The War Between Us, a Canadian TV-film directed by Anne Wheeler and released in 1995, is a considerably more sophisticated and critical film than Hell to Eternity (from a different generation, in fairness). It recounts the events of the wartime removal of 22,000 West Coast Japanese Canadians by the Canadian government. In February 1942, one week after U.S president Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, Canadian Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King ordered all people of Japanese ancestry, whether aliens or citizens, removed from the Pacific Coast of Canada. After being taken from their homes by an emergency federal agency, the British Columbia Security Commission (BCSC), the bulk of those removed were forced into settlements in abandoned mining towns in eastern British Columbia’s Slocan Valley. Unlike in the United States, the Japanese Canadians were given no financial assistance other than housing, and a bare minimum of elementary schooling for children and medical care. Instead, Ottawa forced the families to pay the expenses of their confinement. In order to extract money from community members and also to ensure that they would not return to the West Coast, in 1943 an official custodian of “Enemy property” sold off all the real estate and personal properties of the Japanese Canadians, generally at bargain prices. As the war drew to a close, the government perpetrated a further injustice by forcing Japanese Canadians the “choice” of moving, immediately and permanently, away from the West Coast. Those who preferred to stay in the camps and settlements where they had been placed were deemed to have 'agreed' to be deported to Japan, irrespective of citizenship, as soon as the war was over. While Japanese Canadians and their allies eventually were able to have this unjust policy reversed, thousands of Japanese Canadians were bullied into surrendering their citizenship and their country.

* * * * * spoiler alert * * * * *

The principal action of The War between Us takes place in New Denver, the backwater town in the east of British Columbia where thousands of Japanese Canadians from the Pacific Coast are forcibly resettled in mid-1942 by the BCSC. Ed Parnham (Robert Wisden) and his neighbors are initially reluctant to accept the “Japs”, but they quickly recognize that it is the only way to improve the devastated economy of their abandoned mining towns. Profiting from the business boom fostered by the presence of the Japanese, his wife Peg Parnham (Shannon Lawson) and a friend open a general store to sell clothes to the inmates. Meanwhile, the action moves to Vancouver, where we see Mr. Kawashima (Robert Ito), a prosperous businessman, and his daughter Aya (Mieko Ouchi), who works in his office. After war is declared, they are faced with prejudice and are forced to surrender their brand-new car to the authorities. Soon they are removed by official order. Mrs. Kawashima (Ruby Truly) must quickly pack the family’s belongings.

The Kawashimas, along with other families, arrive in New Denver and proceed to enter the freezing and dilapidated shack they have been assigned. In order to pay for supplies and support the family members while they await income from the rental of their house and of Mr. Kawashima’s business, Aya Kawashima is forced to take work as a maid (and later shop assistant) for the Parnhams. Although the members of the Kawashima family initially try to make the best of their situation amid the hostile surroundings, they are embittered by the news that the federal government has confiscated their belongings. Mr. Kawashima, a World War I veteran, is so embittered by his treatment that he insists on taking the family and repatriating to Japan after the war.1

In this film, as in white hero narratives, the main white characters, Peg Parnham and her husband, are humanized by their contact with the Japanese Canadians and grow. From being wary and ignorant, they turn into friends, and begin to criticize government policy—Ed eventually punches out Mr. Tom McIntyre (Kevin McNulty), the racist local representative of the BCSC because of his anger at the deportation policy—and question their complicity: “How did it happen? How did we end up on the wrong side?”2 However, the narratives offer twists on standard narratives via the inclusion of discordant gender and class elements. Also, whereas in both Come See the Paradise and Snow Falling on Cedars, like the old “passing” narratives, the romance is between a white man and a Nisei woman, what strains and ultimately unites the Kawashimas and the Parnhams is the romance between Aya’s brother Mas (Edmond Kato Wong), and the Parnhams’ daughter Marg (Juno Riddell).

In The War Between Us the whites do not, unlike Atticus Finch, step in at first to assist Japanese. Rather, it is the Japanese Canadians who come to the aid of the whites, since their town economy and their stores are dependant for patronage on Japanese Canadians (the Kawashimas permit Aya to go for work as a domestic, in a job they agree is beneath her, only because they refuse to go on relief or accept charity for reasons of self-respect). The Parnhams and their neighbors are portrayed as more rustic. There is a scene in which a white family celebrates the arrival of electric lighting, which the government has brought to the town in exchange for their sheltering Japanese Canadians. The urbanized Japanese Canadians look on and laugh scornfully at the joy of “the savages.” When Mas expresses his ambition to go to Harvard, Yale or Oxford, he is stunned that Marg has never heard of these places. When Aya begins helping Peg in her shop, and Mr. McIntyre patronizingly says that it will give her some useful experience, she loses her cool and reveals that she has a college degree and was used to doing the books at her father’s shipbuilding business.

Finally, The War Between Us violates the established narrative strategy in its complex portrait of the Japanese Canadians. There is generational conflict and family violence, and the question of loyalty is shown in complex fashion. For instance, there is a scene at the women’s bathhouse the Japanese community has built, in which a set of older women express their confidence that Japan will win the war because they have heard it said on the radio. In a memorable line, Aya says that her parents feel shame over their situation, and even her brother does, but that she refuses to feel shame over what has been done to her by the country she loves. She ultimately decides to accompany her parents to Japan, in order to help them resettle. When asked why she can’t simply pick up the pieces after the war and start over, she responds “There are no pieces.” By refusing to turn its Japanese Canadian characters into paragons of virtue or patriotism, the makers of The War Between Us keep them in the foreground and ultimately render more moving their plight.

Notes:

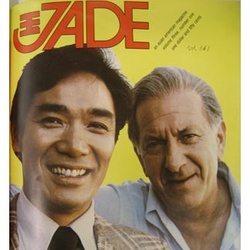

1. In another irony, Robert Ito, the Nisei actor who portrays Mr. Kawashima, was himself confined in the settlements as a teenager, and later resettled in Montreal, becoming a ballet dancer, before establishing a career in Hollywood, most notably as a Japanese American doctor on the TV series Quincy, ME.

2. Although the British Columbia Security Commission was actually dissolved at the end of 1942, and Japanese Canadians became subject to the decrees of the Ministry of Labour, in the film the government agency continues to be called the BCSC throughout the film.

© 2010 Greg Robinson