the specific for m of federal prosecutors who had intentionally concealed evidence that would have belied charges of disloyalty made against Japanese Americans in the 1940s.

Fast forward to 2005. My aunt Susan, Gordon’s wife, asked my father Jim to come up to Edmonton to help her sort through Gordon’s personal files. The plan was to determine which items should be given to the Japanese Canadian Museum. As Jim read and sorted, he realized that—although there were autobiographies by Gordon as well as numerous inter views and biographies—Gordon’s files contained primary sources from the ‘40s that no one had tapped before. Specifically, Jim identified a set of spiral notebooks that were essentially Gordon’s prison diaries. These were most heavily focused on Gordon’s initial confinement in Seattle’s King County Jail, but also included entries when Gordon was incarcerated in Arizona as well as at the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary in Washington. After shipping these materials back home to study, Jim determined that there was enough material to put together a full-length biography in Gordon’s own words.

In 2007, Jim invited me to work with him on this endeavor. I began to read Gordon’s letters and diary myself, and we started to talk about what format would be most effective for this manuscript. What seems so special now is the process that evolved as we worked. I read many different items that Gordon had written during the war. I also had many conversations with Jim, where I asked about Hirabayashi family history, names and places that I was not familiar with, and the overall context of the Pacific Northwest during the war years.

In 2010, we submitted our manuscript to the University of Washington Press which reviewed and accepted it for publication. At this juncture, looking back, I can say that I actually never knew the grown-up Gordon Hirabayashi very well. I never, for example, had a sustained conversation with Gordon about his coram nobis case. Now, in 2012, I can also say that over the past five years, I’ve co me to know the 24 to 26-year-old Gordon in some depth. This is unique in terms of how I’ve ever come to understand something about another person. With the publication of our co-authored book, Jim and I have done our best to share with others the twenty-something-year-old student, resister, pacifist, and humanitarian who we’ve come to know through his prison writings. As we come near to the end of this project I realize that it’s been a privilege to get to know Gordon in this fashion, even though it’s happened fairly late in my own life.

Photograph commemorating the efforts of the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR) to win redress through a class action suit against the government. 1987. Photograph taken by Doris Sato. Figures represented: Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi, Michi Weglyn, William Hohri, Aiko Herzig and Harry Y. Ueno. Gift of Hannah Tomiko Holmes, Japanese American National Museum (88.4.1b)

*This article was originally published in the Inspire, the Member magazine of the Japanese American National Museum (Spring 2012).

© 2012 Lane Hirabayashi