Where are you from? Where did you learn to speak English? Do you eat regular food? American?

For most of my life I have lived in communities where there are few Asians, let alone any Sanseis. Years ago classmates, strangers, would ask the inevitable questions. To them being Japanese-American meant being Japanese.

Later, with the rise in popularity of Japanese culture and cuisine, the interactions changed a bit. Instead of being interviewed, I became an audience for my coworkers’ reviews of the latest restaurant or cultural trend or historical event. Anything Japanese.

Sometimes they didn’t look directly at me, but positioned themselves to see me in peripheral as if they were on stage addressing a class, and I was watching from the wings. This time the questions and comments were more rhetorical. I would adopt a closed lipped tight little smile, a slight dip of my head. I would partially turn away feigning a shy, subtle recognition of what I hoped they would think was our profound shared insight. “Oh yes.” “Of course.” “Mmm.”

It occurs to me that when I was a child I tried to convince my classmates that I was just like them. I didn’t want them to think there was anything different about my house, my family. But later, as a young adult, I tried to imply just the opposite. My family and I were exotic. In truth I don’t know anything about their version of being Japanese-American.

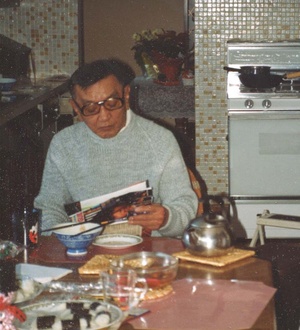

I spoke only English growing up. I didn’t practice ikebana or karate or even origami (the denial sounds silly today). My father was not thin and frail, and he didn’t speak in riddles or use metaphors like the Asian archtypes (stereotypes) on TV. He was gruff and bristly and abrasive. He set the tone for our family meals which were not quiet or refined. In our conversation we weren’t humble or modest. It was in-your-face dialogue about the working man and the system he was up against.

And what did I really eat? My mother scoffed at gourmets. “Who can’t cook when you buy all those expensive ingredients? The real cook uses what she has.” Scrambled eggs with onion served with okayu (we called it okai). Meatloaf or fried chicken or skirt steak smothered with canned tomatoes from her garden. Pork chops and sauerkraut served over rice. Rice. Always rice. And tea.

On the hottest summer days there were cold noodles; we ate in the basement with a Westinghouse fan blowing at our ankles. Cold noodles I’ve seen offered in Japanese restaurants. But the noodles never seem as fat, the broth never as flavorful.

The same is true for her giant rolls of sushi and overstuffed inari (“Turtles,” we called them. Fat turtles. I only learned their Japanese name a few years ago). “It’s country food,” my father said. “Your mother’s a farmer.”

I don’t have any recipes to share; I wish I did. But it occurs to me, like in so many families, it was not just about the food. My childhood experience was not unique. Because we were the only ones we were tormented and bullied and ostracized.

I read that in families dealing with abuse, the members pretend to the outside world that there is nothing out of the ordinary about their family, their household. With my family we did it in reverse. Once inside our home, safe around our dinner table, we acted as if our outside experiences were just the same as what we saw on TV and in magazines. We debated and talked about issues and ideas as though we were full-fledged members of the community. And over the tea and rice and country food we had done, I now realize, what my mother admired in other cooks. We had made a meal from what we had. We were Japanese-Americans. Authentic.

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee Selected this article as one of their favorite Itadakimasu! stories. Here are the comments.

Comment from Nina Kahori Fallenbaum:

This piece’s vivid evocations of homestyle country cooking, as well as loving depictions of parents and family life, will resonate with Nikkei all over the globe. Much complexity is captured in just a few words: the challenges and unity formed by growing up among few other Nikkei, and the happy memory of inarizushi “turtles” made by her mother. “The real cook uses what she has,” says Nishimoto’s mother, evoking a proud tradition of seasonality, flexibility and thrift that endures across the Japanese diaspora. Despite hardships, the love and care expressed through food in the Nishimoto family will resonate across cultures and circumstances.

Comment from Nancy Matsumoto:

I like the feistiness and honesty of Barbara Nishimoto’s Authentic, and the defiant pride she takes in the way her family doesn’t conform to Asian stereotypes. Her descriptions of the simple “country” dishes her Nisei mother made remind me of dishes my mother and grandmother made—many of them were the same. The way she connects those meals to an authentic, self-created Japanese American identity is both moving and powerful. Although I didn’t grow up feeling as isolated and ostracized, this essay made me feel the author’s pain in a deep way, and it brought back my own childhood sense of the family dinner table as a magic circle where the slights and wounds of the outside world had no place.

© 2012 Barbara Nishimoto