Two years ago a photograph changed Kaori Flores Yonekura’s life, a Venezuelan filmmaker whose grandparents were Japanese. It was a photo of Mr. Takeuchi, who at the time of the photograph was president of the Nikkei Association of Venezuela.

What was it about the photograph that changed Kaori? It showed some Japanese dressed in rural garb and eating arepas (bread made of corn flour) on a hillside. Kaori discovered that the people in the photograph were in Ocumare del Tuy, a town located some forty minutes from Caracas, and that the photograph dated to World War II.

Unlike what happened in Peru, the Japanese were not deported from Venezuela. The Venezuelan government, however, decided to relocate the Japanese to Ocumare del Tuy. While not exactly prisoners, these folks were monitored.

After seeing the photograph and becoming acquainted with its history, Kaori made a decision. “I began to do some research and decided to do a history of Japanese immigration but one that used my family as the primary thread,” she recalls.

Thus Nikkei was born, a documentary to which she has dedicated herself, and that has taken her to Japan and Peru. Why Peru? The South American side of her grandfather’s story—Rinzo Yonekura—began in Peru.

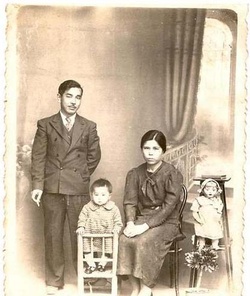

Rinzo Yonekura Yonaga, Kazumi (Rosa), Kumezi Kobayashi, grandfather, Aunt and Grandmother of Kaori (Photo cortesy of Kaori Flores Yonekura)

In 1921 Rinzo and his cousin Yuzo left Yokohama for the San Agustín Hacienda. They both stayed in Peru until 1939. One day Yuzo crossed the Rímac River; the following day Rinzo did the same. Both cousins swam away from Peru forever.

What pushed them to leave? Kaori doesn’t know for sure, but poor working conditions, which were common in those days, were probably the primary reason that both men took such risky action.

There is a gap in Rinzo’s life from the time he left Peru and the time that he arrived in Venezuela. “My family has no information about what happened to my grandfather after he crossed the river. As I know so little about this story, I am trying to piece together the Peruvian aspects, particularly how the Nikkei lived there. What happened when they left the haciendas, when did the work contracts come to an end, when did the Nikkei start their own businesses, and when did the looting start. My grandfather left just before the looting began,” explains Kaori.

Yuzo was the first to arrive in Venezuela. From there he contacted Rinzo and told him that he could come join him there. Rinzo and his wife, who had come from Peru in 1937, arrived in Venezuela by crossing the border with Colombia; they went to live in the city of San Antonio del Táchira.

When the war erupted the Japanese who had been living in Caracas had to move to Ocumare del Tuy, although Kaori’s grandparents were allowed to stay in San Antonio del Táchira but under surveillance.

“The police were everywhere. My grandfather had a few friends. Since he didn’t speak Spanish very well, and the locals had never seen Asian peoples before, most stayed away and avoided contact with him. He had a radio, and when he began to listen to the news, he was accused of being a spy and imprisoned. Those three friends of his went to the jail and told the authorities that he was not a spy and that they should set my grandfather free. If the authorities should find evidence of espionage, his friends continued, then the authorities could also imprison them. They guaranteed his life with theirs, and he was set free,” Kaori tell us.

Something happened that helped improve Rinzo’s relationship with the city. One day the Táchira River rose dangerously above its banks, carrying several people with it. Acting decisively, Rinzo jumped into the river and saved them. His heroic action garnered the sympathy of the town’s residents; Rinzo was allowed to move around town more freely. The Japanese man whom people viewed with misgivings had won the right to become a citizen of his adopted country. His children and grandchildren likewise enjoyed the same rights of Venezuelan citizenship.

* This article is made possible by an agreement between the Japanese Peruvian Association and the Discover Nikkei Project. It first appeared in the journal Kaikan, volume 47, July 2010.

© 2010 Asociación Peruano Japonesa y Enrique Higa Sakuda / © 2010 Fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa y Kaori Flores Yonekura