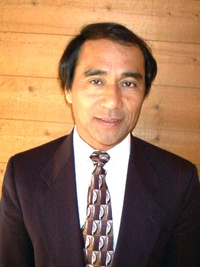

What is it like to be a Japanese American in Europe, far from one’s family and origins? How does it feel mingling mostly with Caucasians in their culture and language? Since the summer of 1966, I have lived, studied, and worked in numerous European countries.

My experience has been very positive, a nice compliment to my years of studies and professional work in Japan, Asia and Latin America. While Europe is the source of our political, religious and educational systems, it is now undergoing a major transformation due to immigration and the founding of the European Union. As a mirror to the United States, I find Europe much more open than Japan and many Asian countries to newcomers. Once a rarity, minorities are now commonplace in most European countries and can teach us much about our own experiences. My experiences in Europe over the past 40 years have given me a window into its changing demographics and attitudes toward racial and ethnic minorities.

In 1966, I was an American Field Service (AFS) summer exchange student to Bochum, Germany in the thriving Ruhr Valley. As a rare Asian, I drew constant stares, but my host family, friends and classmates were extremely warm and friendly. Only my AFS mother spoke English so I became fluent in daily German. Fortunately, I had studied German every Saturday mornings for two years, instead of Japanese, so German came quickly. During August, I joined a Catholic youth group to Austria, where we wore lederhosen, sang German songs like “Edelweiss,” played soccer and picked blackberries - just like in “The Sound of Music.” This experience served me well since Siemens, Bosch and other German electronics makers were my high-tech clients during the 1980s.

In 1969, I received a Carnegie Foundation grant through Yale to teach English to Venezuelan and international students at an American school in Caracas, Venezuela, where I lived with a Spanish family from Madrid in the nearby shantytown and learned Castellano and street lingo. Venezuelans are very warm and friendly, calling me “Chino” as they do all Asians since the only Asians around were Chinese running grocery stores. People were very curious about my cultural origins since many Venezuelans are multicultural and multiracial. Again, this experience served me well since I was hired in 1980 by Bechtel to help Lagoven, the national oil company, prepare urban plans for a major oil sands project in eastern Venezuela. I was hired on the spot since few Americans spoke Spanish and had worked in Latin America. However, a poor peasant provoked me to study in Japan, saying: “I’m poor, but I know my culture and people. You’re educated, but I feel sorry for you since you don’t know your own cultural roots.”

So after spending a year in LA on a Coro Foundation grant, where I helped draft the Manzanar plaque with the Manzanar Committee, I spent 1973 to 1975 in Okayama, Japan, the sister city of San Jose, my hometown, teaching English at Okayama University and junior high schools, studying Japanese and discovering my roots. It was like a homecoming and I felt I had lived in Japan before. The culture felt so familiar, even though I had never been to Japan. My Kobe relatives were so much like my Oakland grandfather and grandmother that it felt like déjà vu. I guess my years of hanging around Japantown as a child deeply imprinted Japanese culture into me. Perhaps the most vivid experience was touring Kyoto temples. Suddenly, I felt a big whoosh rush into me as if a huge void had been filled and I was completely whole. Now I realized that I came from a long, deep cultural heritage. Besides making lots of friends, I learned to read over 2,000 kanji and read books on urban planning in Japanese, which was later useful when I did research on Japan’s Technopolis program in 1984 to 1990.

I also met my future wife Muneko, with whom I swapped language lessons, during my time there. She came from a modest family and worked at a credit bank. A college graduate from a Nagoya university, Muneko was very intelligent, kind and articulate, openly disagreeing with guys in our student discussions, unlike her female peers. I was impressed, especially she spoke beautiful Japanese. Little did I know that we would marry and I would use Japanese often in my high-tech work in SiliconValley.

Since 1982, I’ve probably advised over 100 major Japanese companies on marketing and business strategies, often in Japanese at their Tokyo and Osaka headquarters. My two years in Japan, plus my constant studying of Japanese, paid off since I feel very comfortable working with Japanese managers and entrepreneurs. Often, Japanese ask me when I emigrated to America since I connect with them on a gut level, or “haragei.”

After leaving Japan, I visited my girlfriend in Paris, auditing history and literature classes at the Sorbonne and urban planning at Val du Marne. Unlike Japanese and Spanish, my French speaking is passable at first, but I can converse and give presentations after I’ve been in France for three or four days. Currently, I’m co-producing an indie movie with my dear friends in Normandy so speaking, reading and writing French comes in handy. Having lived with French friends and families, many French say that I’m very “continental” like a European because I can connect with them on an emotional level.

One reason I’m able to connect is that I listen to my gut and intuition overseas since most people think very differently from Americans, who tend to be more open, pragmatic, legalistic, and frank. Although Japanese and French cultures are diametrically opposed—Japanese culture being more indirect and non-verbal, while the French people I meet (mostly college graduates) tend to be very intellectual and philosophical—both cultures are very traditional and culturally deep, which I enjoy. Many Japanese nationals have traumatic experiences in Europe, but that has to do with their lack of international experience and being a minority overseas. Being American, I’m a minority in a country controlled by Caucasians (like Europe) and more exposed to many cultures and races so Europe is not that different. Indeed, my first few months in Japan were more of a personal shock since everyone was Japanese and there were almost no foreigners in Okayama, a situation I had never seen before. Japan is indeed a cultural island, which discourages immigration.

Since 1982, I’ve been providing market research and business strategy consulting to major high-tech corporations from Silicon Valley, Japan, Asia and Europe. In Europe, I had a dozen clients in France, Germany, Holland, Austria, Italy, England, and Scotland, which I visited annually, so speaking French and some German has been incredibly useful. Now I must learn Swedish, Italian, Arabic and Chinese to prepare for the future. I love learning foreign languages and cultures, which are keys to really understanding people. I believe Americans should learn as many foreign languages as possible since this is a global economy and new opportunities will come heavily from abroad.

Since January 2008, I’ve been working in Jonkoping, Sweden as the Associate Dean of Business Creation for the Jonkoping International Business School (www.jibs.se). It’s a small city of 130,000 people, but very entrepreneurial so I feel right at home. Although Swedish is similar to German, I still have a difficult time understanding people, but I’ll learn by practicing. Like most European towns, Asians stand out so people look or stare at me out of curiosity, but if one speaks the local language, people smile and open up like anywhere in the world.

I believe “when in Rome, do as the Romans do” is a good rule, so I must learn Swedish. My mission here is to inject some Silicon Valley DNA into the business school, in exchange for the Swedish lifestyle. What a bargain! Since my wife died, my daughter finds it lonely being the only child, so she will join me after graduating from UC Santa Cruz this June. She will study fashion management and intern in Paris at a friend’s shop, so we’ll be imbibing the cultures and wines. We’re very close, running around and spending a lot of time together to fill the huge void left by my wife’s passing, so it will be fun enjoying Europe together. Also, since the Iraq war, I feel a personal mission as an American to help other nations in a peaceful way through education and training. Our business school will train educators and students from the Mideast, India, Europe, and Latin America through our 350 partner universities.

Europe is struggling with racial and religious conflicts, skinheads and intolerance like many other nations experiencing massive immigration. On a personal level, I’ve never experienced any outright hostility or discrimination. Open discrimination is usually the result of many immigrants moving into a region within a fairly short period. Most Europeans I’ve met are friendly, especially if I try to speak their language. As on the East Coast, Japanese Americans are a rare breed so we attract more curiosity than anything else. As elsewhere I’ve been, people want to know if I’m from Asia. When I tell them I’m California of Japanese origins, they’re curious and want to know how my grandparents came to America and whether I still speak Japanese and have close ties with my Japanese relatives. Basically, they want to know whether I’ve retained my roots, just like the peasant farmer in Venezuela.

Sometimes I feel like a “Martian” landing in an unfamiliar world with few Asian Americans, not unlike moving to a small town in Minnesota or Florida. In that sense, Japanese Americans in Europe are like the first Japanese to visit America—rare sojourners from a distant shore. But I’m not the only one. In this era of rapid globalization, there are more solo travelers and migrants moving far from home in search of new opportunities and experiences.

Welcome to the 21st century.

* This article was originally published in Nikkei Heritage Vol. XIX, Number 1 (Spring 2008), a journal of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2008 National Japanese American Historical Society