A modest portion of gohan and the smell of Kikkoman soy sauce, with its hexagonal logo, makes me recall my Nikkei origins. Bringing a morsel of Japanese food to my mouth is magical and transports me to those happier times I shared with my grandfather, Noboru Tachibana Kamada of Kagoshima; such memories also served as a reminder of how significant it was for me to be the granddaughter of a Japanese in Chile, an unusual situation in my country because Nippon immigration is rare.

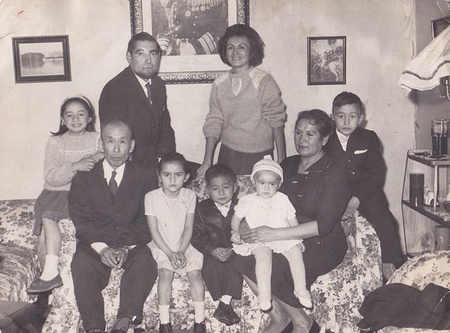

My grandfather's family in Japan (he is the one with his hat in hand). The photograph is my personal property.

I can see him in his home at 1742 Blanco Street, married to my grandmother Auristela Valenzuela Yevenes. His house had big windows with a view of the ocean, and it became the meeting place for many Japanese who passed through the port of Valparaíso, here in Chile, and that for me—my grandfather—was the only link to Japanese culture.

I believe that I was happiest when he spoke in his native tongue. My grandmother did her best to make my grandfather feel comfortable in this country; one of things that she would do was to cook Japanese food in the way my grandfather had taught her.

But how do you go about cooking Japanese when finding the necessary ingredients is so difficult? Of course, in today’s globalized world, it is easy to find ingredients to prepare Japanese-style meals. In the first half of the twentieth century, however, it was a sign of status if you had some imported item in your kitchen, or if you had a family member in the armed forces who brought back things from other corners of the world. You can imagine how difficult it was, therefore, to prepare Japanese meals without having those very ingredients that give Japanese cuisine its identity.

The fact that my grandfather had lived in Valparaíso was part of the special magic that allowed him to obtain those ingredients with greater ease. Valparaíso is a port city that experienced globalization earlier than other parts of the country in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; this historical reality was a major reason why the port city was designated as a “Patrimony of Humanity.”

The house was situated in front of the Pacific Ocean, and my grandfather had a chair in front of the window that allowed him to see the hustle and bustle of the port. He always seemed to be waiting for a Japanese ship to arrive, and often a ship with a white “K” against a red backdrop on the ship’s smokestack (signifying the Kawasaki Line) would come to dock. When this happened, my grandfather sprinted to the port. Soon he would return home with both Japanese sailors and several food items to cook. I’ll never forget the bottles of soy sauce, sake, nori, katsuobushi, mirin, ocha, miso, flower-shaped products, and rice noodles.

His brothers in Japan would send him gifts and ingredients by boat. I recall the two-liter bottles of soy sauce that my grandmother hid behind the dining room door as if they were part of some stolen treasure. There also was a shelf where my grandfather would store the gifts; the smell of the place still brings back memories.

During my childhood, I was fortunate enough to live for some time with my grandparents because I learned so much from them about Japanese history and traditions. Sitting down with them at mealtime was—without doubt—one of the most memorable traditions.

One of the meals that I enjoyed so much was kamaboko. My grandmother would get some very fresh hake, fillet it, and put it in a suribachi. With a spatula or wooden stick, she would press those pieces of fish through the walls of a strainer, which had several little sharp blades that would turn the fish pieces into a soft paste. Afterwards my grandmother would remove any bad or hanging parts, add cornstarch and eggs, and with her hands she would make it into a kind of patty that was 12 centimeters in diameter, which she would then subsequently fry. After frying she would cut the fish patties into fine slices that were served with gohan. Everyone in the family learned to eat with ohashi. I remember when my grandfather taught me how to start eating them in the middle; starting in the upper part would bring bad luck, while the lower part poverty.

Another memory of mine related to Japanese cuisine is when we would get together and consume sukiyaki, which generally took place at the end of the year. They would cut up the vegetables and the meat, placing a special pan on the stove that my grandmother had asked to be made just for this dish. My grandfather sauteed the onions and meat, adding the vegetables, soy sauce, and mirin. As she was cooking, she would place the finished part of the dish to one side of the pan, while adding new ingredients.

The entire family would sit around the stove and each of us would have a cup of gohan and take what we wanted to eat from the pan. When the food was almost gone, my grandfather would add a flower-shaped ingredient that was moistened with juice squeezed out of the ingredients, adding harusame, or transparent noodles. For me and my siblings, these were the tastiest noodles ever (the noodles were not found throughout Chile during that time). Sake also was placed on the table within a pot of softly boiling water; we would drink the sake in small glasses. My nostalgic grandfather would soon begin to sing Japanese songs, usually with his eyes closed. The sukiyaki was a family party.

Family get-togethers also provided the opportunity to eat Japanese food, and there was alway onigiri, or rice balls filled with katsuobushi and umeboshi (just thinking of these dishes makes my mouth water). They made gohan, whereby you soak your hands in water and salt, and in the palm of your hand you shape them. In the middle you put the katsuobushi or umeboshi shavings. You finish up by shaping them into rice balls.

After my grandfather’s death in 1973, it was difficult to savor Japanese food again. Nevertheless, we maintained the tradition of eating gohan, soy sauce, and on a few occasions we also made sukiyaki. After many years, however, we reunited at the Nikkei Corporation; it was an opportunity to savor once again the flavors of Japan, flavors that we had never really forgotten because they remain part of our culture, as well as that of the Japanese immigrants who come to Chile, leaving a multicultural legacy to our society.

© 2012 Katrina Sanguinetti Tachibana