Introducción

La primera versión de este artículo fue escrita en 1993 para el libro “Cultura, identidad y cocina en el Perú”1. En aquellos momentos, aunque ya conocida, la cocina nikkei peruana no había alcanzado aun la difusión y el reconocimiento de los que actualmente goza, al igual que el caso de la cocina japonesa en su excepcional dimensión internacional en el presente. A pesar de que, desde entonces, las publicaciones especializadas con respecto a las comidas japonesa y nikkei se han multiplicado, la reproducción de este artículo – con algunas actualizaciones - sería pertinente, puesto que trata sobre la presencia más amplia de los nikkei en el rubro de la cocina peruana, desde casi la incursión de los inmigrantes japoneses en las ciudades peruanas a principios del siglo 20 hasta momentos más recientes en que, quizás, tal presencia haya alcanzado su máxima expresión con la cocina nikkei.

Ya en los inicios de la década de 1990 podíamos afirmar - y en el presente con mayores evidencias – que en el espacio de la cocina y comida se estaban produciendo de manera no conflictiva, y aun armoniosa, las mezclas y fusiones que en otros aspectos no habían sido observadas, como si aquél fuera el más abierto y democrático dentro del campo de la cultura.

En el Perú actual, un indicador del vasto proceso de mestizaje puede ser observado, precisamente, en la variedad y mezcla en la cocina y comida, especialmente en la región costera. A través de su historia, a las tradiciones culinarias locales se fueron sumando las de origen europeo y las creaciones de la población de origen africano en distintos momentos desde la conquista española. A partir del siglo 19, con la llegada sucesiva de chinos y japoneses, el elemento asiático es también incorporado.

Entre el elemento asiático, la comida china – conocida popularmente como “chifa” en el Perú – ha sido y es, indudablemente, la que mayor difusión y aceptación ha logrado en el país, quizás por su mayor antigüedad y su pronta adaptación a los gustos locales. Esta comida es ya parte de los menús caseros y cotidianos desde hace varias décadas y los restaurantes de comida china o “chifas” se cuentan por miles en todo el país. Es más, productos como el “siyao” o salsa de soya china se expenden en las bodegas, mercados y supermercados locales, debido a su demanda desde todos los sectores sociales para su utilización en la cocina familiar.

Las distintas vertientes de la presencia nikkei y japonesa en la cocina peruana

Entre fines del siglo 20 y los inicios del presente, numerosos aspectos de las culturas se vienen modificando de manera acelerada a nivel mundial, al ritmo de la globalización y de los desarrollos tecnológicos, con una circulación de información, gente y productos aparentemente sin precedentes en la historia. Según algunos observadores, las particularidades culturales irían desapareciendo, por lo menos de aquellos lugares y sectores más centrales de los circuitos del mercado y consumo. El registro de los antecedentes y cambios en esos aspectos, entonces, sería oportuno para la memoria presente y futura.

Con relación al tema específico de la presencia nikkei y japonesa en la cocina del Perú, podemos identificar hasta cuatro vertientes que fueron surgiendo en distintos momentos y que, hasta el presente, mantienen ciertos límites entre sí. No obstante, debido a la tendencia a una fusión cada vez mayor entre cocinas y comidas, tanto por la utilización de ingredientes y de procesamientos o de cocción de alimentos comunes a varias cocinas, como por la proliferación de variedades dentro del fenómeno de la denominada “cocina de autor”, quizás en un futuro cercano tales límites serán menos perceptibles y aun se diluyan.

De las distintas vertientes para el caso nikkei - japonés, la última en aparecer fue aquella que en las tres últimas décadas del siglo 20 empezó a evidenciarse como un nuevo tipo de comida en el país y a la que el poeta y gastrónomo peruano Rodolfo Hinostroza bautizó como “Cocina Nikkei”. Tal cocina se caracterizaba - en sus inicios - por la utilización de productos marinos (mariscos y pescados) y otros ingredientes de origen asiático, además de formas de procesamiento y cocimiento usuales en algunas regiones del Japón y al hecho de que sus creadores eran y son de ese origen.

Al lado de esa comida difundida a través de algunos restaurantes en Lima, coexiste otra reconocida internacionalmente como de comida japonesa y que en el Perú solía ser preparada por chefs o “itamaes” japoneses – varios de ellos formados en escuelas profesionales del Japón – en restaurantes especializados desde la década del 60. Los platillos denominados sushi, sashimi, tempura, sukiyaki y yakitori eran los que principalmente identificaban a este tipo de comida.

Una tercera variante, con relación a la comida con raíz japonesa, la encontramos en los hogares de las familias de este origen. En ella era y es posible encontrar una mayor variedad y variantes de platillos, traídos por los inmigrantes como parte de los bagajes culturales desde las distintas regiones y prefecturas del Japón. En esta, muy posiblemente, se encuentra el origen y la fuente principal de la hoy reconocida “cocina nikkei”.

La cuarta vertiente, y la más antigua en presencia pública en el Perú, se halla en los restaurantes generalmente en barrios populares de Lima, de propietarios de origen japonés que – desde las primeras décadas del siglo 20 – difundieron la cocina criolla y popular peruana en general, en algunos de cuyos potajes puede reconocerse algún ingrediente o estilo particular de preparación, frente a los recetas originales peruanas. Por ejemplo, la preparación del cebiche peruano con cortes tipo sashimi para el pescado y el tiempo breve del marinado en limón, así como la incorporación de insumos japoneses como el glutamato monosódico (el sabor “amami”, conocido con la marca “Aji no moto” en el Perú) y el shoyu o salsa de soya japonesa en distintos platillos de la cocina criolla peruana, como el lomo y los tallarines saltados.

Los restaurantes nikkei y japoneses en el siglo 20

La presencia japonesa en la cocina peruana es tan antigua como la inmigración de este origen. Los primeros inmigrantes japoneses que arribaron al Perú entre 1899 y 1923 fueron contratados como mano de obra para las haciendas costeñas de caña y algodón. La permanencia de la mayoría en las labores agrícolas sería sólo temporal, pasando luego a las ciudades. Las nuevas oleadas de inmigrantes llegados entre 1924 y 1936 se dirigieron también hacia las ciudades y con mayor frecuencia a las provincias de Lima y Callao. En ellas, algunos japoneses adquirieron establecimientos comerciales por traspaso de antiguos inmigrantes chinos e italianos, principalmente de cafetines y bodegas.

Desde las primeras décadas del siglo 20 empezó a ser parte del panorama cotidiano de las ciudades peruanas la presencia de japoneses conduciendo peluquerías, restaurantes o “fondas” (pequeños restaurantes), cafetines, bodegas, carbonerías, bazares, panaderías, entre otros, dentro de la creciente actividad urbana. De esos distintos rubros, los restaurantes y similares han sido los que con mayor frecuencia y persistencia han concentrado a los inmigrantes japoneses y sus descendientes a lo largo de su historia hasta el presente.

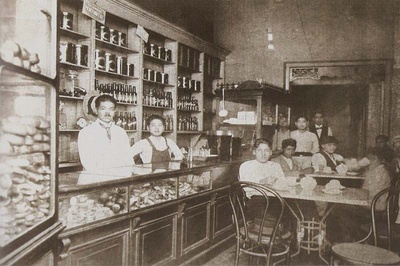

Watanabe, José, Morimoto, Amelia, Chambi, Óscar.1999.“La Memoria del ojo. Cien años de Presencia Japonesa en el Perú”. Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso de la República; p. 63: Salón de café del Sr. Tokuchi y hermanos en Lima, circa 1920.

Algunas estadísticas de distintos años corroboran tal hecho. De acuerdo a fuentes diversas, por ejemplo, en 1931, de 1 212 establecimientos de japoneses registrados, 122 eran restaurantes y 264 cafeterías. En 1938, de 878 establecimientos, 158 eran cafeterías y cafetines y 92 “picanterías” y “fondines” (pequeños restaurantes). En 1966, de acuerdo al primer censo nikkei2, los establecimientos de comidas y bebidas de propietarios de origen japonés sumaban 1 047, constituyendo la cuarta parte del total. En 1980, la misma población contaba con 944 restaurantes y similares en Lima y 200 en otras provincias y, finalmente, según el censo nikkei de 19893, estos propietarios contaban con 1 032 restaurantes y similares en Lima y 310 en otras provincias.

Fuente: Watanabe, José, Morimoto, Amelia, Chambi, Óscar.1999. La Memoria del ojo. Cien años de Presencia Japonesa en el Perú. Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso de la República; p. 89: Asociación de Propietarios de Restaurantes en Lima, Presidente (al centro, sentado) Sr. Kunihiko Hayashi, década de 1930.

Los restaurantes de los inmigrantes japoneses y de sus descendientes surgieron inicialmente en los barrios populares y destinados a este sector. Los platillos que en ellos se expendían no eran aquellos que los japoneses solían preparar en sus hogares, sino los de consumo cotidiano por la población local y que con prontitud aprendieron a confeccionar. Así, los “fonderos” japoneses se familiarizaron con potajes como el “cau cau”, la “papa a la huancaina” los popularmente denominados “tallarines rojos” (de salsa de tomate) y “verdes” (pesto), el lomo y los tallarines saltados.

En la década de 1960, simultáneamente a la aparición de inversiones japonesas directas, surgieron también los restaurantes de comida japonesa, aunque su clientela solía ser casi exclusivamente japonesa y nikkei. En la década de 1970 varios de los propietarios nikkei de restaurantes empezaron a trasladar sus establecimientos hacia barrios medios y medio altos de Lima, paralelamente a la adopción de otras especializaciones en cocina. Las “parrilladas” (de carnes de res principalmente) y “pollerías” (pollos enteros, cocidos con fuego de brasas de carbón o de leños) que, aunque no creadas ni introducidas por los nikkei, se difundieron rápidamente a través de sus restaurantes.

Al mismo tiempo, desde esa década, empieza a evidenciarse un tipo de comida que fusionaría el sabor criollo peruano (de la costa) con el japonés, lo que hoy se reconoce como cocina nikkei peruana. La característica principal de esta cocina es el uso de pescados y mariscos con ingredientes locales y la incorporación de otros de origen asiático como el kión (jenjibre), sillao o shoyu (salsa de soya) y la cebolla china.

Para el desarrollo de la cocina japonesa así como de la nikkei se presentaron condiciones como es el cultivo de algunos vegetales y la fabricación de productos como la pasta (miso), salsa (shoyu) y queso de soya (tofu), de fideos especiales (udón, somen), encurtidos, en las que varias familias de origen japonés se especializaron en el Perú.

La comercialización de tales productos se realizaba en los alrededores del Mercado central de Lima principalmente. Los productos fabricados en el Perú, así como muchos otros importados desde Japón, desde la década de1950 se encontraban en tres establecimientos comerciales, las Casas Koga, Ebisuya e Ikemiya. Actualmente y desde la década de 1980, en los Mercados de Palermo en el distrito de La Victoria y en el de Jesús María existen puestos dedicados al expendio de vegetales y otros productos e insumos japoneses producidos en el Perú, así como de fabricación japonesa.

Dentro del consumo de la población nikkei con alguna persistencia se hallan también los dulces y pastelillos japoneses que con mayor frecuencia se preparan para las festividades japonesas o comunitarias y para los rituales funerarios, como parte de las ofrendas para los fallecidos. Los pastelillos, de pequeñas dimensiones o “wagashi”, son generalmente confeccionados con pasta de arroz, frijoles y azúcar y su fabricación solía estar en manos de algunas familias desde hace muchas décadas. La más antigua y conocida fue la Casa Kotobuki de la familia Miyata en el Cercado de Lima.

Los restaurantes japoneses y nikkei en Lima

Fuente: Carátula del libro “Toshiro Konishi” (“Toshiro’s Japanese Restaurant”).2007. Colección “Nuestros grandes chefs”, Tomo 4. Lima: Orbis Ventures SAC.

En el presente, en Lima, en donde existe una concentración de restaurantes de propietarios de origen japonés, pueden ser observados y degustados los distintos tipos de cocina practicados por los nikkei y japoneses. En los barrios populares del Cercado de Lima, Breña, La Victoria, Jesús María, Surquillo, entre otros, eran y son aun frecuentes los restaurantes de comida criolla, y popular en general, de propietarios nikkei, como “Don Bosco” en el distrito de Jesús María y “Huanchaco” en La Victoria. Entre los que fueron trasladados o se abrieron como nuevos establecimientos en otras zonas más exclusivas de la ciudad se encontraban “Los años locos” y “Dallas” en San Isidro, ambos dedicados a carnes, parillas. Los restaurantes de comida japonesa, asimismo, además de estar dedicados en un inicio al público japonés y nikkei, solían orientarse casi exclusivamente a un público de nivel socioeconómico medio alto y alto. Entre estos últimos, por ejemplo, los restaurantes “Mikasa”, “Fuji”, “Ichiban”, “Matsuei” y el del popular chef japonés Toshiro Konishi en los distritos de San Isidro y Miraflores. En los últimos años del siglo 20, varios de los restaurantes mencionados fueron cerrados por razones diversas; no obstante, al inicio del nuevo siglo, nuevos establecimientos de sushi y de cocina nikkei han aparecido en la capital peruana, sobre ellos y sus chefs se tratará en la segunda parte de este artículo.

Notas

1. Olivas Weston, Rosario (Compiladora). 1993. Cultura, identidad y cocina en e Perú. Lima: Universidad San Martín de Porres; pp. 257- 270.

2. Sus resultados fueron publicados en japonés en: Zai Peru Nikkeijin Shakai Jittai Choosa Inkai.1969. Peru kokuni okeru nikkeijin shakai.- Tokio, idioma japonés (Censo 1966).

3. Morimoto, Amelia. 1991. Población de origen japonés en el Perú: Perfil actual.- Lima, Comisión Conmemorativa del 90° Aniversario de la Inmigración Japonesa al Perú (Censo Nacional Nikkei 1989). La información sobre el año 1980 es parte de un informe de investigación, realizado por la autora con el apoyo de la Fundación Ford en tal año.

* Este artículo se publica bajo el Convenio Fundación San Marcos para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Cultura de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos - Japanese American National Museum, Proyecto Discover Nikkei.2009- 2010. Lima- Perú, Abril 2010/Amelia Morimoto, editora y coordinadora.

© 2010 Amelia Morimoto