Read Part 23 >>

THE RIGHT OF NATURALIZATION

The greatest legal barrier barring the Issei from equal participation in the United States was their classification as “Aliens Ineligible to Citizenship.” One of the earliest Issei to fight for naturalization was Namyo Bessho, who enlisted in the United States Navy in 1898. Bessho was a veteran of two wars (the Spanish American and World War I) and acted as personal steward for presidents William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Taft.

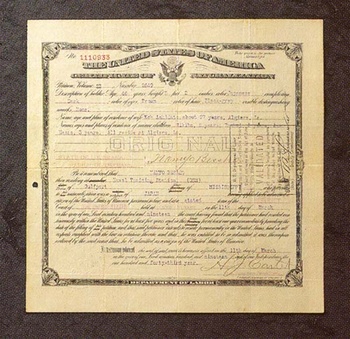

In 1910, Manyo Bessho filed a petition for naturalization under the Act of July 26, 1894 which granted citizenship to “any alien” over 21 years of age who served five consecutive years in the Navy or Marine Corps. His petition was rejected by Justice Nathan Goff, who argued that Congress had clearly intended to exclude all persons of the Mongolian race from the privilege of becoming naturalized citizens.

During World War I, Bessho was one among 838 Japanese who served in the United States Army. When the war ended, Bessho petitioned again for citizenship. On March 11, 1919 he was granted naturalization under the law of 1918 which provided that “any alien” serving in either the Army or Navy during the war was eligible for citizenship. However, Bessho’s victory was short-lived. In 1925, the United States Supreme Court ruled in the Toyota case that Japanese veterans of Word War I could not become naturalized citizens. Finally, on June 24, 1935 a measure signed by Franklin Roosevelt granted Asian veterans citizenship rights. Namyo Bessho was a citizen at last.

Certificate of naturalization of Namyo Bessho. (Gift of Indiana Bessho, Japanese American National Museum [92.81.16])

TAKAO OZAWA V. UNITED STATES

After the passage of Alien Land Law, naturalization became a matter of economic survival. Both the 1913 and 1920 Alien Land Laws of California had avoided direct reference to Japanese but used the phrase “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” Earlier naturalization statutes had granted eligibility of American citizenship to only persons of white or African descent. The Japanese community agreed that “the basic solution” to the discriminatory laws was the acquisition of naturalization.

After considering their options, immigrant leaders decided that litigation would be the best way to obtaining naturalization since it did not depend on American public opinion or diplomatic initiative. The search for an ideal test case finally ended with Tadao Ozawa. Ozawa, who boasted in his legal brief that “I do not have any connection with any Japanese churches or schools, or any Japanese organization here or elsewhere,”1 unwittingly became the representative for all Japanese immigrants in his battle to become an American citizens

Ozawa seemed to be a perfect candidate. He graduated from high school in Berkeley, California, believed in the Christian faith, married and American educated woman, sent his children to American schools, spoke English at home, and worked for an American company. Arguing on his own behalf he wrote: I neither drink liquor of any kind, nor smoke, nor play cards, nor gamble, nor associate with any improper persons. My honesty and my industriousness are well known among my Japanese and American acquaintances and friends; and I am always trying my best to conduct myself according to the Golden Rule.2

Ozawa fulfilled all the legal requirements set by the Act of 1906, which required applicants to file a petition of their intent to naturalize at least two years before their application. Ozawa filed his petition of intent in 1902 and formal application in 1914. As resident of the United States and Hawaii for more than twenty-eight years, he satisfied the five year continuous residency requirement.

After facing a series of rejections at the lower court levels, his case was referred to the Supreme Court on May 31, 1917. Some Issei leaders favored postponing the case because of unfavorable public opinion that lessened the chances of victory. Members of the Japanese community and the Japanese Foreign Ministry personally appealed to Ozawa to withdraw his case, but Ozawa was determined to continue his battle, even in the “face of death.”3

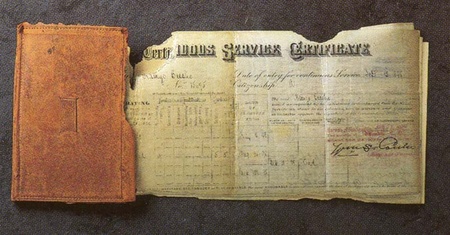

Ship's log of Namyo Bessho, 1889-1920. (Gift of Indiana Bessho, Japanese American National Museum [92.81.13])

Notes:

1. Ibid, p. 219.

2. Takao Ozawa, “Naturalization of a Japanese Subject,” undated brief, JARP, JFMAD, reel 39, in Yuji Ichioka, The Issei, p. 219.

3. Shin Sekai, May 7, 1918, in Yuji Ichioka, The Issei, p. 223.

* Issei Pioneers: Hawai‘i and the Mainland, 1885-1924 is the catalogue accompanying the National Museum’s inaugural exhibition. Using artifacts from the National Museum’s collection to tell the story of the courageous “Issei Pioneers,” the catalogue focuses on the early immigration and settlement years. To order the catalogue >>

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum