While not exclusively the case, we can simply surmise that fascinating individuals with fascinating life events make fascinating history.

To appropriate Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s famous phrase, well-behaved Japanese Americans seldom make history. From Fred Korematsu to Toyo Miyatake to Yuri Kochiyama, the Japanese Americans whose lives are memorialized in our exhibitions are primarily those who went against the grain and followed their beliefs.

Although the vast heterogeneity and hybridity of Japanese Americans across three different centuries makes it difficult to find the universal common threads of Japanese American identity, the ideas of resistance and struggling for justice are uniting points that make a historical museum like the Japanese American National Museum so interesting.

While most of us know that Japanese laborers started immigrating to the United States during the end of the nineteenth century, did you know that there was a Japanese American in the U.S. Navy during the Spanish-American War?

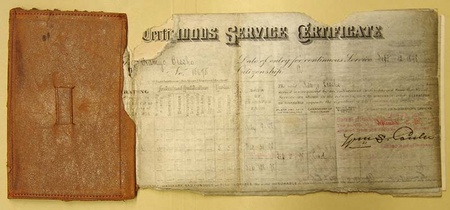

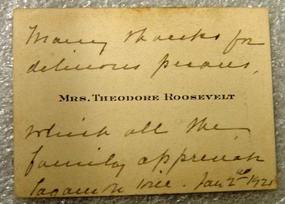

Namyo Bessho was born in Japan in 1872 and immigrated to the United States during the 1890s. While most other Japanese in the United States were finding jobs as immigrant laborers in the agricultural or domestic industries, Bessho instead joined the Navy on July 9, 1898, and would serve as a cabin steward until 1921. He kept excellent records of his travels with the Navy, complete with fingerprints and health reports. He even served the Taft and Roosevelt families while aboard at sea.

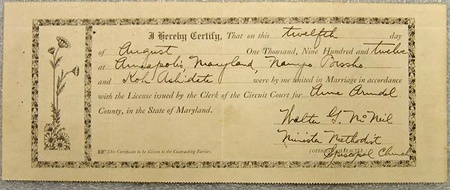

Sometime in 1901, Bessho met Koh Ashidate at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, while she was performing with a Japanese dance troupe. From what we know, Koh Ashidate was married to Mr. Rikumatsue Ashidate, and she gave birth to her daughter Rikiko Indiana Ashidate in 1908 (her middle name coming from the state where she was born). At the turn of the century and in an era of immigrant bachelor societies and arranged marriages, one can only wonder the circumstances of Namyo Bessho first meeting a married woman, and later marrying her and adopting her daughter in 1912. Understandably, these are the types of specifics that have since gone to the grave.

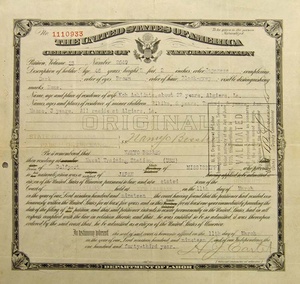

According to the “grand narrative” of Japanese American history, Isseis were unable to gain U.S. citizenship due to several racist laws and verdicts such as Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922). Nisei children could be American citizens by birth, but it was not until after the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 that Isseis could do likewise. However, Bessho actually was able to naturalize as a U.S. citizen in 1919, after a nine-year petition and legal battle. Sadly—although not surprisingly, considering the times—his American citizenship was later taken away and was not reinstated until 1935. Here is a picture of Namyo Bessho’s original certificate of naturalization from 1919 and a photograph of Koh Bessho when she finally naturalized in 1953.

In the larger scheme of Japanese American history, Namyo Bessho’s story is relatively insignificant. His actions did not directly lead to any national legislation, nor was his occupation as a ship steward particularly noteworthy. Yet this should not diminish the importance of knowing that he was one of the first Japanese immigrants to naturalize as an American citizen. It also should be mentioned that these pieces in our collection are especially valuable due to the overall dearth of Issei materials. Through Namyo Bessho, we can begin to see one of earliest examples of a Japanese individual blazing a new trail and dedicating his life to the welfare of his adoptive nation, regardless of whether or not his adoptive nation would claim him as one of its own.

* This item was included in the recent JANM exhibition American Tapestry: 25 Stories from the Collection (http://www.discovernikkei.org/nikkeialbum/albums/434/slide/?page=1)

* For Japanese readers, here is a translated article on Bessho by Akemi Kikumura Yano: http://www.discovernikkei.org/journal/2011/6/13/issei-pioneers/

© 2011 Dean Adachi