1. JOURNEY TO HAWAII

There was great excitement aboard the steamship City of Tokio as dawn broke on Sunday, February 8, 1885. Land had been sighted at last. Chika Saka and her husband Shohichi awakened their sons, Eizo and Yoshitaro. The family hurried on deck to watch the lush green mountains surrounding Honolulu harbor take form on the horizon as the ship approached its destination.

Almost two weeks had passed since the weary travelers had left Japan. In Yokohama, Shohichi Saka and his wife Chika had signed three-year contracts to work on the sugar plantations of Hawaii. Shohichi and other men on the ship had been guaranteed a monthly wage of $9 ($6 for women), $6 food allowance ($4 for women and $1 for children), free lodging, medical care, and steerage to Hawaii.

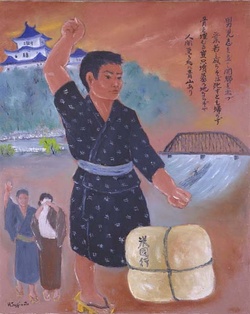

"Going to America" by Henry Sugimoto 1980. Henry Sugimoto Collection, Japanese American National Museum (92.97.105)

Also on board the City of Tokio was Robert Walker Irwin, the Hawaiian Consul who had negotiated the labor recruitment between the Japanese and Hawaiian government. As the official labor recruiter in Japan, he had an enormous stake in the success of the immigration project. He was paid $5 commission for every adult male immigrant. With 682 men aboard the City of Tokio, Irwin had already made a profit of $3,410. Over the next nine years of government sponsored immigration, he would be responsible for recruiting over 28,000 immigrants.1

Undoubtedly, Irwin was mindful of the critics in Japan who objected to Japanese working abroad as contract laborers. He knew about the fate of an earlier shipload of Japanese laborers who had come to Hawaii in1868. They were known as the gannen-mono (the “first-year” people), a motley group of 154 men and women, among them a saddlemaker, woodcutter, ceramic maker, samurai, and others, who were ill prepared to cope with the harshness of plantation work. Their dissatisfaction and complaints of mistreatment soon led to an investigation by the Japanese government and an end to further labor emigration to Hawaii.2

To avoid a similar fate as the gannen-mono, Irwin relied on the advice of his close friend, Kaoru Inoue, Japan’s foreign minister and Takasu Masuda, head of Mitsui Trading Company, who advised him to go to Yamaguchi prefecture, where the people were “not timid or afraid to go to far away places.” and to Hiroshima prefecture because the citizens were “sound and law abiding.” As a result, 68 percent (642) on board the City of Tokio came from these two prefectures. Future emigration continued to flow from these prefectures as well as from Kumamoto, Fukuoka, and Okinawa.

A “selective recruitment” was carried out in Japan with immigration of special character. The Japanese government was aware of the indignities experienced by the Chinese in the U.S. and was intent on convening a positive image to the West. The government stressed that “the right kind of people” emigrate to the U.S. knowing they would be the representatives of Japan.3

A Hawaiian Bureau of Immigration representative wrote the following to Charles Spencer, The Hawaiian Minister of the Interior in 1891: “The local authorities (in Japan) take upon themselves the care, that the permit to go to the Hawaiian Islands, is given only to men of good character, and those who are law abiding and industrious. The system is carried out with such scrupulous attention, that even among the great numbers who have come here…few turbulent men and no known violators of law and peace can be found.”4

The vast majority of immigrants were farmers. The Bureau of Immigration made it clear to Irwin that recruits “shall under no circumstances be taken from the inhabitants of towns or cities, or from among persons engaged or trained in pursuits other than agriculture.”5

Eighty percent of the recruits selected by Irwin were young men since he had received special instructions from Honolulu officials that women comprise no more than 25 percent of the total. The Saka family felt lucky to be among the 944 selected for voyage. Robert Irwin and the Japanese government had expected 600 applicants, but instead, over 28,000 had applied.

Takezo and Hisano Iida and their two children Shuntaro (six-years old) and Teruji (two-years old) were among the 76 families chosen. When the ship reached the shore, Hisano Iida breathed a sigh of relief. She was in the last month of pregnancy and experience told her that it wouldn’t be long before here third child arrived. As the others from the ship were directed to the Immigration Station for medical inspection, Hisano was whisked off to Queens Hospital where, the following day, she gave birth to a baby girl. When news of the infant reached Hawaiian King Kalakaua and his sister, Princess Lydia Kamakaeha Paki (later to become Queen Liliuokalani), the two visited the newborn at the hospital. The King was pleased. His dream of repopulating his kingdom with a “cognate race” was taking root.

Delighted with the auspicious birth of the Iida’s newborn, the King and the Princess decided to act as godfather and godmother at the baby’s christening. In honor of the Hawaiian Princess, the Iidas named their newborn Lydia. The King felt that the Japanese could “readily assimilate” into the Hawaiian economy and provide the large workforce needed for the sugar industry. Disease brought by European and American foreigners had reduced King Kalakaua’s native population from half million, and possibly more, to less than sixty thousand in 1866.

“Our national glory is on the wane,” the King lamented to Emperor Meiji. “The number of Westerners in our nation has increased to such an extent that their influence is now overwhelming….I fear that our days of independence are numbered."6 Eight years later his monarchy would be overthrown and all areas of the Hawaiian economy would soon be under the control of American and English settlers.

To stave off his fears, the King suggested a Federation of Asian nations, headed by the Emperor, that would hold the powerful nations of Europe and America in check. To cement the relationship, he proposed the marriage of his six-year-old niece, Princess Kaiulani, to the fifteen-year-old Japanese prince, Yamashina Sadamaro. After careful deliberation, Emperor Meiji politely refused the proposal.

In Hawaii, sugar planters were quickly becoming “king”. The Great Mahele (Division of Land) had paved the way for white planters to hold title to the land, extending the right of private land ownership to commoners and foreigners. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1870 eliminated the import taxes on Hawaiian sugar to the United States. And the increased population generated by the California Gold Rush and the disruption brought by the American Civil War (1861-1865) increased the demand for Hawaii’s sugar. Between 1870 and 1890, sugar production had skyrocketed from 9,000 tons to 300,000 tons. The only barrier that threatened its growth was the shortage of labor.

The Chinese were the first foreign workers imported to Hawaii in the 1850’s. As the number of Chinese grew and they left the plantations for better jobs, the Portuguese were recruited. Though the Portuguese initially allayed the planters’ fears of being too dependent on the Chinese, the importation of the Portuguese proved too expensive and the search for a large source of cheap labor continued.

Though most of the recruits came from Asia-China, Japan, Korea, and the Philippines- thousands immigrated from Puerto Rico, and several hundred more from Germany, Norway, and Russia. The planters deliberately maintained a mixture of nationalities in order to divide the workers, pit the groups against one another, and keep down the cost of labor. The Planters’ Monthly declared, “By employing different nationalities, there is less danger of collusion among laborers, and the employers…secure better discipline.”7

The Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser heralded the “first installment” of the Japanese migrants is “the most important event that has happened to Hawaii for many years.” Never having seen Japanese before, a surprised reporter marveled, “Most of them, the women especially, are actually white and they are clean.”

After they were released from the Immigration Depot, migrants were assigned to sugar plantations on five separate islands.”8 People from the same prefectures were sent to the same plantations. The Sakas went directly to Kauai, the Iidas were shipped to Hawaii, where six months later the Iida daughter Lydia died at the Kilauea plantation.

Complaints of brutal or unfair treatment immediately surfaced. One month after the Japanese arrived in Paia, Maui, they went on strike to protest the plantation’s refusal to punish a cruel Hawaiian co-tender. Japanese laborers struck in Papaikou, Hawaii when the plantation refused to pay overtime wages. The complaints were so numerous that a special commissioner, Katsunosuke Inouye, was dispatched to investigate.

Walter Murray Gibson, Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs, told Inouye, “the number and character of these complaints, coming as they do from a portion of about 720 Japanese people engaged in service here, exceed anything that the Hawaiian Government has had to deal with in the whole course of the immigration into, and employment to this country…”9 Gibson assured Inouye that his government was willing to comply to the “requirements of the Government of Japan.”

The numerous disputes foreshadowed the Great Japanese Strike of 1901. But most planters were overjoyed to see the arrival of Japanese laborers. Robert Irwin was elated too when he heard more positive reports from the planters and the Japanese laborers. On April 9, 1886 Irwin wrote to Foreign Minister Inouye.“The Japanese Emigration is an absolute success. The people are happy and well treated. All (or nearly all) work hard and are regular misers. The real character of the true Japanese farmer is hard working thrifty men. Nearly every Planter is entirely satisfied with Japanese laborers.”10

Notes:

1. Roland Kotanio, The Japanese in Hawaii: A Century of Struggle (Hawaii,1985), pp. 9-12.

2. Patsy Sumie Saiki, Japanese Women in Hawaii: The First 100 years (Hawaii, 1985), pp.17-26.

3. See Mitziko Sawada, “Culprits and Gentlemen: Meiji Japan’s Restriction of Emigrants to the United States, 1891-1909.” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 60. No. 3, August, 1991, (forthcoming) for greater discussion of Japan’s emigration policy to the U.S. and its effects on Japanese emigrants in the U.S.

4. Paul Neumann to Charles N. Spencer, Minister on the Interior, 18 March 1891, AH Bureau Misc, Files document 10, in Alan Moriyama, Imingaisha; Japanese Emigration Companies and Hawaii 1894-1908 (Honolulu1985), p. 18.

5. Lorrin A. Thurston, Minister of the Interior and President of the Bureau of Immigration, to Irwin, September 8, 1887, JFMAD 3.8.2.360, in Alan Moriyama, Imingaisha, p. 16.

6. James H. Okahata, A History of Japanese in Hawaii (Honolulu, 1971) p.76.

7. Planters Monthly, 2, No.11 (November, 1933); 177, 245-247, in Ronald Takaki, Pau Hana (Honolulu, 1983), p. 24.

8. There were 16 plantations on Hawaii, six each on Kauai and Maui, and one each on Lanai and Oahu.

9. Franklin Odo and Kazuko Sinoto, A Pictorial History of the Japanese in Hawaii 1885-1924 (Hawaii, 1985), p. 196.

10. Private letter from Irwin to Inoue, April 9, 1886, Japanese Foreign Ministry Archival Documents 3.8.2.9., in Alan Moriyama, Imingaisha, pp. 23-24.

* Issei Pioneers: Hawai‘i and the Mainland, 1885-1924 is the catalogue accompanying the National Museum’s inaugural exhibition. Using artifacts from the National Museum’s collection to tell the story of the courageous “Issei Pioneers,” the catalogue focuses on the early immigration and settlement years. To order the catalogue >>

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum