My grandfather, Yoshitaro Amano, was one of the more than two thousand Japanese Latin Americans seized abroad, shipped to the United States, and interned without charge during World War II. For a graduate research project on this topic, I read Seiichi Higashide’s memoir, Adios to Tears and watched Casey Peak’s documentary, Hidden Internment: The Art Shibayama Story, but there had to be more sources. After at least a semester-long search for additional first-person accounts, my mother casually announced that her father had written a book in 1943 about his experiences and asked, “Would that help?” It certainly would, though she could have mentioned this fact much sooner.

For the following narrative and excerpts from my grandfather’s memoir, I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my parents, Jean Hamako Amano Schneider and Harry Schneider, a U.S. Army veteran and Military Intelligence Service Language School linguist, who translated Waga Toraware No Ki (The Journal of My Incarceration) by Yoshitaro Amano into English. They worked many hours at their kitchen table, pen, paper, and a timeworn dictionary at hand, to make an obscure, sixty-year-old memoir accessible to those lacking fluency in Japanese.

Amano, captured in Panama on December 7, 1941, chronicled his experiences of capture, internment, and repatriation, offering his analysis of the war and his opinions on the differences between the Americans and the Japanese. Dr. Shiho Sakanishi, the first Area Specialist on Japan for the United States Library of Congress, wrote the foreword for Waga Toraware No Ki. Interned separately but repatriated on the same exchange boat as Amano, she persuaded Amano to write this book because, “the Japanese government appealed for the nation to engage in uplifting morale, challenging the intellect and in lifestyle innovation this year of 1943, the second year of World War II.”

Yoshitaro Amano was born in the thirty-first year of the Meiji Restoration, on July 2, 1898 in Ojika, Akita, Japan. He graduated from Akita Industrial High School’s division of mechanics, and attended Kurumae College of Industry, leaving shortly before graduation. Amano worked as a ship engineer, honing the entrepreneurial skills that would later finance his Latin American business ventures. After the Kanto earthquake of 1923 destroyed his family’s lumber business, Amano started a foundry, manufactured a pneumatic pump of his own invention, and formed a company to market the device.

Amano married Suzue Arai and had two daughters, Hamako and Ryoko. He also owned several successful pastry shops where he became acquainted with a wealthy customer, Chuzo Fujii, the owner of Suetomi Shokai Trading Company in Peru. Tokyo Imperial University professor Yoshiro Masuda, in an afterword written for the fourth edition of Amano’s memoir, surmised that this connection was a prime motivation for Amano’s overseas ventures. Personal reasons, perhaps not known by Masuda, may have been more significant.

In 1928, Amano’s wife deserted the family, leaving a toddler and infant behind. Newly divorced, Amano separated his daughters and left them in the care of family and friends in distant cities. Escaping either heartbreak or scandal, he traveled to Singapore, Mozambique, South Africa, Brazil, and Uruguay. Amano returned to Japan briefly upon the death of his father in 1928 and arranged for the construction of a massive mausoleum to hold his father’s remains before heading back to the Americas.

Passing through the Panama Canal to the Caribbean and Colombia, Amano was intent on settling in Venezuela until a request from his former business partner, Yoshi Ikawa, prompted yet another change in plans. Ikawa hired Amano to sell a shipload of merchandise intended for Peru but unloaded in Panama. Following a successful transaction, Amano stayed on to establish the Amano Trading Company, an import/export venture located in Panama City. He also helped organize the Ikawa Trading Company based in Japan expressly for the shipment of manufactured goods to Panama and Peru.

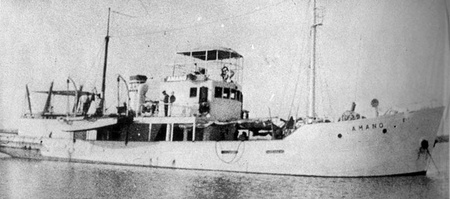

By 1930, Amano traveled regularly between Panama and Peru where he reestablished ties with his former customer, Chuzo Fujii. Soon, Amano solidified the business relationship by marrying Fujii’s daughter, Teresa Shizuko Fujii. Amano’s businesses flourished, and he built a small empire that included a ranch in Chile, lumber businesses in Bolivia, a quinine farm in Ecuador and two department stores called Casa Japonesa in Panama. He also established the Pacific Fishing Company based in Puente Arenas, Costa Rica and became a supplier to Van de Camp Company. His children, Hamako and Ryoko, came to Panama to christen his tuna clipper, the Amano Maru, commissioned from a shipbuilder in Shuzuoka Shimizu, Japan in 1933.

Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States had charged Panama with the task of arresting Japanese residents and interning them on Taboga Island, nine miles from the canal, where Panama had imprisoned German nationals during World War I. Panamanian authorities and American officials developed a list of potentially subversive aliens that included Yoshitaro Amano who wrote, “On America’s blacklist, I was at the top. Maybe just alphabetical, but Amano was at the top of the list.”

In 1941, The U.S. government banned trade with approximately 1,800 individuals and businesses on the Proclaimed List of Certain Blocked Nationals, compiled from a dozen Latin American countries that were suspected of providing aid to Axis countries. Amano’s name and that of his fishing company appeared on a Costa Rican list.

Amano’s thirteen years as a Japanese national conducting import/export business in Panama was enough to warrant suspicion but Amano admitted,

I had lots of reasons to give them concern. For instance, I like a good view. I built a house outside the city on a mountainside, with a view of the entire canal all the way to the entrance. I could see every ship come and go. Naturally, the Americans knew all about that… Also, nearby in Costa Rica’s Puntarenas Harbor, I owned the Pacific Fishery Company. That sounded like a big company, but it was just a $12,000 company. One of my fishing boats was named the Amano Maru, with only a 250 horsepower engine. I had it built in Japan and sailed across the Pacific. It held a crew of 16 Japanese fishermen, catching tuna only 200 miles from Panama. Of course, America thought it was a spy ship.

Amano went on to list his ranch in Concepcion, Chile with a view of Talcahuano Military Harbor and his frequent business travel as further causes for concern. But there was more. Amano enjoyed photography. He boasted,

by the canal there was a Balboa photography club. The members were all Americans and I was the only Japanese. I won the most prizes – 25 times for best in show. If you’re a spy, photography is an important requirement and I had that ability.

In addition, Amano authored several books and “all my American acquaintances knew that I had the ability to transmit reports.” But it was Amano’s ship that attracted the most suspicion and provided rich material for authors of popular spy tales.

Richard Wilmer Rowan, characterized by his archivists as both a legitimate investigative reporter and a muckraking journalist, published Secret Agents Against America in 1939. In a chapter entitled “How Safe is the Canal Zone?” Rowan charged that Amano was a secret agent “whose real profession seems to be a secret to no one.” According to Rowan, Amano was arrested in Colombia and imprisoned in Nicaragua following an espionage charge by an unspecified country but he “was enough of a Chilean millionaire to talk his way out of a Nicaraguan jail.”

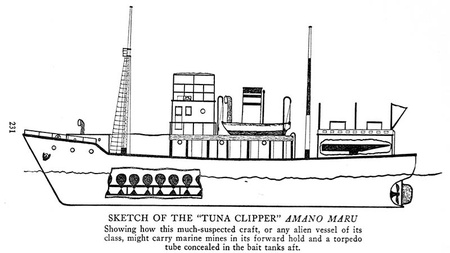

This Japanese adventurer’s private boat, the Amano Maru, which he describes as a ‘tuna clipper,’ is the kind of fishing craft that serves caviar at meals. Rowan offered the following sketch of the vessel. Its caption, with the qualifier “might,” exposes the purely speculative nature of the illustration:

Another 1939 publication, Richard Spivey’s Secret Armies: The New Technique of Nazi Warfare, described the Amano Maru’s luxurious appointments. “With a purring diesel engine, it has the longest cruising range of any fishing vessel afloat, a powerful sending and receiving radio with a permanent operator on board and an extremely secret Japanese invention enabling it to detect and locate mines.” Spivey also mentioned the cancelled ship registry, its new location in Puntarenas Harbor, Costa Rica, and Amano’s predilection for expensive cameras.

The FBI and the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), working under diplomatic cover to find evidence of espionage, relied on information that turned out to be uneven at best and completely false at worst. These organizations paid Panamanians for information. However, their method of compensation rewarded quantity over quality, resulting in unreliable intelligence from the informants.

**All photographs are courtesy of the author.

© 2010 Esther Newman