その2 >>

激動の10年に重ねた青春期

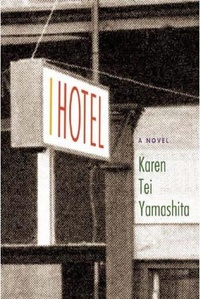

I Hotelとは、かつてサンフランシスコのマニラタウンにあったInternational Hotel(国際ホテル)のことで、主にフィリピン系の低所得者層が暮らすアパートだった。

1920年代によりよい生活を求めてアメリカにやってきたフィリピン人にとって、低料金で利用できるI Hotelは不可欠な存在だった。1950年代には、このホテルを中心として約1万人のフィリピン人が暮していた。

1968年の12月、ホテルのオーナーであるミルトン・マイヤー社は、ビルを駐車場にするので立ち退くよう、住人に通達した。この頃には、マニラタウンは、I Hotelがある一角だけになっていた。高齢者のために安い宿泊施設を提供してきたこのホテルを守ろうと、労働団体、教会、活動家などが抗議運動を起こした。その結果、ミルトン・マイヤー社が統一フィリピン協会(UFA)にホテルをリースすることになったが、その契約の前日にホテルで不審火が発生し3人の犠牲者が出た。契約は中断された。放火の疑いが強かったが、マイヤー社もサンフランシスコ市も事故扱いとし、市は同社に建物の取り壊しを命じた。その後の運動でホテルが期限付きでUFAにリースされたが、1977年8月4日の未明、武装した警官300名が、ホテルを囲む数千人のバリケードを突破して、最後の50人の住人が強制退去させられた。

I Hotelというと、中国系の映画監督であるカーティス・チョイが1983年に制作したドキュメンタリー、「The Fall of the I-Hotel」(国際ホテルの陥落)を思い起こす。リアルタイムでカメラを回して作られたこの作品はアジア系コミュニティで話題になり、チョイは、アジア系のドキュメンタリー映画として一つの金字塔を打ち立てた。ヤマシタの『I Hotel』の最終章で描かれる強制退去の場面は、「国際ホテルの陥落」さながらで、活字にしても迫力を感じさせる。

だが、ヤマシタが描くI Hotelは、単にこのホテルの顛末にとどまらない。物語は、アジア系アメリカ人の市民運動がはじまった1968年からホテルが陥落した1977年の10 年間に、アジア系アメリカ人のコミュニティでどんなことが起き、人々がどんなことを考えてきたのかを克明に描いている。

手法は前著の『サークルKがめぐる』と同じで、わかりやすく時系列に1年ごとの出来事を並べており、エッセイ、物語、戯曲、映画の脚本、漫画、イラストなどが入り混じる。さらに、孔子、マルクス、エンゲルス、レーニン、マルコムX、チェ・ゲバラ、フランツ・ファノン、フェルディナンド・マルコス元フィリピン大統領、イメルダ・マルコス夫人、ネルソン・マンデラ、リチャード・ニクソンらの数々の言葉の引用が散りばめられており、壮大なスケッチブックを手にしている感がある。

さまざまな固有名詞は、差し支えないと考えられる場合は実名で、そうでない場合は偽名が使われている。偽名の場合は実名を推測するマニアックな楽しみもある。この本を書くにあたって、10年取材したというだけあって、その量たるや圧倒的で、アジア系アメリカの歴史や文化に多少なりとも関心を抱いてきた私も知らないことが多く、読むのにひどく手間取った。

手を焼きはしたが、思った。ヤマシタが生まれたのが1951年。1968年から77年といえば、彼女が高校生から大学生、そしてブラジルに赴いた最も多感な時期である。この本は単にアジア系アメリカ社会が最も激動した10年を記録し紹介しているのではなく、その時代を自分がどう生きてきたかを振り返り、今の自分の位置を確認しているのだろうと。そう思うと、彼女のことが少しだけわかった気がした。

徹底した取材の中で、対象者の声を選択しながら、あるいは選択を余儀なくさせられながら、重層的な物語を紡いでいく。それは、ヤマシタにとっての歴史であり、真実であるが、読者もその真実の一部を共有し、自分を振り返ることができる。読みながら、私もその作業をした一人だった。

以上、1年と少し、日系アメリカ人をとりあげて、彼らの視点が私たち日本人にも何らかの参考になるのではないかという思いで連載を続けてきたが、ひとまず、今回をもって連載の最後にしたい。お付き合いしていただいた方、ありがとうございました。

(敬称略)

カレン・テイ・ヤマシタの作品(英語)

* Through the Arc of the Rain Forest , Coffee House, 1990

邦訳『熱帯雨林の彼方へ』白水社 1994

* Brazil-Maru, Coffee House, 1992

抄訳「ぶらじる丸(抄)」『すばる』2008年7月号

* Tropic of Orange , Coffee House, 1997

抄訳「オレンジ回帰線」『10+1』 No.11 1997

* Siamese Twins and Mongoloids, Yellow Light, Temple University, 1999

邦訳「シャム双生児と黄色人種」『私の謎』岩波書店 1997

* Circle K Cycles , Coffee House, 2001

抄訳「サークルKがめぐる」www.cafecreole.net 1997

* I Hotel , Coffee House, 2010

参考資料

* 『誇りて在り「研成義塾」アメリカへ渡る』宮原安春 講談社 1988

* 「特別インタビュー カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ」『時事英語研究』1995年7月号

* 「作家のラティテュード(緯度=自由度)」 今福龍太+カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ 『10+1』 No.11 1997

* 「浦島玉手箱博物館」カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ『約束の大地/アメリカ』 みすず書房 2000

* 「旅する声」カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ 『「私」の探求』岩波書店 2002

* 「血液型」カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ www.cafecreole.net 2004

* 『アジア系アメリカ作家たち』 杉浦悦子 水声社 2007

* 「カレン・テイ・ヤマシタの「ブラジル丸」における日系ブラジル移民の挑戦:エコフェミニズムからの考察」島津信子 『九州工業大学学術機関リポジトリ』 2007

* 「紳士協定」カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ 『すばる』2008年7月号

* 「移民の声の共同体」今福龍太『すばる』2008年7月号

*本稿は、時事的な問題や日々の話題と新書を関連づけた記事や、毎月のベストセラー、新刊の批評コラムなど新書に関する情報を掲載する連想出版のWebマガジン「風」 のコラムシリーズ『二つの国の視点から』第13回目からの転載です。

© 2010 Association Press and Tatsuya Sudo