>> Part 1

The Nishizu family’s story of “relocation” and “resettlement” is only one among thousands of parallel versions involving other Japanese American mainlanders—truly a “people in motion”—during the World War II era. It is of particular value, however, because it spotlights and invites strategic exploration of a largely neglected aspect of Japanese American history, society, and culture: the prewar, wartime, and postwar circumstances of Nikkei communities within what historians Eric Walz and Andrew Russell have styled the Interior West of Japanese America.1 This essay will examine this topic in some depth, placing special emphasis upon the enduring historical experience of Japanese Americans living in the states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah.2 By exploring these lesser-known stories, we achieve a broader and more multidimensional understanding of the Japanese American experience as a whole and give a voice to those communities that have always existed but have often been pushed to the margins in accounts of the more mainstream West Coast Japanese American communities.

In addition to touching upon the five states mentioned above, the Nishizu narrative mentions three other western interior states: Idaho, Nevada, and Wyoming. These eight states—as well as Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and South Dakota—can be perceived in the present context as constituting the Interior West region. (This categorization is useful despite the fact that these states range over a number of variably designated geographical subregions: Pacific Northwest, Southwest, Intermountain, Great Plains, and Midwest.)

One notable commonality between these fourteen states is their relatively large geographical size. This point is dramatized by their rankings in total area among the 50 U.S. states.3 These states also are alike in that they have comparatively small total populations.4 Another common denominator for the 14 Interior West states is their comparatively small Asian American population relative to the national average of 3.6 percent (according to the 2000 U.S. census).5 In terms of the racial-ethnic population (Asian/Black/American Indian/Hispanic) of the Interior West, however, it is apparent that a noticeable disparity in this regard exists between the five principal states and the nine subsidiary states when the percentages for the two units are compared to the national average percentage of 29.3.6

When Clarence Nishizu and his party explored resettlement possibilities in the Interior West in early 1942, the demographic profile for the area’s 14 states (based on 1940 census information and arrayed in alphabetical order) reveals the following total and racial-ethnic population figures: Arizona (499,261 - 174,371); Colorado (1,123,296 - 109,343); Idaho (524,873 - 8,300); Kansas (1,801,028 - 79,571); Montana (559,456 - 21,228); Nebraska (1,315,834 - 23,705); Nevada (110,247 - 9,263); New Mexico (531,818 - 261,387); North Dakota (641,935 - 10,791); Oklahoma (2,336,434 - 232,629); South Dakota (642,961 - 24,206); Texas (6,414,824 - 1,663,712); Utah (550,310 - 9,962); Wyoming (250,742 - 10,273).7 As for the Interior West Nikkei population at the point of the U.S. entry into World War II, it was distributed as follows: Arizona (632); Colorado (2,734); Idaho (1,200); Kansas (19); Montana (508), Nebraska (480); Nevada (470); New Mexico (186); North Dakota (83); Oklahoma (57); South Dakota (19); Texas (458); Utah (2,210); and Wyoming (643). Even in 1940, all fourteen Interior West states could claim enduring communities, however modest, of Nikkei living and working within their boundaries.8 In 1900 there were a total of 5,278 Japanese Americans living in the 14 Interior West states, with 767 of them residing in the primary five states and 4,509 in the supplementary nine states. By 1940, the total number of Nikkei in the Interior West had grown to 9,624—however, their distribution in the primary and supplementary states had almost reversed itself: the five primary states now counted 6,220 as opposed to the nine states’ 3,404 Nikkei. What accounts for this transformed situation?

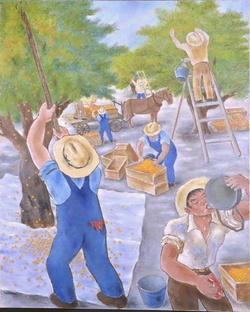

Japanese laborers working on apricot farm. Henry Sugimoto Collection. Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa. Japanese American National Museum. (92.97.110)

The work of the late Nisei historian Masakazu Iwata—in particular, his book Planted in Good Soil: A History of the Issei in United States Agriculture —is especially helpful in explaining the population numbers above. Because Iwata’s focus is on Japanese immigrants who came to the U.S. mainland after 1884 when Japan began allowing general emigration of laborers to foreign countries, he only alludes to the 61,111 Japanese who were living in the Hawaiian Islands by 1900, by and large toiling on the many sugar plantations there. For Iwata, what is notable is that between 1902 and 1907 37,000 Japanese migrated to the continental U.S., where they joined the 80,000 who had arrived directly on the mainland between 1893 and 1910; these numbers were augmented by thousands of their fellow countrymen who indirectly entered the U.S., legally and illegally, from Canada and Mexico).

Whether journeying directly to the U.S. mainland or via Hawai’i, most Japanese immigrants landed at the West Coast ports of Seattle and San Francisco. While some people settled proximate to these cities, many more fanned out to other parts of the West. “In contrast to the westward migration across the American continent of immigrants from Europe after their landing in Atlantic coast ports,” observes Iwata, “those from Japan pushed eastward from the Pacific Coast, their progress generally coming to a halt roughly at the Missouri River in the Nebraska sector, [while] in the south the farthest advance eastward was into the Rio Grande Valley of Texas.”

These overwhelmingly unmarried male Issei were drawn to the U.S. primarily for economic reasons. Most came from agrarian backgrounds in southern Japan and—despite the fact that they were preponderantly common laborers—most were relatively well-educated. As compared to those in this immigrant wave with a sojourner mentality (i.e., who determined to stay abroad only long enough to earn sufficient money to alleviate their Japanese families’ dire financial straits and/or to build lives for themselves in Japan), there was only a very small number who intended to settle permanently in America.

Fortuitously, the Issei arrived in the U.S. as the Interior West region was experiencing what historian Eric Walz has described as “an economic boom fueled by railroad construction, coal and hard-rock mining, and agricultural development.” Recruited by labor contractors, the Issei were a mobile workforce. As both individuals and gang laborers, they moved not only between different work opportunities on the Pacific Coast and the western interior sections of the U.S., but also between America and Japan and many other parts of the world in which Japanese workers filled a variety of employment needs. Concurrently, their emigration patterns relieved population pressure on their native Japan, and through remittances, increased its wealth.

Many Issei who came to America first found employment with the steam railroad companies in two of the five primary Interior West states, Colorado and Utah, but many more also worked for the railroad industry in such secondary states as Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Nevada. This largely accounts for why the 1900 census counted so many more Nikkei in the secondary states rather than the primary states. However, as Iwata notes, even though they achieved remarkable success—supplanting Chinese railroad workers; gaining wage parity with (and then employer preference over) other immigrant laborers from such countries as Italy, Greece, and Austria; improving their status within the industry by becoming section workers (occasionally even foremen) and office secretaries and interpreters; and accumulating some surplus capital—the majority of Issei “began to look about for work other than that in the railroads.” Nonetheless, as Masakazu Iwata is quick to remind us, in spite of this exodus of Issei workers from the railroads during the first decade of the twentieth century, “even as late as 1930 there were over 2,000 Japanese still working in the railroad industry.” Moreover, as historian Andrew Russell has more recently indicated, “while their numbers shrank steadily in the prewar [World War II years], the Nikkei of the railroads and mines continued to account for a sizable percentage of the Japanese-American population of most interior states right up to the start of the war.”

Russell recounts that sometime after going into railroad work, Issei entered into mining operations (albeit to a far lesser extent). While there were outcroppings of Japanese mining settlements in Rock Springs and other southern Wyoming towns in the late 1890s, most Japanese immigrants did not labor in coal and copper mining camps until the first decade of the twentieth century. “The first Japanese coal miners in Utah,” surmises Russell, “probably arrived in 1904, when 145 hired on at the Castle Gate Mine in Carbon County . . . [and] around this time, coal mining companies in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico also began to employ significant numbers of Japanese miners.

It is the opinion of Masakazu Iwata that Japanese working in the coal mines of Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah experienced harsher treatment than did Issei laborers in the coal mining industry within Wyoming, where they were more numerous than in the other three states. Although Issei miners in Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah avoided wage discrimination and were paid roughly the same as other immigrant groups, they typically were disallowed union membership and were consigned to live in a “Jap Town” outside of the boundaries of a given community settlement; they were also regarded by other races and ethnic groups to be in the same category as blacks. Wyoming—which in 1909 was home for over 13 percent of the total 7,000 Japanese living in the Interior West region—permitted Nikkei (and Chinese) to become members of the United Mine Workers, and this development led to a shortened work day and higher wages for Asian workers compared to their counterparts elsewhere in the region.

Coal Delivery. Jack Iwata Collection. Gift of Jack and Peggy Iwata. Japanese American National Museum. (93.102.30)

Barbara Hickman, a historian of the Nikkei experience in Wyoming, has observed that by 1909 the Issei residents of that state were increasingly finding the conditions of railroad and mining life too harsh. At the same time, they began to shift their goals: rather than continue to live in deprivation in order to save money and then return to Japan, they sought to become permanent settlers in America. “For those who stayed in the U.S.,” writes Hickman, “savings went towards the establishment of small businesses and family farms. Issei, for the most part, quit the perilous railroad and mining industries by 1910 and [thereafter steadily] moved away from the state of Wyoming.”

In her work, Hickman seeks to rectify the fact that historians of Wyoming history have tended to restrict their treatment of the Japanese experience in the so-called “Equality State” to their World War II incarceration at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center (whose peak population reached 10,767); the camp was located in the northwest corner of the state between the small communities of Powell and Cody. Wyoming’s population of people of Japanese ancestry did decline from a 1910 figure of 1,596 (1.09 percent of the state’s total population of 145,965) to 1,194 in 1920 and 1,026 in 1930, dropping somewhat precipitously to 643 in 1940. Despite these falling numbers, Hickman does not feel that this justifies the fact that “the Japanese [have] quietly disappeared” from Wyoming’s historical record. To make her point, she not only references the existence of pre-1910 communities in Wyoming with a considerable population of Issei, but also documents those towns—such as Rock Springs in south central Wyoming— that boasted nihonmachi (Japantowns).

Montana shares Wyoming’s historical experience of having had a sizeable Nikkei population at the outset of the twentieth century that thereafter dwindled in the decades prior to World War II. In 1900 Montana’s Japanese population was 2,441, which then spiraled downward: 1,585 in 1910, 1,074 in 1920, 753 in 1930, and 508 in 1940; this drop was even more dramatic than the Nikkei population numbers in Wyoming. During World War II, the U.S. Department of Justice operated the Fort Missoula Internment Camp for enemy alien Italians and roughly 1,000 Japanese internees. Unfortunately, the camp’s existence and its place within the context of Japanese America’s defining event—wartime exclusion and detention—has seemingly overshadowed all other facets of the Nikkei experience from Montana’s historical narrative and collective memory.

NOTES:

1. See, in particular, the following studies: Eric Walz, “Japanese Immigration and Community Building in the Interior West, 1812-1945” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 1998) ; “From Kumamoto to Idaho: The Influence of Japanese Immigrants on the Agricultural Development of the Interior West,” Agricultural History 74 (Spring 2000): 404-18; “Japanese Settlement in the Intermountain West, 1882-1946,” in Mike Mackey, ed., Guilty by Association: Essays on Japanese Settlement, Internment, and Relocation in the Rocky Mountain West (Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 2001), pp. 1-24; and Andrew Benjamin Russell, “American Dreams Derailed: Japanese Railroad and Mine Communities of the Interior West” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2003). In the second of the three citations above, Walz offers a precise definition of the Interior West: “that part of the United States east of Washington, Oregon, and California and west of the Missouri River” (p. 404). In addition to these writings by Walz and Russell, see a relevant new study by Kara Allison Schubert Carroll, “Coming to Grips with America: The Japanese American Experience in the Southwest” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2009).

2. My intention here is to avoid, as much as possible, replicating information about these five states that the Enduring Communities project state scholars—Karen Leong and Dan Killoren (Arizona); Daryl J. Maeda (Colorado); Andrew B. Russell (New Mexico); Thomas Walls (Texas); and Nancy J. Taniguchi (Utah)—have provided in their respective essays, which follow this one and are written from a multicultural perspective.

3. Rankings in terms of area: Texas (2); Montana (4); New Mexico (5); Arizona (6); Nevada (7); Colorado (8); Wyoming (10); Utah (13); Idaho (14); Kansas (15); Nebraska (16); South Dakota (17); North Dakota (19); Oklahoma (20)..

4. Rankings in terms of population size: Wyoming (50); North Dakota (47); South Dakota (46); Montana (44); Idaho (39); Nebraska (38); New Mexico (36); Nevada (35); Utah (34); Kansas (33); Oklahoma (27); Colorado (24); Arizona (20); Texas (2). The last three of these states (Colorado, Arizona, and Texas), observably, are exceptional in that their present-day population ranking falls within the upper half of the nation’s fifty states. However, viewed historically, only Texas claimed such a ranking in the six national censuses extending from 1910 to 1960: 1910 (5); 1920 (5); 1930 (5); 1940 (6); 1950 (6); 1960 (6). As for Arizona, its population rankings differed markedly, with a population loss from the early part of the twentieth century until 1960: 1910 (45); 1920 (45); 1930 (43); 1940 (43); 1950 (37); 1960 (35). Colorado’s ranking during this time period changed very little: 1910 (32); 1920 (32); 1930 (33); 1940 (33); 1950 (34); 1960 (33). When looked at another way, it can be appreciated that Colorado’s population increased by a robust 30.6 percent between 1990 and 2000, while Arizona’s grew by a whopping 40 percent.

5. This is certainly true of the five principal states: Arizona (1.8 percent); Colorado (2.2 percent); New Mexico (1.1 percent); Texas (2.7 percent); and Utah (1.7 percent). But this point applies (with one obvious exception) even more powerfully to the nine other states: North Dakota (0.6 percent); South Dakota (0.6 percent); Nebraska (1.3 percent); Nevada (4.5 percent); Kansas (1.7 percent); Oklahoma (1.4 percent); Wyoming (0.6 percent); Montana (0.5 percent); and Idaho (0.9 percent).

6. On the one hand, all but Nevada (32.3) of the latter states fall beneath this percentage (and most substantially so): North Dakota (6.3 percent); South Dakota (10.9 percent); Nebraska (11.7 percent); Kansas (15.3 percent); Oklahoma (20.1 percent); Wyoming (10.1 percent); Montana (9.0 percent); Idaho (10.6 percent). On the other hand, three of the five former states exceed (two quite strikingly) the national average percentage: Arizona (35.2 percent); Colorado (24.1 percent); New Mexico (54.6 percent); Texas (46.0 percent); Utah (12.8 percent).

7. Because the primary focus in this essay is on the five states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah, the statistics for these states are rendered in bold type.

8. For example, in 1900, at the twentieth century’s outset, the five primary states had these Japanese American populations: Arizona (281); Colorado (48); New Mexico (8); Texas (13); Utah (417). In the three decennial censuses between 1900 and 1940, the almost universally escalating number of Nikkei in these states is captured statistically: Arizona (371 - 550 - 879); Colorado (2,300 - 2,464 - 3,213); New Mexico (258 - 251 - 249); Texas (340 - 449 - 519); Utah (2,100 - 2,936 - 3,269). As for the subsidiary nine states, their Nikkei decade-by-decade populations—recorded in the four U.S. censuses for those decades—from 1900 through 1930 were characterized by a generally fluctuating growth pattern: Idaho (1,291 - 1,263 - 1,569 - 1,421); Kansas (4 - 107 - 52 - 37); Montana (2,441 - 1,585 - 1,074 - 753); Nebraska (3 - 590 - 804 - 674); Nevada (228 - 864 - 754 - 608); North Dakota (148 - 59 - 72 - 91); Oklahoma (0 - 48 - 67 - 104); South Dakota (1 - 42 - 38 - 19); Wyoming (393 - 1,596 - 1,194 - 1,026).

© 2009 Arthur A. Hansen