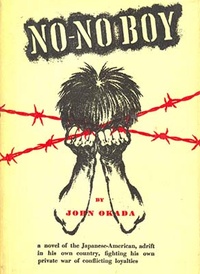

I’ve had the theatrical rights to NO NO BOY for a year and a half, and only now am I really willing to admit publicly (now that I believe I have a workable draft and now that we’re committed to producing it) that I’m tackling the adaptation of this seminal novel to the stage. It feels a little like saying, “We’re working on a stage adaptation of MOBY DICK; I think it’s going well!”

NO NO BOY by John Okada, first published in 1957, is something more than a book; it’s one of those works of art that transcends its actual form, becoming something much larger than just a novel. It was largely ignored during its first publication – most of its natural readership were likely more interested in starting and raising their families than they were revisiting a time that they were eager to put behind them. Asian America, as a term or concept didn’t yet exist, and without a market, the book went out of print and was largely forgotten, as was its author, who began work on another manuscript that was lost when his widow burned it after his death because no one would publish it.

The fact that this book had a controversial (within the Japanese American community) title probably didn’t help during those staid 1950s either. Even today, the term can spark bitter explosions amongst people who remain angry about the kinds of real life-or-death decisions they and their generation were forced to make during their young adulthood.

But the book struck a chord in a new generation of Asian American writers when it was discovered by writers Jeff Chan, Lawson Inada, and Frank Chin, who pushed for a new publication in the mid-1970s. When I read it, I felt like a bomb had exploded somewhere deep in my soul. Only a few years earlier, I had been rocked to learn about the internment camps and that my parents and their entire families had all been locked up, and had experienced the same kind of frustrations many people of my generation had experienced questioning parents who STILL felt this experience was better off buried in the past. Perhaps more frustrating still, I was angry, though my father, like many men of his generation, felt I had no right to be angry – after all, I wasn’t there, and their years of sacrifice and sublimation had made my cushy suburban upbringing possible, so what the hell did I have to complain about?

While grappling with the disconcerting knowledge of the ugliness and pervasiveness of hatred and bigotry faced by my parents only a few short years before I was born (and seeing some of it first hand when we moved to an all-white suburb of Seattle), I came upon this book and found within its pages an anger and a despair I knew had to be real; rage, confusion, and self-hatred that I knew had to burn somewhere in the tough hearts of many in my parents’ generation. I’d get little clues every once in a while in unguarded moments, especially from my father, who once told me that one of his friends killed himself after the war – he’d gotten through the internment and gotten through fighting in Europe, but when it came time to go home, he killed himself, telling my father before he did it that the past few years, their world had been turned upside down, “And now they want us to go home and lead a normal life? I don’t even know what that is.” Luckily, a lot of folks, like my father, were able to create those “normal lives” and hopefully found refuge and comfort there. But within the pages of NO NO BOY, John Okada captures the kind of nihilism so many young people feel even in the best of times – and what, indeed, is a normal life after all these characters have been through?

Okada also captures the tough-talking language of youth, as well. When Ichiro finally blows up at his militant pro-Japan mother, he grabs her by the hands and shouts “Balls! Balls! Balls!” He decks his own father in a blind rage before running off to see a friend, another No No Boy named Freddie, who’s banging a neighbor’s wife on a regular basis, if only because she doesn’t care where he’s been or what he’s done. When Ichiro presses Freddie on what it’s been like, Freddie tells him to get his head out of his fanny, finally exploding in frustration, “Okay, Itchy. It’s eatin’ my guts out too. Is that whatcha wanta hear? Is that why you came to see me? You miserable son of a bitch. Better you shoulda got a Kraut bullet in your balls.” Things get even rougher at the Club Oriental, where a character named Bull (he’s collapsed into the character of Eto in the adaptation) tells the crowd that “No No Boys don’t look so good without the striped uniform”, telling the dying veteran Kenji, “A friend of yours...is a friend of yours.”

The book is not without its problems. Chief among them is the fact that Ichiro is not really a No No Boy – at least, not in the sense that few, if any, No No Boys actually went to prison for their answers alone. Most were moved to Tule Lake where they were segregated for most of the remainder of the war. The men who went to prison were primarily draft resistors, mostly from Heart Mountain, though quite a few were sent to the McNeil Island Penitentiary out of Minidoka, presumably where Ichiro, who returns to Seattle, was interned with his parents. Okada, who was a veteran himself, listened to stories of vets, draft resistors, and No No Boys when he returned to Seattle, and most believe that he based the character of Ichiro on a draft resistor named Jim Akutsu. Why he chose to call his seminal novel NO NO BOY is an open question – whether he misunderstood the actual distinctions in a time where few people could see the big picture or simply decided to name his book after arguably the most divisive three words in the Nikkei community is something perhaps no one will ever know. But since the 1970s and the Redress movement of the 1980s, we’ve learned a lot about our own history, and it behooves us to do our best to get it right. Even so, after a recent reading at director Alberto Isaac’s home, a number of us, writer and actors alike, discovered how much knowledge we take for granted, but don’t really know for sure. Some of us thought that the infamous “loyalty oath” from which questions 27 and 28 were taken was administered only to draft age men; others thought that all adults had to fill out this questionnaire; some had relatives or family members who said that their entire family had to decide how to answer those questions.

It turns out that there was more than one questionnaire, and they were to serve two very different purposes: One was to determine who would be eligible to get out of the camps for work and school in the interior of the United States, and the other was indeed to determine who could be drafted into a segregated unit. The WRA and the Army had their own needs and there was infighting amongst government officials about the administration of these questions, as some feared that determining who was “loyal” and who was not attacked their own argument that all Japanese and Japanese Americans had to be placed in concentration camps in the first place because the basis of that decision was that it was IMPOSSIBLE to tell who was “loyal”. In other words, a loyalty oath would expose the big lie that made the internment camps “necessary” in the first place.

But I digress.

I’ve tried to solve the misnomer that lies in the title and in the very heart of the play by making distinctions within the dialogue to set the record straight, but we’ll have to see if that’s enough. Meanwhile, the private reading, which was done solely for my benefit to see what was working and not working in this adaptation, taught us a number of valuable things, and one of them wasn’t directly related to drama: Those of us who’ve been doing Asian American theatre for the past 30 plus years may think we already know all this stuff already, but we really don’t. In my play THE MIKADO PROJECT (co-written with Doris Baizley), there’s a running gag in which the actors chant “No more Camp plays ever” (there’s also a gag about “NO NO BOY: The Musical” which I’m now beginning to think is not such an absurd idea, but don’t worry, that’s NOT what we’re going to do here) which came from an old feeling common to both East West Players and the Asian American Theater Company in the 1980s that that particular subject had been exhausted. But this book – not a Camp book, not really – is full of characters never seen on any stage I’ve seen. Angry, self-destructive, self-loathing, they lose themselves in sex and booze, wondering if they’ll ever find the America that was once promised to them. Ironically, their nihilism is part of what makes them so vividly alive, proving that young people are the same in every generation – there exists in every generation an entire spectrum of feeling, and the darker hues of Ichiro, Freddie, Emi, and Kenji are ones not often seen in literature about the Nisei.

There are other problems as well – some of them more typical of adapting a story from one medium to another; for instance, the book, written in the first person, takes place mostly in the introspective Ichiro’s mind. Some of the best prose consists of his thoughts which often don’t translate easily to dialogue. The book also ends on a plunge into despair, an existential cri de coeur that I suspect works far better in fiction than it might on the stage, where audiences usually desire, if not require, some sense of resolution. In this case, knowing what we know now, I think it’s possible to end this play on a note of hope, rather than despair, as we do know that most of these people did, in fact, find a way to live, that Japanese Americans for the most part, found some piece of the American Dream. But making changes is the other scary part about adapting a well-known book to which people have an emotional connection: How much change is sacrilege? How much change constitutes a desecration?

I suspect people will let us know.

The play is still in development – we are planning a public reading at the Center for the Preservation of Democracy on Saturday, October 31, which will probably lead to further changes. The first draft of this adaptation stayed as true as I could make it to the original; I compressed some characters and left out scenes which were either too hard to stage or that I felt were dramatically unnecessary, and some of the structure was slightly re-ordered, but after a reading in our living room, the response from the artists involved was unanimous: Take more liberties with the story to make it more stage worthy.

I’ve done that with each succeeding draft, inventing more dialogue, and extending one small element into an ongoing theme, and building a new ending made up of dialogue from throughout the book to create a sense of epiphany – everything that Ichiro has heard up to this point finally adds up to something more than despair. I believe what is evolving is true to the spirit and intent of the work, and I believe lovers of the book will not feel betrayed by the differences in this adaptation, but the proof of the pudding will be in the eating.

Come out to the reading on October 25, 2009 at 2pm at the Miles Memorial Auditorium in Santa Monica, part of the Breaking the Bow Festival, and October 31, 2009 at the Center for the Preservation of Democracy, Los Angeles. Then come back for the world premiere production in the spring of 2010 and let us know what you think.

For more information, you can email us at: nonoboy2010@gmail.com

© 2009 Ken Narasaki