It’s a mixture of emotions. Satisifying, to be sure. Surprising, too, because the presidential apology1 was unexpected. Some thought that it would never happen. At the same time some feel sad because it took so long to apologize that their own parents didn’t live long enough to witness it.

Crystal City was part of their childhood, leaving a indelible mark for the rest of their lives. Almost seventy years ago they had their freedom taken from them; they were taken from Peru and sent to the United States as if they were merchandise to be sold abroad rather than human beings.

The Peruvian government deported 1,771 Japanese families to the United States during World War II. When the war finally ended, the vast majority either went to Japan or stayed in the United States. Very few were able to return to Peru. Among them, however, were two sisters, Yuriko and Miyoko Mishima, and another group of siblings: Humberto, Teresa, and Carmen Tochio Villanueva.

SIMILAR DESTINIES

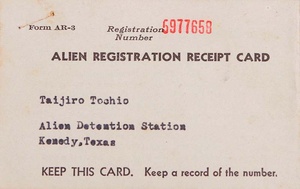

The Tochio Villanueva family operated a bazaar on Mercaderes Street in the city of Arequipa, located in southern Peru, when the Peruvian government initiated deportation proceedings against the Japanese community. The father was the first to be deported in late 1942. An indignant Teresa says in loud voice, “How is possible to separate an innocent man, a father, from his children? They did this to many families.”

When the United States announced that those who had been deported could return to their families, the mother decided to leave the family business in the hands of her sister. She left with her three children (Humberto, Teresa, and Mary; Carmen was born afterward) for Callao, where in 1943 they left for the concentration camp located in Crystal City, Texas.

The Mishima sisters sailed on the same boat as their parents. It was on that voyage that their destinies became intertwined.

“When we were headed for the Panama Canal, they told us that they were not allowed to mingle as a group, that a bomb could fall on us. They then gave us lifevests. My mom received four of them, one for each of her kids,” Teresa tells us.

Her mother had to take care of her little ones, however; her hands were always full. At that time a higher power seemed to appear from nowhere. "Miyo-chan and Yuri-chan (Miyoko and Yuriko Mishima) were with their mother when a voice cried out, "Ma’am, I’ll hold your baby for you." The person behind the voice took me in her ams. The memory comes from the mother, but now it’s hers too.

The Mishima family owned three stores and lived in San Isidro (Lima). They lost it all during the war, except for their house. The family also was a victim of looting that took place in May of 1940.

Yuriko and Miyoko Mishima were eleven and nine years old, respectively, when they were deported. The Tochio Villanueva children were a little younger: Humberto was six years old, while Teresa was only eight months old. Carmen was later born in Crystal City.

LIFE IN CRSYTAL CITY

The kids were too young to fully understand the horrors of war. Crystal City was their home. They studied and played there; their lives were not so different from other kids. They understood that their freedom was limited; the town was cordoned off, but they had sufficient space to move around and to have a normal life. Now that they are much older, they can better understand the horrors of war.

No one recalls suffering or having witnessed mistreatment at the hands of American soldiers. “The Americans treated us well; they showed lots of respect to our women,” says Yuriko.

There was one incident, however, that Humberto’s, Teresa’s, and Carmen’s father told them about. It happened when the deportees were alone in the camp. Desperate to be with his family, a Japanese began to run and hide. When the American soldiers were about to shoot him, Tochio-san shouted “crazy” several times so that the soldiers would know that he had lost his mind. The Americans lowered their weapons and detained him rather than shooting him. Tochio-san had saved his life.

The basic necessities were covered in Crystal City. “Everyday we opened the door and had two bottles of milk,” recalls Teresa. “We had a refrigerator and a kitchen, supplies, food, clothes, and an education,” Yuriko comments.

“We were free inside the camp; the Americans didn’t interfere,” she adds. The little ones received instruction in both Japanese and English. Parents didn’t have to work but did so only to keep themselves busy. They received a wage of forty cents an hour each day.

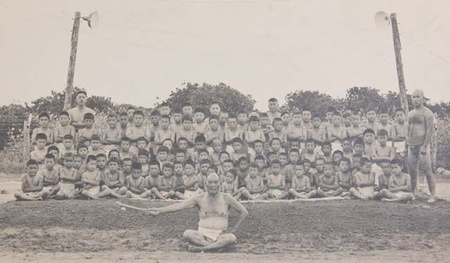

There was a school, hospital, hair salon, market, and laundrymat. They consumed miso2 and shoyu3 from Hawaii. They participated in sports and other recreational activities such as baseball, sumo wrestling, swimming, kendo, tennis, basketball, ikebana, baking, etc. They celebrated undokai4, heard speeches, went to concerts—especially Japanese and classical music--comedy theater, and Hawaiian and Huayno dance shows.

The camp also had Germans, Italians, and Japanese-Americans, but each group lived separate from one another. “We lived an independent life,” affirms Teresa. However, they recall the manner in which the Issei in North America offered advice: “You have to behave well, remain united, and nothing bad will happen.”

Each family had a house. Japanese-Americans had the largest of the homes, with their own bathrooms. The Japanese from Peru, however, had to share a bathroom.

Yuriko forged solid friendships in Crystal City. “I have nice memories. We were still young back then. We studied and afterward we would go to the pool or the library, but always together. We were like a family. We didn’t lack for anything; it was a good time for us,” she recalls.

“They treated us well in the camp, which is why I probably don’t harbor any bad feelings,” Teresa adds.

Life in Crystal City was tolerable because the families remained united. They weren’t free, but they had each other. Love sustained them.

Notes:

1. On 14 June 2011 President Alan García apologized to Peru’s Nikkei community on behalf of the entire nation for the deportation of thousands of Japanese and their descendants to the United States during the Second World War.

2. Pasta made of soy

3. Soy sauce

4. Sports festival

* This article was made possible thanks to an agreement between the Japanese-Peruvian Association (JPA) and the Discover Nikkei Project. It originally appeared in the journal Kaikan, 58 (July 2011), and republished on Discover Nikkei.

© 2011 Asociación Peruano Japonesa; © 2011 Fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa / Álvaro Uematsu