Read Part 2 >>

During the Edo Period (1603-1868), there was a great flowering of ghost stories in many areas ranging from art to entertainment. Reider (2000) explains the psychology of the Edo people: because travel abroad was forbidden, there was a heightened perception of foreign lands, particularly China, as exotic places where mysterious things were believed to happen (p. 278). The parents of the issei grew up in late Edo culture and passed its longing for the cultural other to their children who later came to Hawaii.]

According to Ogawa (1978), the first 150 Japanese arrived to Hawaii in 1868, right after the end of the Edo Period, to work on the plantations and almost 100 chose to remain. Thirty years later Japanese made up the largest single ethnic group in the Island. This large minority population gradually integrated with other peoples in work and marriage on the islands and their inner life influenced Hawaiian culture broadly. In Obake Files, Grant (1996) says that the early Japanese in Hawaii “brought their ghosts that commingled and ‘intermarried’ with indigenous Hawaiian spirits and those of other races” (p. 17). It is not clear exactly what Grant means by the term ‘intermarry,’ but Japanese expressions of the supernatural could be heard in many homes on the island, not just Japanese ones.

An important element of this cultural diffusion in Hawaii was the teaching of Buddhism about different types of spirits and supernatural beings that inhabited the life after death. There were hungry ghosts (gaki), for example, who fed on leftover scraps of food. These spirits were always hungry, symbolized by their needle-thin necks and flaming red hair (a sign of protein deficiency). Ogawa (1978) writes that Buddhism was encouraged by plantation owners for self-promoting the community. He sees a role played by the plantation work community in “a network of perceptions dealing with the supernatural” (p.55).

Not only religious teachings from Buddhism but also folklore was part of every Japanese household that would spread widely as intermarriage with Hawaiian culture, which would have taken place. Nature-spirits (like the imaginary water creature called kappa) and communications with the dead were an important part of many issei experiences that were adopted widely by other Hawaiians (Ogawa, 1978). For example, the Japanese bon festival for welcoming the spirits of dead ancestors back into the home has become a prominent part of every community.

After Japanese immigrants settled, they might have followed their parents in telling their children about the existence of certain monsters who threatened those who would not obey the rules. Grant (1994) also introduces another folklore belief in immigrant culture in Hawaii, kappa.1 In Japan, kappa is a monster or an imagined troublesome creature and the belief widely distributed. The broad distribution of this creature is evidence due to the wider range of its name. Some examples are: gawappa in Kumamoto; garappa in Kagoshima; and gongo in Okayama, where immigrants came (Chiba, 1988).2 After Japanese immigrants settled, they might have started to tell children that the existence of monster to control or protect children drown in pond by telling them that kappa would drag children into pond and kill them (Grant, 1983).

The function of monster tales was so relevant in Japan. A Japanese ethnographer Kunio Yanagita (1939) describes a typical way of such a story could be used to control children in rural areas. The Japanese parents tried to prohibit their children play in hide-and-seek in evenings so they created some monsters to scare them. When children said “why?” some parents created some strange-instant names. When children refused to come home at night their parents would warn them, “ato no-ko ha mujina no-ko” (that late children must be mujina’s child” (an old saying from the island of Sado, Niigata prefecture)3 (Yanagita, 1939, p.22). According to Yanagita (1939), in order to make children hurry to their homes from the playground and not stop to talk with strangers, parents told them to beware of becoming children of mujina. The phrase, “ato no-ko ha mujina no-ko” is sentimental for me because it evokes my childhood memories. When I was still a child, about the 2nd or 3rd grade, neighborhood children and I chanted a phrase, “karasu-ga naku kara kaero (let’s go home because crows sing),” to each other in order to urge ourselves to go homes before dark. This self-regulating system in children in play might have existed in Hawaii too.

The contemporary Hawaiian mujina is a hybrid ghost created by the Asian and Hawaiian cultural encounter. It is a mixture of many ghosts and folklore stories in addition to some mysterious elements from both Japan and Hawaii, and maybe from other countries as well. Many influences migrated from the distant past in the collective memories of the Japanese and, maybe, other Asian inhabitants of the islands. They crystallized in eyewitness accounts of a faceless female with beautiful hair who is not unlike Madame Pele. These females have the same sort of power to allure and scare men. The broad images of Pele would have welcomed the spiritual female from Japan. Glen Grant is right, therefore, to name this phenomenon “intermarriage” of ghosts, but he is not right to focus so much attention on her similarity to Hearn’s mujina.

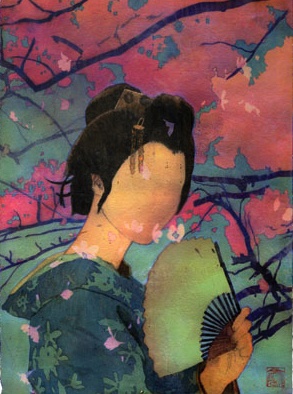

Painting by Edwin Ushiro “Cut Like When Asakusa Recovered Mujina.” In “Painting a Nightmare” by Wagner, K.D. Honolulu Magazine, October 2008.

Despite the unknown origins of this particular ghost story in Honolulu, it is probably the flowering of kwaidan (ghost storytelling) in the Edo Period that provides the most fertile background for explaining the modern Hawaiian tale. The cultural practice, kwaidan, was brought to Hawaii by immigrants from Japan, maintained under Buddhist sponsorship, and spread widely through horror movies to the general populace. In other words, the story developed in the cross-cultural stream of Hawaii as a form of longing. One stream of this longing was of the Japanese in the Edo Period toward the world outside their grasp; another was of the Japanese immigrants’ in Hawaii who were homesick for their own culture in the homeland, but also willing to adopt another one based on female mysteriousness power. I assume that this blending of cultures in history in Hawaii is at the real root of the emergence of mujina in Honolulu.

A few days later I encountered Gary on a bus again. He told me that one day he saw a white male on one of the escalators at Sears in Ala Moana, coming in a hurry behind from him. He turned his body to give him a space to let him go. But next moment when he turned his face back, there was nobody. He still remembers what he wore and his specific face features. I asked him whether he saw a ghost. He was not sure since he had not checked if the man had feet or not. Then, I added a question whether it is common to believe that ghosts have no feet in Hawaii. His reply did not include any emotional hesitation, “I don’t know. That’s what my mother told me.” (personal communication, December 10, 2007).

Notes:

1. Grant (1983) describes kappa: "The kappa was an ugly, amphibious creatures about the size of a small boy of three or four years of age. The creatures’ s skin was a scaly greenish-yellow, its seaweed-like hair green and stringy." (p. 8A).

2. Mikio Chiba (1988) complied various names of kappa and other creatures throughout the nation in his dictionary of monster words.

3. On Sado, there is a famous raccoon dog legend called Don-saburou-tanuki that lent money to people (Sasama, 1994). The story also has a mujina version.

References

Aston, W.G. (trans). (1956). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London : George Allen & Unwin.

Chiba, M. (Ed.) (1988). Zenkoku yōkai-go jiten (The dictionary of national monster words). In Tanigawa, K. (Ed.), Yōkai: Nihon minzoku bunkashiryō shusei (Monsters: Japanese ethnographic cultural materials) (8), (pp. 393-517), Tokyo, Sanichi Shobō.

Ema, T. (1977)[Originally published in 1923]. Nihon yōkai henka-shi (The historical changes of Japanese monsters). In Ema Tsutomu chosaku-shu (Collections of Tsutomu Ema)(6), (pp. 367- 452). Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha.

Grant, G. (1996).

-A faceless woman update. In Obake files. (pp.126-129).

-A woman in the rain. In Obake files. (pp. 58-59).

-The hitchhiker lights a cigarette at Sandy beach. In Obake files. (pp. 60-64).

Honolulu: Mutual Publishing.

Grant, G. (1994). Ghosts of a plantation camp: thousand of things sinister and dark. In Obake: Ghost stories in Hawaii (pp. 13-21). Honolulu: Mutual Publishing.

Grant, G. (1983). In search of kappa and mujina: Japanes obake in Hawaii, The Hawaiian Herald, October 21, (4), 20. (pp. 1A, 8A, 8B).

Hearn, L. (1971)[Originally published in 1907]. Mujina. In Kwaidan: Stories and studies of strange things (pp. 75-80). Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc.

Komamiya, S. (1993). Mujina ka tanuki ka (badgar or raccoon dog?). Newsletter (20) 1993, March. Saitamaken-ritsu shizenshi hakubutukan (The Saitama Natural History Museum). Retrieved from: http://www.kumagaya.or.jp/~sizensi/print/dayori/20/20_6.html

Lin, S. (1994). Dagou sou shen ji (Searching for gods). Minguo 83. Takeuchi, A. (trans).

Nagano, S. (trans). (1967). Konjaku monogatari (Konjaku tales). Tokyo: Kōdansha.

Ogawa, M, D. (1978). Their great thirst. In Kodomo no tame ni (for the sake of the children): The Japanese American Experience in Hawaii, (pp. 43-58).

Reider, N, T. (2000). The appeal of kaidan: Tales of the strange, Asian Folklore Studies, 59, 265-283.

Sasama, R. (1994). Kanekashi tanuki. In Zusetsu nihon mikakunin seibutsu jiten (Dictionary of unidentified mysterious animals with pictures) (pp. 119-120). Tokyo: Kashiwashobō, Ltd.

Yanagita, K. (1956) [Originally published in 1936] Yōkai dangi (A lecture about monsters). In Yōkai dangi, (pp. 13-38). Tokyo: Shūdō-sha.

© 2011 Kaori Akiyama